“The coastal ecosystems and coastal jobs are critically important for the economy of the state. That’s everything from seafood production to ecotourism to port activities.”

– Clark Alexander, director, Skidaway Institute of Oceanography

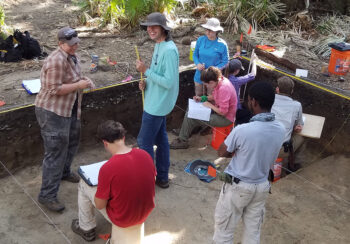

Photo by Stephen Morton

Losing ground?

For the majority of Georgia’s population, the coast is a place to come and have fun temporarily, to visit the sites and do a little fishing, shopping and beach-combing, before they go back home. But the people who live there depend on the coast’s resilience.

“The coastal ecosystems and coastal jobs are critically important for the economy of the state. That’s everything from seafood production to ecotourism to port activities,” said Clark Alexander, director of UGA’s Skidaway Institute of Oceanography.

The state’s seafood industry employs nearly 10,000 people, to the tune of $1.4 billion in sales, while the recreational fishing industry supports more than 1,400 jobs with another $140 million in sales. Because many of the species in these two industries spend at least part of their life cycles in the marsh, Alexander said, it’s vital for business that coastal ecosystems stay healthy.

“Georgia has some of the best and most protected coastal ecosystems on the eastern seaboard. It has 14 barrier islands, and most are in long-term conservation,” said Mark Risse, director of Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant and Georgia Power Professor of Water Policy.

One of the biggest questions on the coast is how marshes will respond to the ongoing rise in sea level. Will they be able to withstand the ascending waterline, or will the Atlantic wash them away? According to photographic studies from the air, it looks like the marshes have been able to replenish themselves at the same rate the sea rises—so far. But models show the water’s pace is likely to increase.

“When we look forward, it’s a little scarier because we see the pace of sea-level rise increasing, and it means the marsh has to keep up. It’s going to have to sort of run faster to stay in place,” explained Merryl Alber, director of the UGA Marine Institute on Sapelo Island.

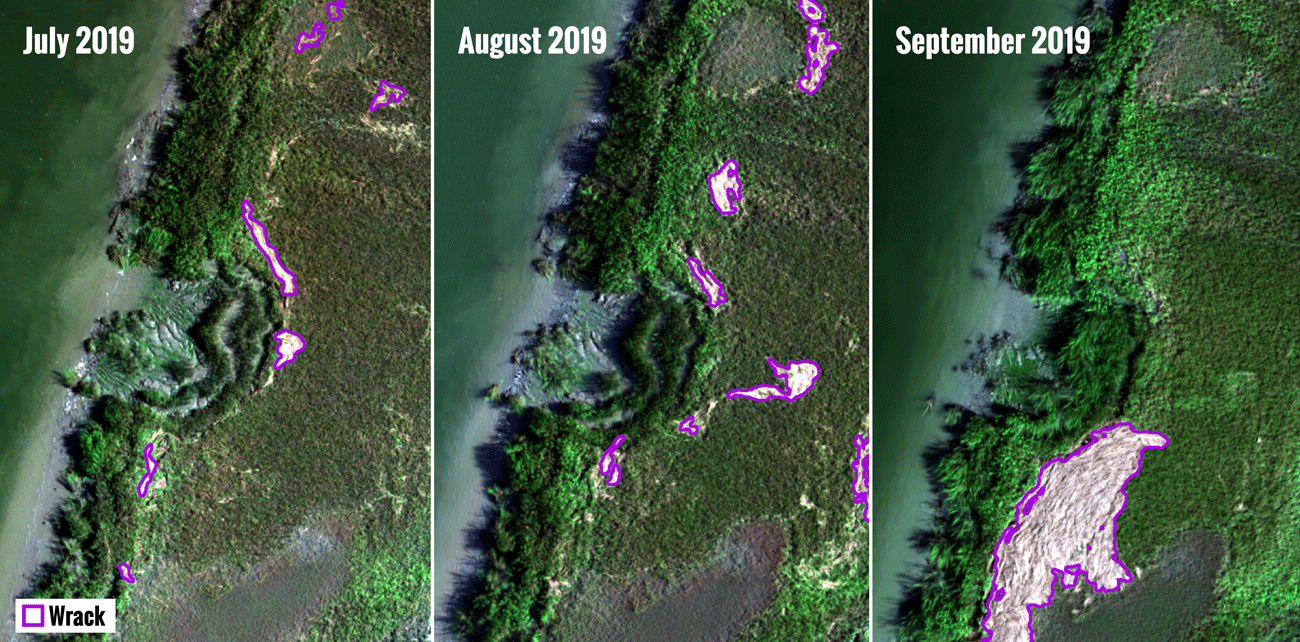

Alber is working with research scientist Jessica O’Connell on a study mapping what’s going on under the soil in the marshes.

“There’s evidence that we might be losing ground that we’re not seeing when we look from above,” said Alber. “That could lead to the loss of that marsh, which would result in less carbon being stored by the plants.”

If plants aren’t able to store as much carbon, it will stay in the air where it could contribute to higher temperatures. What’s more, marshes are a nursery of nutrients for developing plant and animal life. Take away the marshes, and you wipe out a good portion of the base of the food web of the coast.

In the midst of mapping this loss, they’re trying to see if they can identify the most vulnerable spots and share it with the Department of Natural Resources to protect those areas.

The resilience of a living shore

One way to help keep the coast resilient may be to convince developers to switch from using armored shorelines, made of metal, wood or concrete, to using natural materials like grasses, oyster shells, sand or rock in an array known as a “living shoreline.” Whereas armored shorelines simply keep the water at bay, sometimes just moving its destructive force down the coast, living shorelines can absorb the water.

“Living shorelines can adjust and regenerate after a hurricane or a major storm. It may look a little beat up, but it’s going to patch itself back together using solar energy,” said Brian Bledsoe, director of UGA’s Institute for Resilient Infrastructure Systems (IRIS). “How many bulkheads that get hammered do you see building themselves back up?”

These shorelines work by trapping sediment in the water, which promotes plant growth. They also can absorb much more of the incoming waves, with a small portion of marsh absorbing a large portion of the wave energy, explained Bledsoe.

The living shorelines also protect those species that are a critical part of the coastal ecosystem. Studies show an increase in fish, crabs and shrimp at living shorelines built by Marine Extension and Sea Grant on Tybee, Sapelo and Little St. Simons islands. Bagged oyster shells and native vegetation provided the base, with natural oyster reefs forming on top over time. In addition to erosion control, the oyster shells improved water quality by naturally filtering pollutants from runoff.

“Living shorelines in Georgia are doing the job they were designed to do and have remained intact after storm events and continue to stabilize the shoreline,” said Tom Bliss, director of Marine Extension’s Shellfish Research Lab. “Continued monitoring will allow us to determine their longevity.”

Bledsoe is working on teaching permitting agencies up and down the coast about the benefits of living shorelines, which can work in concert with armored shorelines for a hybrid approach, making the system stronger overall.

“If you go down to your permitting agency and you want to get a permit for a bulkhead, they have a standard process and can issue those relatively quickly. It’s something they’re familiar with,” said Bledsoe. “But if you want to build a living shoreline, they’re not as accustomed to handling that. It’s often outside their comfort zone.”

IRIS and Marine Extension collaborate with state and federal agencies, as well as private partners, to raise awareness of living shorelines as a prudent investment. IRIS has proposed a resiliency plan to the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation for the backside of Tybee Island, which would create living shorelines along with natural pathways to move floodwaters in a way that reduces damage to infrastructure.

It’s a critical time, according to Risse. As coastal communities like Tybee and St. Marys experience flooding during high tides, there’s a real concern that people’s homes and retirement nest eggs will be drowned. With the region expected to double in population over the next 40 years, helping communities understand the ongoing risk while creating sustainable development is one of its biggest challenges.

Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant for years has been working with coastal communities to join the Consumer Ratings System, a Federal Emergency Management Agency program that reduces flood insurance premiums—sometimes by as much as 80 percent—for property owners in cities and counties that take action to exceed minimum floodplain management standards.

Tybee Island put $1 million into drainage improvements and began requiring new property owners to build at least one foot above the base flood elevation. As of 2017, Tybee Island property owners had saved more than $3 million in insurance premiums.

The troubles with floods

In addition to flooding from the sea, overworked stormwater systems can inundate the streets as well. Because these systems are designed to drain to rivers or the ocean, high tide can bring an intrusion of saltwater. When it rains, the basins are already partially full, giving the streets nowhere to drain.

Crumbling septic systems are one potential risk, said Alexander. As sea level rises, the coastal water table is pushed up, reducing the amount of dry soil the system uses to filter the waste and making it easier for disease-bearing materials to potentially contaminate drinking water.

An inventory of septic systems in an 11-county region along the Georgia coast was completed by Marine Extension last year. Risse and Scott Pippin, a faculty member with UGA’s Carl Vinson Institute of Government, are now working with the individual counties to determine which systems may be at risk and adding them to a public database.

In partnership with IRIS, Pippin has funding from the National Atmospheric and Oceanic Administration to use this septic inventory to assess present and future vulnerabilities in Bryan County, west of Savannah. Bryan is one of Georgia’s fastest-growing counties.

Jill Gambill, Marine Extension’s coastal community resilience specialist, helps communities and coastal residents plan for future incursions of the sea. Following Hurricane Matthew, Gambill led a series of focus groups in coastal communities to assess residents’ attitudes and behaviors related to evacuation. Using this information, Gambill produced materials to help better prepare coastal residents in the event of a storm, rolling out a YouTube video, social media and graphics to encourage residents to evacuate in advance of Hurricane Irma in 2017.

“One of the biggest take-homes is that storm surge is complex and there are lots of aspects to it,” Risse said. “We need to do a better job communicating what the risks are.”

Environmental justice for all

Taking practical steps is very much influenced by one’s economic means, explained Alber. “One thing people are starting to key into is understanding the differences in people’s ability to respond to the challenges,” she said. “If you have more money and live in a flooded area, you can probably move. But if you don’t have a lot of money, it may be challenging. So there are some environmental justice questions.”

The identity and economic class of a community can have a significant effect on how much help and access they get to these solutions, said Nik Heynen, professor in the Department of Geography.

As part of UGA’s Cornelia Walker Bailey Program on Land and Agriculture, co-directed by Heynen and Sapelo Island business leader Maurice Bailey, Heynen spends a lot of time working with the island’s Gullah Geechee community of Hog Hammock. These direct descendants of people brought over as slaves from West Africa possess a unique culture. The community was once as large as 500 people but has dwindled to around 40. It’s a relationship that took a lot of time and care to build, Heynen said.

“Stripping assumptions about what people in the community want, opening lines of communications between people who respect each other and are willing to be honest, even when it’s difficult, goes a long way,” he said.

Heynen works alongside residents as they reintroduce several crops, like sugar cane, that were once grown on the island. Currently, with five plots of land, one as large as 25 acres, they’re working it on a shoestring, using a lot more manual than mechanized labor.

“If we can get a tractor, it’ll really be a game-changer,” said Heynen.

Teaching the future

In Savannah, UGA’s Marine Education Center and Aquarium, part of Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant, hosts kids aged 6 to 15 during the Summer Marine Science Camp and provides educational field trips to students during the school year, where they learn from scientists about the coastal ecosystem, sea life and local habitats. The aquarium also conducts adult education programs. Its offerings are designed around the concept that educating and familiarizing the public with the ecosystem will inspire people to preserve and protect their environment.

In addition, Marine Extension hosts internship programs for students, teachers and the public in topics such as aquarium science, water quality, shellfish, coastal septics and socioeconomic issues. College students take part in courses where they learn about and prepare for careers in the marine sciences and coastal management.

To help teach residents about the dangers of staying in place during an evacuation order, Sun Joo (Grace) Ahn, associate professor in the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication and director of the Games and Virtual Environments Lab, has created a virtual reality system that gives them a first-person experience of a hurricane.

“Virtual reality is particularly good at placing users in a situation that can be potentially fatal or even impossible in the physical world, in a way that’s very realistic to the senses,” said Ahn.

By experiencing a storm in a virtual world, Ahn is giving people a way to see just how dangerous a storm can be. Users can look in all directions and see the water entering a house and surrounding them with debris, mud and furniture, making it difficult for them to move, much less leave. At the end, the simulation shows what someone should do in such a situation.

“It’s a very visceral, frightening experience,” said Ahn.

Living through a hurricane can be terrifying. Sun Joo “Grace” Ahn, who directs UGA’s Games and Virtual Environments Lab, created a virtual reality simulation that shows users what it’s like to experience a hurricane storm surge in real time. “It’s a very visceral, frightening experience,” Ahn says.

The big picture

“One third of the salt marsh in the eastern United States is along our 100 mile coast and these marshes have a tremendous impact on the entire Atlantic ocean,” Risse said. “Key parts of our coastal food web including many fish and sea turtles originate in coastal Georgia and travel around the world.”

To that biodiversity, add the cultural diversity of those who call the Georgia coast home, from the Gullah Geechee and descendants of the European settlers, to the newcomers arriving from the four corners of the globe, and it’s clear that the coast is a lot more complex than previously understood. It takes patience, the ability to learn from what each other sees, and an openness to new ideas to fully comprehend how the natural world responds to the activities of humankind. One thing is sure: We’ll get a lot farther working the puzzle together than on our own.

That goes for scientists too.

“You have to learn your colleagues’ thought structures, their tools, models, how they view the world,” said Bledsoe. But it gives researchers a more holistic view of the region, so they can understand how everything works together. “It takes a lot of time, discussions and humility.”

The R/V Georgia Bulldog is the oldest research vessel operated by Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant. First dubbed the Lady Marilyn when she was built in 1977, the Bulldog today conducts a wide range of basic and applied research, such as sea turtle ecology and techniques that could be helpful to Georgia’s fisheries and shrimpers. (Photo by Peter Frey)