More than 4,500 years ago, scattered communities began to appear on barrier islands along the southeastern coastlines of the North American continent. Characterized by their reliance on a diet of mollusks and fish, these coastal villages have been identified by the large collections of shells they left behind—sometimes in mounds and heaps of food remains, sometimes in rings that encircled their villages.

Archaeologists have hypothesized that these villages were abruptly abandoned due to a sudden shift in climate. But new research from the University of Georgia Laboratory of Archaeology indicates that environmental change was happening both during the settlement of these island villages and—over centuries longer than previously believed—during their gradual decline. Moreover, the evidence shows that the Native Americans who lived in those villages showed considerable resilience in adapting to the changes around them.

In a paper published on PLOS ONE, UGA archaeologists Carey Garland and Victor Thompson (along with several co-authors) describe using multiple methodologies to show that climate change was occurring along the Georgia coastline in the years from 4,500 to 3,800 before present (BP). These changes affected the size and availability of the marine creatures that provided sustenance to the island culture, which then resulted in the abandonment of former villages for areas of the coast not previously settled.

“We’re not just looking at climate—we’re looking at the interaction between the environment and the people, and how they adapted to this,” said postdoctoral researcher Garland. “It was originally thought that people abandoned these shell rings because of climate instability, but our findings show that there was climate instability the whole time they were occupied.”

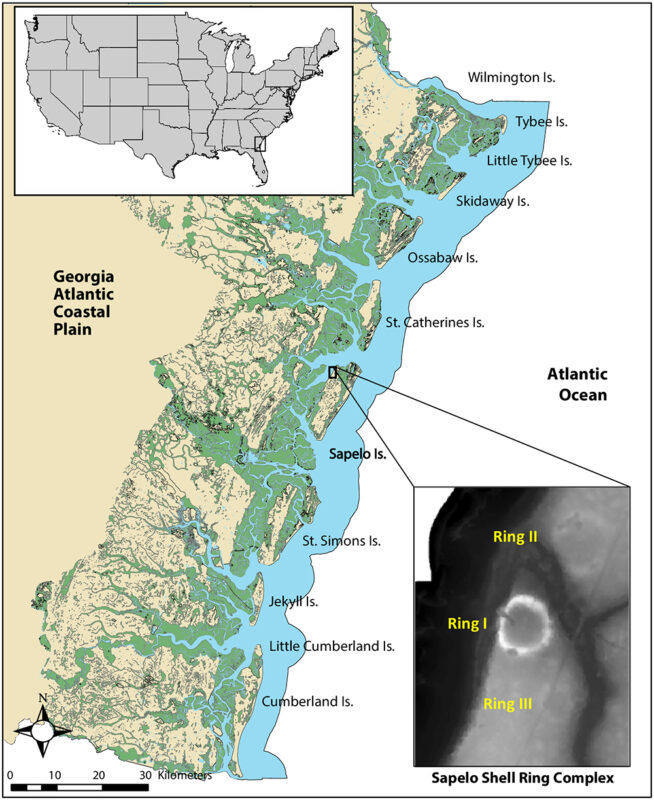

The study focused on the Sapelo Shell Ring Complex, a group of three shell-ring villages on Sapelo Island, about 70 miles south of Savannah, Georgia. The first and largest of these villages, with an encircled area of about 6,000 square meters, was founded around 4,250 BP. Occupation of the three villages overlapped, and the third and smallest ring appears to have been abandoned by 3,755 BP.

Over those 500 years, the Native American inhabitants were forced to deal with falling sea and salinity levels in the coastal estuaries that served as their prime fishing grounds. These environmental conditions reduced the size and number of the oysters and other fish and mollusks that served as one of the villagers’ main food sources (these cultures predate the use of agriculture along the southeastern coast).

“If the sea level drops and there’s no fresh water and no fish, you can’t live there—but where do you go? How do you respond?” said Victor Thompson, Distinguished Research Professor and director of the Laboratory of Archaeology. “As archaeologists, we try not to oversimplify the explanation. ‘Sea level dropped, and that’s what caused the abandonment’—that’s a convenient narrative. But it’s much more complicated than that.”

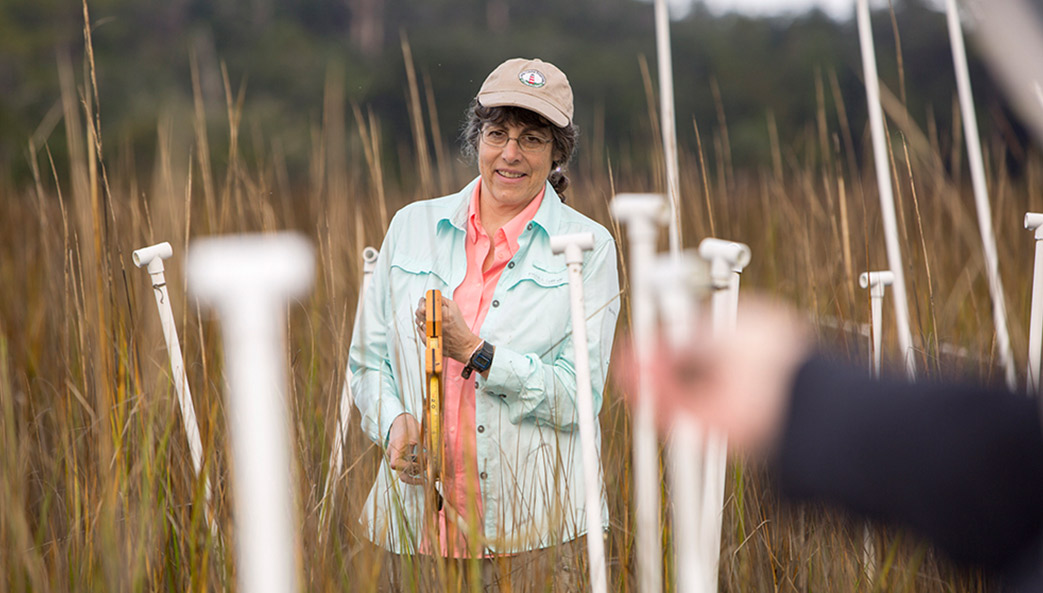

To arrive at their conclusions, the researchers pulled together evidence from radiocarbon dating of organic materials found in the Sapelo complex, such as nut fragments, deer bone, pottery sherds and carbonized wood; from measuring the size and oxygen isotope levels of oyster shells sampled from all three ring villages; and from tree ring analysis, or dendrochronology, that confirmed the environmental fluctuations during the period in question.

These analyses helped confirm the overlapping periods of occupation among the three rings, as well as the shrinking size of oysters from 4,300 to 3,800 BP. While shrinking shell size also could be due to overharvesting rather than environmental change, the researchers consider this unlikely.

“Native Americans sustainably harvested oysters for thousands of years, so it doesn’t make sense to have this one period where human activity caused reduction in shell size,” Garland said. “Also, if you contextualize it with the isotope data showing there was a reduction in salinity, it is more likely that the reduction in shell size is due to environmental causes.”

Thompson said the new evidence depicts Native Americans as more adaptive than simpler explanations give them credit for.

“We do indeed have a lot of environmental fluctuation going on and it gets rough, but these communities persist,” he said. “They still do what we might call the work of community, of being together rather than breaking apart. They’re still resilient.”

The new study’s findings also support Native American oral history. Georgia, including Sapelo Island, is part of the traditional homelands of the Muscogee Nation. As Legus Perryman, principal chief of the Muscogee from 1875–1895, recounted: “Then they traveled on again eastward until they came to the ocean (‘big water’). They found that the water of the ocean would come up and go out, enabling them to collect oysters and other things good to eat, and they stopped there and lived on those products, being unable to pass beyond.”

This research was supported in part by Georgia Coastal Ecosystems, a Long-Term Ecological Research Project funded by the National Science Foundation.