Dr. José Cordero regularly flies from Georgia to Puerto Rico to check on expectant moms who are at great risk from the Zika virus that has spread rapidly throughout tropical regions of the world, especially the Western Hemisphere.

In the mainland U.S., approximately 5,000 Zika virus disease cases were reported to health officials from January 2015 through mid-March 2017. Of these, 223 were acquired locally.

In comparison, there were almost 40,000 Zika virus disease cases reported in Puerto Rico in that time period. All but 137 were acquired in Puerto Rico.

Cordero, UGA’s Patel Distinguished Professor in Public Health, was already part of a research team conducting an National Institutes of Health-funded study of preterm births at a clinic in Puerto Rico, called the PROTECT Center, when the Zika outbreak began on that island in January 2016. Now, the PROTECT Center—a consortium of UGA, Northeastern University, University of Michigan and University of Puerto Rico—has also become a focus in the care of would-be mothers and prevention of the disease, which can cause microcephaly, other serious birth defects and life-long developmental problems in newborns.

“We were in the right place at the right time when Zika emerged,” Cordero said.

The NIH asked the PROTECT Center to recruit more women early in their pregnancies. So far, the center has brought in nearly 100 women, each of whom is tested for Zika every month, in hopes of detecting the disease early. Pregnant women are especially at risk if bitten by a mosquito carrying Zika virus because it can affect the fetus.

Currently, there is no cure or vaccine for Zika. UGA researchers from the College of Public Health, College of Veterinary Medicine, College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, Franklin College of Arts and Sciences and Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication are working on different aspects of the disease, from gaining a better understanding of how the disease affects humans to creating a vaccine and understanding the barriers to its acceptance.

“We have a good team of people with expertise in various fields,” said Biao He, a Georgia Research Alliance Distinguished Investigator and the Fred C. Davison Distinguished University Chair in Veterinary Medicine. “What really bodes well is the investment the university and the state of Georgia have made in developing the field of infectious disease research,” added He, one of 14 members of UGA’s Zika working group.

“There was really a concerted effort to broaden and deepen the research into infectious diseases in the past few years.”

Stopping the spread

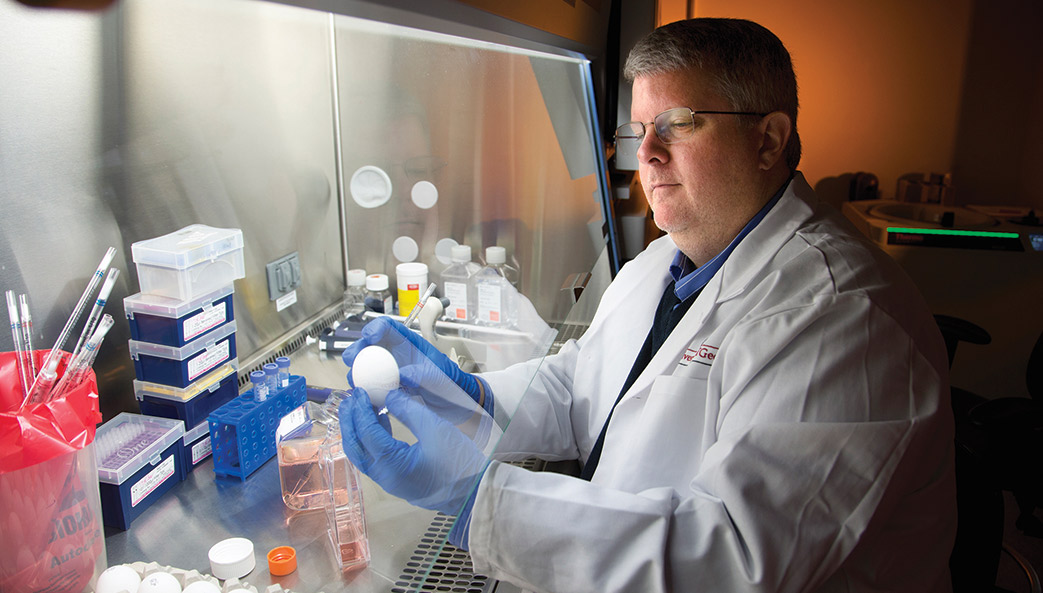

Ted Ross, Georgia Research Alliance Eminent Scholar in Infectious Diseases, has a collaborative research agreement with GeoVax Labs Inc. to develop a vaccine to prevent Zika. His laboratory in the Center for Vaccines and Immunology is using a non-infectious virus-like particle to prompt the body to mount a protective response to the pathogen without introducing any risk of actual infection.

This particle “stimulates the host’s immune system to respond to the vaccine as if it were the virus,” Ross said. This immune response, he explained, “leaves memory cells behind that can react in the future with antibodies to block the real Zika virus.”

Professor He is developing his own vaccine for Zika to use with a patented delivery system. In February 2017, tests of this vaccine in mice yielded “very encouraging results,” according to He. The next step, He said, is to test the vaccine further in animals—adding that if all goes well, human testing could begin soon.

But developing an effective protection against Zika in the lab is only part of the challenge. “The fact that something is a major breakthrough doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s going to be welcomed and readily embraced by consumers,” cautioned Glen Nowak, director of the Center for Health & Risk Communication at the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication.

Nowak’s new research, supported with funding from an interagency agreement between UGA and the National Vaccine Program Office, suggests that the public is not clamoring for a Zika vaccine. Only about one third of Americans would be willing to be vaccinated for Zika if public health officials recommended it for them, his research found.

Consumers often are reluctant to accept new vaccines, sometimes because of safety and effectiveness concerns, but Zika presents additional challenges.

“For a new vaccine, especially for something like Zika, if you don’t perceive yourself as being at risk for being bitten by a mosquito carrying Zika, you’re not going to be as interested in the vaccine,” Nowak said. “Compounding the challenge for a Zika vaccine is that for the vast majority of people, the data show that four out of five will not have notable symptoms, and for the people who do, the typical symptoms—such as soreness in limbs and fever—are short-lasting and don’t cause lasting harm.”

But the rise of Zika in the U.S., along with the possible spread of other tropical diseases such as chikungunya and dengue, may well shake that complacency.

“Mosquitoes are coming to you,” said Professor He. “That’s the undeniable fact. Tropical diseases are coming our way.”

Identifying the defects

Cordero and the research team at the PROTECT Center seek to answer a range of questions that are crucial to addressing the Zika threat, such as: What is the risk of infection? How high is the risk of infection in a pregnant woman compared to a non-pregnant woman? If the mother gets infected, what is the risk for the baby?

Another key issue is how to confirm whether a pregnant mother has the infection.

“For Zika, that’s a very important question because most people who get infected have no symptoms whatsoever,” Cordero said. “That’s OK for an adult who is healthy, but for a pregnant woman that may mean they could be exposing their baby to having serious birth defects, and they don’t know it.”

The center also is researching babies in their first year of life who were born healthy but could still be vulnerable to the disease if bitten by a Zika-carrying mosquito.

Even babies who don’t appear to be infected at birth might have issues that emerge in their first few years, Cordero said.

The clinic hopes to follow the babies for their first two years and longer, depending on funding.

“What we plan to do with the study is identify the birth defects early but also follow the children and find out not only if they have a brain abnormality, a small head, but other birth defects that may be linked to how the virus attacks nervous tissue,” Cordero said.

Microcephaly—the condition when a baby’s head is smaller than normal—is often associated with seizures, epilepsy and problems with swallowing and coordination.

The damage that Zika causes can go beyond microcephaly, according to research published late last year in the journal Development by a team of UGA scientists.

“Our study is the first to report a post-natal mouse model Zika virus infection in a developing brain,” said Jianfu Chen, an assistant professor of genetics.

“People think microcephaly is caused by violent disruption of the neural progenitor cells in the brain, but we found that there’s more than that,” Chen explained. “There’s extensive brain damage suggested by this massive neuronal death and vascular disruption in the developing brain.”

Examining the source

Thousands of mosquitoes awaiting infection with Zika are tucked away in a secure area of a lab in UGA’s department of infectious diseases in the College of Veterinary Medicine. Different kinds of plastic containers hold the mosquitoes depending on their stage of life. Larvae are developing in tubs of water. Mature mosquitoes have the freedom to fly in cages covered with mesh netting.

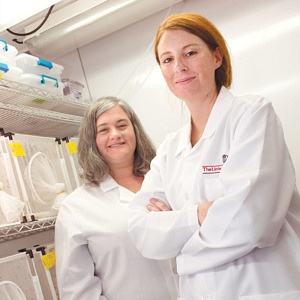

Among those are mosquitoes from Mexico that assistant professors Courtney Murdock, a mosquito ecologist, and Melinda Brindley, a virologist, are studying. Their research on how temperature and climate affect the transmission of vector-borne infectious diseases such as Zika started in 2016 with a National Science Foundation Rapid Response award.

Murdock and Brindley are attempting to find out how mosquito susceptibility to Zika infection, as well as the rate at which the virus replicates within the mosquito, are affected by exposure to varying levels of virus when mosquitoes feed on humans and variation in temperature and other environmental conditions.

“If we want to be able to predict what parts of the year, and what geographic spaces or regions might be suitable for Zika transmission, it’s important to characterize how the virus will respond to temperature and other environmental variables,” Murdock said.

These data will enable researchers and public health officials to “redefine where Zika will most likely become a problem in the U.S.,” Brindley added.

The pair plan to explore developing a new model that uses their data, along with socio-demographic and economic information, to predict human exposure and transmission risk.

John Drake, Distinguished Research Professor in the Odum School of Ecology and director of UGA’s Center for the Ecology of Infectious Diseases, is looking into a systematic and consistent way to collect the information needed for infectious disease intelligence and to anticipate and respond to emerging outbreaks. Developing models is an important part of creating an early warning infrastructure, said Drake, who is collaborating with Murdock and Brindley.

The outbreaks of Zika—and their tragic human cost—“ups the ante in terms of how important it is for us to understand the biology and the epidemiology of these diseases,” Drake said.