What does it take to become a Guggenheim fellow? A big idea. Boldness coupled with humility. A keen awareness of just how much time the project will require. And an unwavering curiosity about what it means to be a citizen of our world.

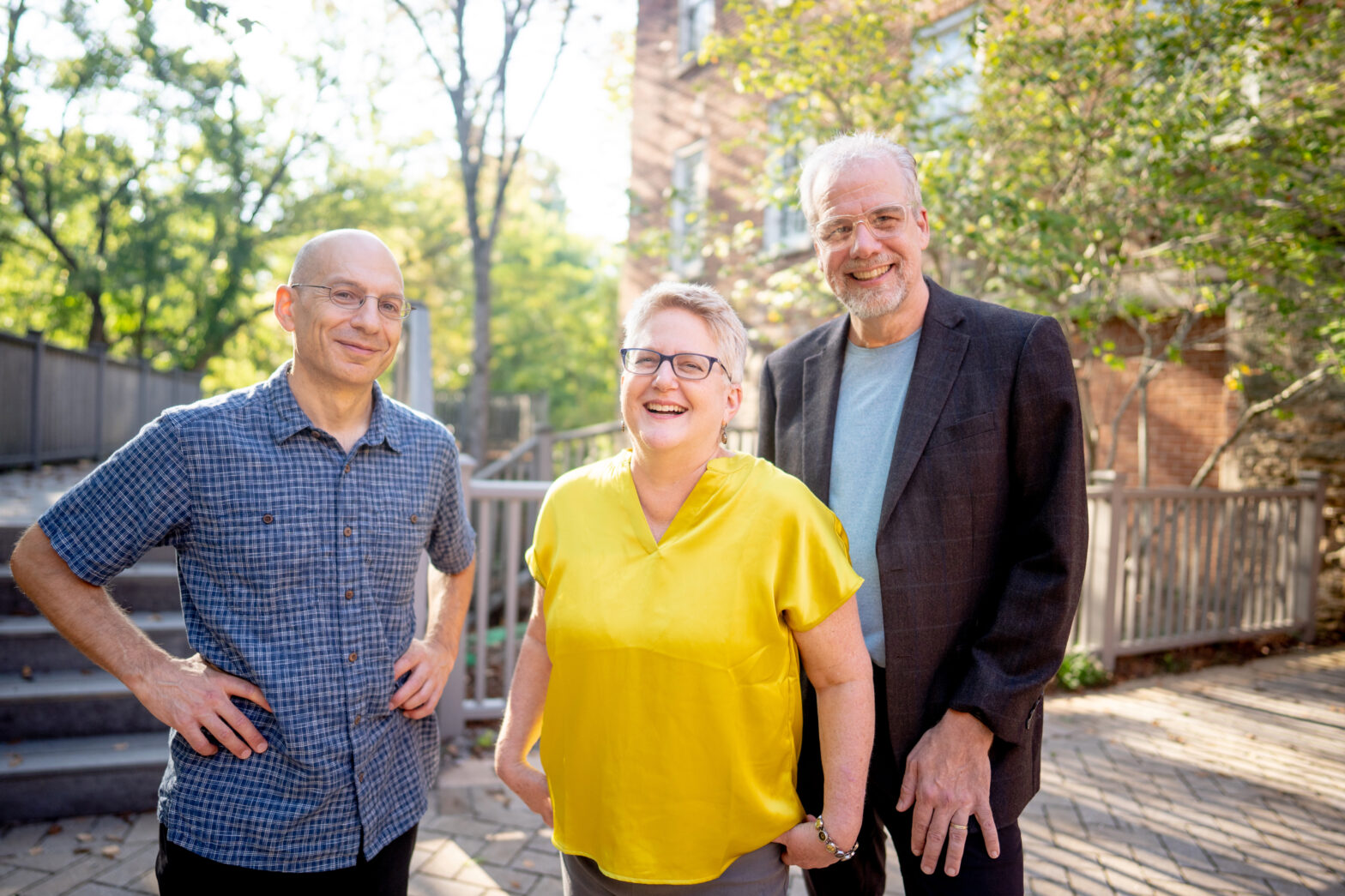

Since 2019, the Department of History in UGA’s Franklin College of Arts and Sciences has seen three faculty members awarded fellowships from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation. It’s a significant accomplishment that signals the university’s strengths in interdisciplinary humanities research.

“In the humanities, certain foundations, fellowships and awards are foundational to a life in learning among communities of scholars that are global in scope and scale,” said Nicholas Allen, director of UGA’s Willson Center for the Humanities and Arts. “The Guggenheim is one of these. The fact that the University of Georgia has been awarded three in the last four years shows how our humanities departments, when well led and supported, can lead the world, thanks in no small part to the individual brilliance of our professors.”

Guggenheim fellowships are intended for individuals who have already demonstrated exceptional capacity for productive scholarship or exceptional creative ability in the arts. They recognize scholars with the courage to ask the most difficult questions—and the experience to go about answering them.

Mapping the Cherokee nation

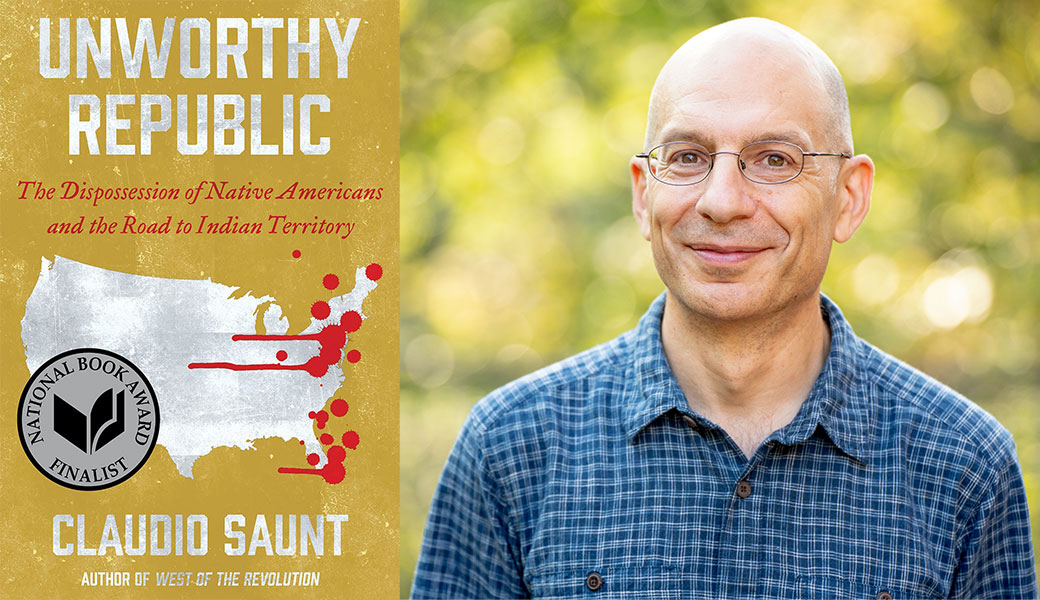

UGA’s most recent Guggenheim recipient is Claudio Saunt, Regents’ Professor and Russell Professor of American History. Saunt is using his 2022 award to create a digital map that brings the Cherokee nation of the early 1830s to life for scholars and the public.

One of the nation’s foremost scholars of Native American history, Saunt is the author of four critically acclaimed books, including Unworthy Republic: The Dispossession of Native Americans and the Road to Indian Territory (W.W. Norton, 2020), a finalist for the National Book Award and the winner of multiple prestigious prizes.

Saunt’s Guggenheim project, “The Land Beneath Our Feet,” draws on materials he discovered in the federal archives while writing that book: handwritten records from the mid-1830s documenting the homesteads of over 4,000 Cherokee residences—“almost down to the nail,” Saunt said.

The detailed notes, penned by government officials, describe the square footage of each Cherokee cabin, the type of logs, roofs and chimneys these structures had, the number and types of trees, orchards or outbuildings on the family’s land, and more. Taken together, the records paint a vivid portrait of the Cherokee at the level of the individual household in the years immediately prior to the deportation of the nation’s 16,000 citizens west of the Mississippi River.

How does one make such a treasure trove of information accessible? Saunt and his team are integrating the records into a comprehensive digital map. Viewers will be able to click on the interactive website, enter a town or street address in present-day western North Carolina, northern Georgia, eastern Alabama, or eastern Tennessee, and drill down to see what Cherokee residences once occupied the area.

The map will enumerate these 19th-century households with accuracy to within a quarter of a mile of their original location, an extraordinary level of specificity. Once the database is complete, additional facts from related records will be added over time, collectively creating a powerful memorial to the people of a remarkable nation.

“We have records of private property and movable property,” said Saunt. “Pots and pans, fiddles, canoes, bags of dried fruit. When the Cherokee were forced out, officers took that property and auctioned it off. So we know what these goods were, and we know who bought the property, too. All this information is available to us to help us tell the story of the Cherokee Nation.”

Saunt sees this retrieval as central to the historian’s task. “My job is to encourage people to engage with the past,” he said. “It’s very hard to be a good citizen if you don’t know the history of the country you’re living in. Most of us have very little sense that less than two hundred years ago, there was this whole other nation of people living in this part of the country. It’s important for us to understand.”

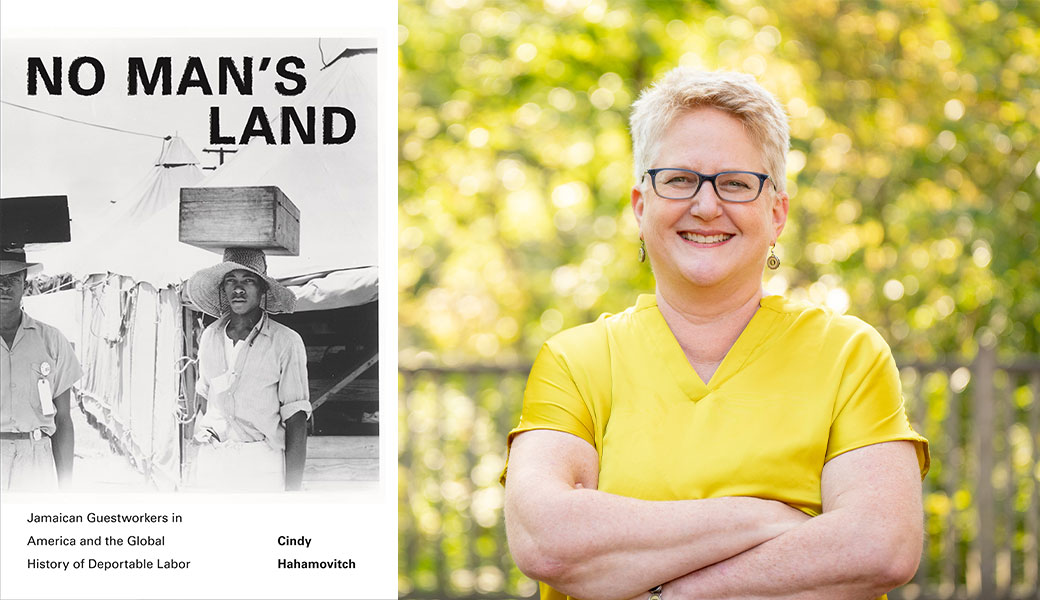

Exploited labor in an anti-slavery age

Like Saunt, Cindy Hahamovitch has organized her Guggenheim project around a history that often goes overlooked. Her book manuscript, “That Same Old Snake: Slaves, Coolies, Guestworkers, and the Global History of Human Trafficking,” is a global history of labor migrants since 1807.

It’s a gigantic project,” said Hahamovitch, B. Phinizy Spalding Distinguished Professor of Southern History and the recipient of a 2021 Guggenheim fellowship. “I’ve been working on it for about seven years, and I’m not done yet. The Guggenheim has given me time to write and to piece the pieces together, but of course, the more you write, the more you realize you don’t know.”

Hahamovitch’s first two books established her as a leading labor historian with particular expertise in the relationship between government policies and migration. Her second book won multiple national awards, and she has served as both a Fulbright fellow and a National Humanities Center fellow.

For her current book, she’s looking at how governments and employers moved poor people around the world for cheap labor in the decades following the official end of slavery. Throughout the 19th century, the British used indentured migration to move South Asians to British plantation colonies for work. That system, rife with abuses, ended in the 1920s. Yet Hahamovitch shows that modern governments in the present day use similar “guest-worker programs” to generate the same type of labor.

Guest workers today might have shorter contracts, and they might face deportation rather than jail time if they anger their employers, but the structural similarities between these practices and the exploitations of the 19th century are too many to be ignored. “Labor protections in contracts are just words on a page if workers can’t invoke them without fear of arrest or deportation,” she said.

And the more she learns about the history of these workers, the larger her Guggenheim project grows. Hahamovitch, who also volunteers as an expert witness in human trafficking cases, is currently immersed in a 6,000-page court transcript of a single lawsuit involving 590 highly skilled welders and pipefitters from India. These workers were brought to the United States on temporary work visas to repair oil rigs for Signal International in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in 2007.

The workers filed—and eventually won—a lawsuit against the company, after being required to pay $1,000 each per month for a bunk bed in trailers packed with 24 men to a structure, with no hope of ever paying off their debts and threats of deportation if they complained.

“My book will tell these stories to reveal how the world’s anti-trafficking efforts will remain feeble as long as states themselves are doing the trafficking by binding legal immigrant workers to particular employers,” Hahamovitch said.

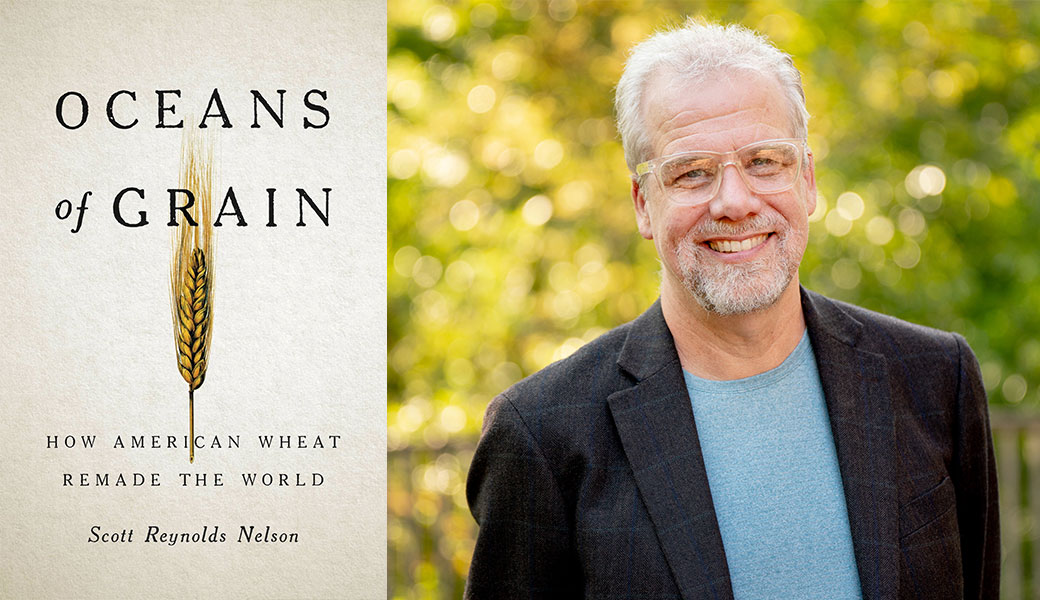

Food and empire

It’s rare to have three faculty members in one department receive a Guggenheim; it’s even rarer when two of those faculty members happen to be life partners. Scott Nelson, who is married to Hahamovitch, received the fellowship in 2019 to complete Oceans of Grain: How American Wheat Remade the World (Basic Books, 2022).

“This book was my white whale,” he said. “I never thought I would finish. It starts in 10,000 BCE and ends in 1924.” Having a partner—and a department—who understood the strenuous requirements of a major project helped, he said. So did support from the fellowship. “The Guggenheim gave me time,” he said. “Which is what historians need most.”

A specialist in 19th-century American social history and the author of multiple critically acclaimed books, Nelson set his sights extraordinarily high for this latest project: he wanted to write a global history of grain. His book shows how cheap American grain eventually felled the world’s leading empires, and it explores the parallel histories of Russia and the United States during the 18th and 19th centuries. To understand the rise and fall of empires, Nelson argued, we should take our cues from the paths traveled by grain on land and over water.

A key element in this global history involved a competition between two cities we don’t often think of as rivals: Odessa and Chicago. Nelson’s research reveals that the Union army and the railroad barons of the mid-19th-century United States sought to compete economically with the Ukrainian city of Odessa, then a dominant port city on an internal ocean. They built the city of Chicago to serve as an American competitor.

As he described this historic rivalry for the book, Nelson wrote that Ukraine has become the central piece missing from Russia’s superpower status in the present day. Two days after his book came out, Russia invaded Ukraine. Suddenly, a history that might have attracted a modest number of interested readers was catapulted into the global political discourse.

“The book blew up,” Nelson said. It was reviewed and discussed across international news and media outlets, including more than 30 podcasts. For a historian accustomed to audiences the size of a single classroom, being on camera for major television shows “was terrifying,” Nelson admitted. But he found his footing. He’s glad that his book had the chance to inform people about a key driver behind the latest Russian invasion of Ukraine—the link between food and empire building.

No shortcuts

Nelson, Hahamovitch and Saunt have each crossed disciplinary lines to pose fundamental questions: Who was here before us? How did they live? What motivates the building and tearing down of nations or empires? Upon whose backs was our present civilization built—and at what cost?

There are no shortcuts to answering such questions. But the effort deserves sustained attention. “History matters,” said Hahamovitch. “And I think historians have a responsibility to talk to anyone who will listen.”

Nelson is thankful for UGA’s ongoing support of interdisciplinary humanities research. “We’re in a department that lets us break down siloes, that doesn’t lock us in,” he said. “That’s an amazing benefit.”

It also helps to be at a stage in one’s career where empathy and taking the long view become easier. “Good mathematicians peak early,” Nelson said. “Good historians peak much later. A mentor once told me I wouldn’t be much good as a historian until I turned 50.”

He laughed and explained. “It’s that sweet spot where you haven’t yet started to misplace your shoes, but you’re able to see more broadly,” he said. “That’s the moment when everything starts clicking. That’s when you finally start putting the pieces together.”