Georgia’s Atlantic seaboard stretches from the northern tip of Tybee Island to the bottom of Cumberland Island to the south. While that distance measures only about 110 miles as the snowy egret flies, it’s marked by a series of 14 barrier islands that, all told, provide the state with some 3,400 miles of tidal shoreline.

Less developed than the shores of neighboring states, Georgia’s coast is home to some of the most diverse ecosystems in the world. Its nine major estuaries serve as a mixing bowl for fresh- and saltwater species that live in the eddies and marshes between the barrier islands and the mainland. That wildlife, both near the coastline and out into the Atlantic, underlies a commercial fishing and aquaculture industry that brings in $60 million in annual sales and supports nearly 1,000 jobs.

UGA operates three coastal research and service units, taking advantage of the area’s distinctive ecology, as well as serving the economic interests of the state and those who make their living in the lowcountry. Together, these three units work to provide knowledge that helps sustain the coast’s continued vitality while supporting an industry that is both dear to Georgia’s economy and threatened by environmental change.

UGA Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant

On the banks of the South Brunswick River researchers from UGA Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant stand knee deep in viscous, dark-brown pluff mud, placing bags of recycled oyster shells along the shoreline at Blythe Island Regional Park.

The team in Brunswick, Georgia, is studying different methods of restoring oyster reefs, which provide habitat and food for marine life, filter pollutants from waterways and reduce erosion by stabilizing shorelines along the coast.

It is just one of many Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant research projects that supports the health of Georgia’s coastal ecosystems and enhances community resilience. Since 1970, the organization has worked to improve the environmental and economic health of the Georgia coast through research, education and outreach. Funded by UGA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, it supports multidisciplinary research led by scientists from institutions across the state seeking solutions to critical issues impacting the Georgia coast.

Science-based applied research projects have included helping communities mitigate sea level rise, finding alternatives to ground-based septic systems and testing fishing gear that won’t adversely affect endangered sea life, such as the North Atlantic right whale.

“Our extension and education staff on the coast act as a bridge between scientists, local governments and marine industries by connecting university knowledge with local needs,” said Mark Risse, director of Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant. “They work to get solutions into the hands of the communities that need them most.”

Fisheries and aquaculture specialists study social and economic challenges impacting Georgia’s commercial fishing industries and provide training to aquaculture farmers to encourage practices that are sustainable, both environmentally and fiscally.

Stormwater, water quality, sustainable land use and coastal resilience specialists partner with local communities to identify areas that are vulnerable to flooding, storm surge, pollution or other coastal hazards before implementing demonstration projects that manage stormwater, promote green infrastructure and conserve water resources.

“We’ve worked with the cities of Tybee Island and St. Marys to create sea level rise and flood resiliency plans that inform adaptation measures,” said Risse. “Our goal is to provide knowledge, data and resources needed to prepare for and recover from coastal hazards through collaborative partnerships and community engagement.”

Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant specialists like Truck McIver (left) work with fishermen and aquaculture farmers to encourage environmentally and fiscally sustainable practices.

“Our extension and education staff on the coast … work to get solutions into the hands of the communities that need them most.”

– Mark Risse, Director, Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant

(Photo by Peter Frey)

In partnership with the Carl Vinson Institute of Government, also a Public Service and Outreach unit at UGA, Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant’s legal program responds to legal and policy questions from coastal communities, regional organizations and state agencies. The program supports effective management of coastal resources to improve resilience, encourage sustainable development and promote healthy coastal ecosystems.

The organization’s education staff offer youth programming and fellowship opportunities for college students that cultivate the next generation of educators and marine scientists. Many early career professionals who participate in these fellowships go on to work in marine science and policy, coastal resource management or environmental education.

“It transformed me from a graduate student to a professional, and it exposed me to different fields related to ocean issues outside of scientific research,” said Shiyu Rachel Wang, a 2017-2018 Knauss Fellow.

As part of the fellowship, Wang worked in the executive branch of the U.S. government, learning about policies affecting coastal resources. Wang, a UGA alumna, is now the assistant director of the Blue Pioneers Accelerator Program at the University of California, Santa Cruz, where she helps nonprofit leaders overcome ocean conservation challenges in China, Asia-Pacific and around the world.

Educators further engage coastal stakeholders in marine science through community science programs that focus on monitoring coastal habitats and wildlife through long-term data collection, improving understanding, conservation and stewardship of Georgia’s valuable coastal resources.

Skidaway Institute of Oceanography

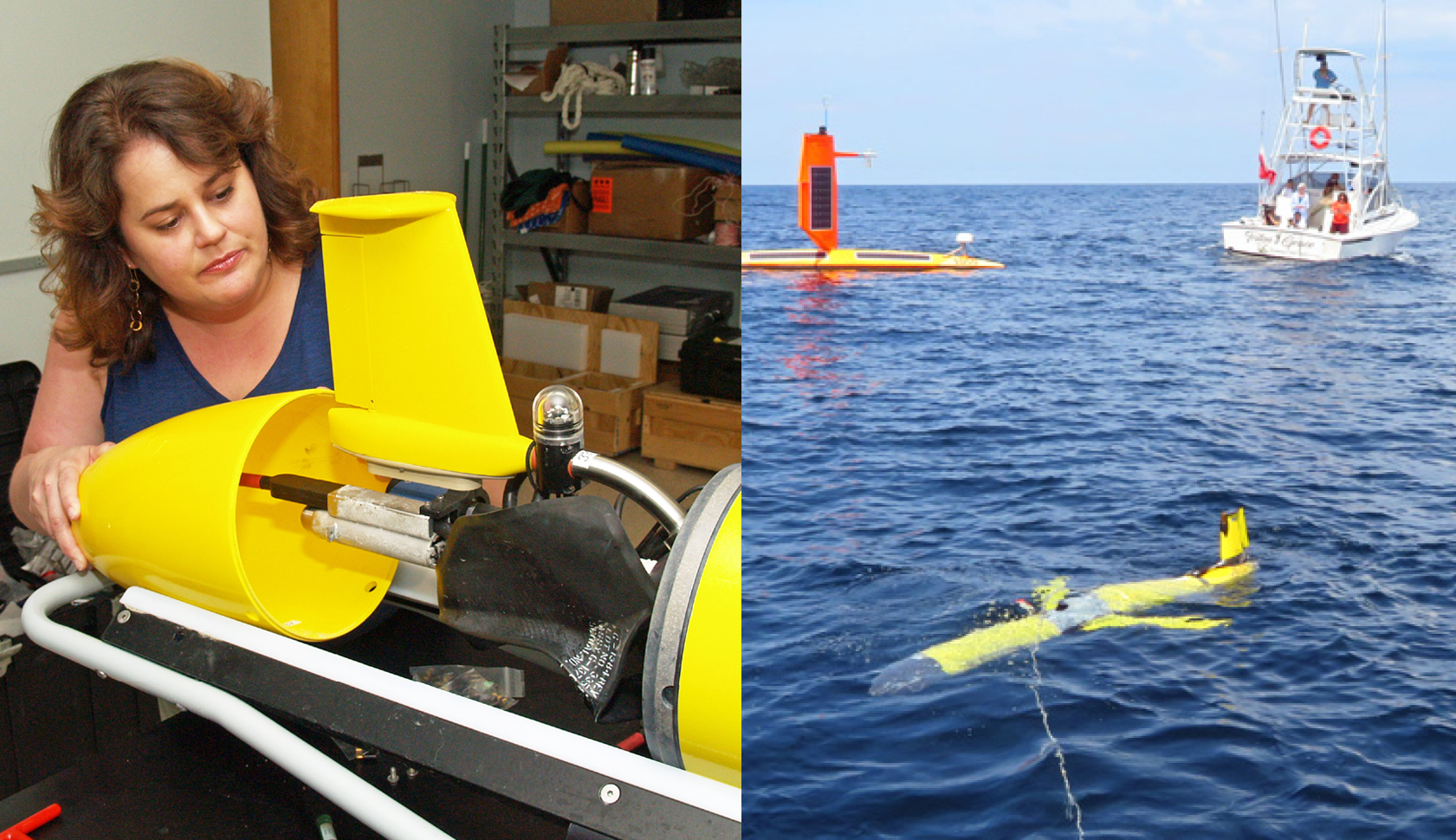

Oceanographer Catherine Edwards was sunburned and salt-sprayed, but filled with excitement when she stepped off a boat in Richmond Hill, Georgia, in early August. An associate professor at the Skidaway Institute of Oceanography in Savannah, Edwards is working to improve hurricane forecasts by using autonomous underwater vehicles or “gliders.”

These torpedo-shaped craft gather vital data on water temperature and salinity and transmit it in near-real time to improve the models that predict a storm’s intensity. Edwards had just completed three days of whirlwind activity from St. Petersburg, Florida, to Gray’s Reef National Marine Sanctuary, operating her gliders in tandem with wind-driven surface craft called saildrones, which gather and transmit complementary data at the surface.

Skidaway researcher Catherine Edwards (left) designs autonomous, underwater gliders that collect information that could help improve hurricane forecasting. During summer 2022, she worked with the U.S. Navy to deploy a glider and an above-water “saildrone” in Gray’s Reef National Marine Sanctuary, about 50 miles off the coast from Savannah.

“This is very exciting,” Edwards said. “Unlike most research, we can see the benefits of our work almost immediately, not months or years in the future.”

Edwards is one of 10 Skidaway faculty who teach undergraduate and graduate students, and who conduct oceanographic research across all the major disciplines (chemistry, biology, physics and geology). Their work extends from Georgia’s coastal estuaries to the deep ocean and around the globe, from the Antarctic to the Arctic.

UGA Skidaway Institute is located on a 700-acre campus on a coastal island in suburban Savannah. It was founded in 1968 when Robert and Dorothy Roebling donated their cattle farm to the state to form an oceanographic institute. Initially an autonomous unit of the University System of Georgia, Skidaway Institute was merged into UGA in 2013.

Skidaway Institute includes state-of-the-art biological, chemical, geological and physical oceanographic research laboratories, a number of specialized facilities, and new educational facilities to support graduate and undergraduate instruction. The institute also operates the 92-foot Research Vessel Savannah—part of the U.S. academic research fleet—as well as several smaller vessels to support estuarine and coastal ocean research and education.

Edwards’ work is an example of the growing trend at Skidaway Institute of utilizing advanced technology to unlock the ocean’s mysteries. One scientist is working to develop the use of nanosatellites to study ocean color. Another uses a revolutionary imaging system and artificial intelligence to study how tiny ocean animals live in their natural environment, while others study some of those same creatures by examining their DNA. Drone technology is being used by one team to study how beach erosion is affecting human-made beaches and sand dunes on Georgia barrier islands.

“Technological advances have accelerated the pace of scientific discovery in the marine sciences,” UGA Skidaway Institute Director Clark Alexander said. “New techniques, particularly in remote sensing and robotics, provide detailed insights that were impossible to achieve using prior methodologies.”

Edwards believes her glider work will have long-term benefits for those in the paths of hurricanes. “Ultimately, we hope these operations will save lives by helping forecasters better predict the intensity of an approaching storm,” she said.

UGA Marine Institute on Sapelo Island

Sapelo Island, home since 1953 to the UGA Marine Institute, sits just off the Georgia coast about 70 miles south of Savannah. Separated from the mainland by a labyrinth of tidal creeks and marshes, the 12-mile-long barrier island is reachable only by ferry.

Eugene Odum—aka the father of modern ecology—jumped at the chance to create a research station on Sapelo in the early 1950s, and for good reason: Protected from most development by the state of Georgia, the island’s inaccessibility and pristine shorelines combine to make it an ideal location for research on estuaries and tidal marshes. Each year, UGA receives nearly $2 million in research funding that relies in some way on UGAMI and its facilities.

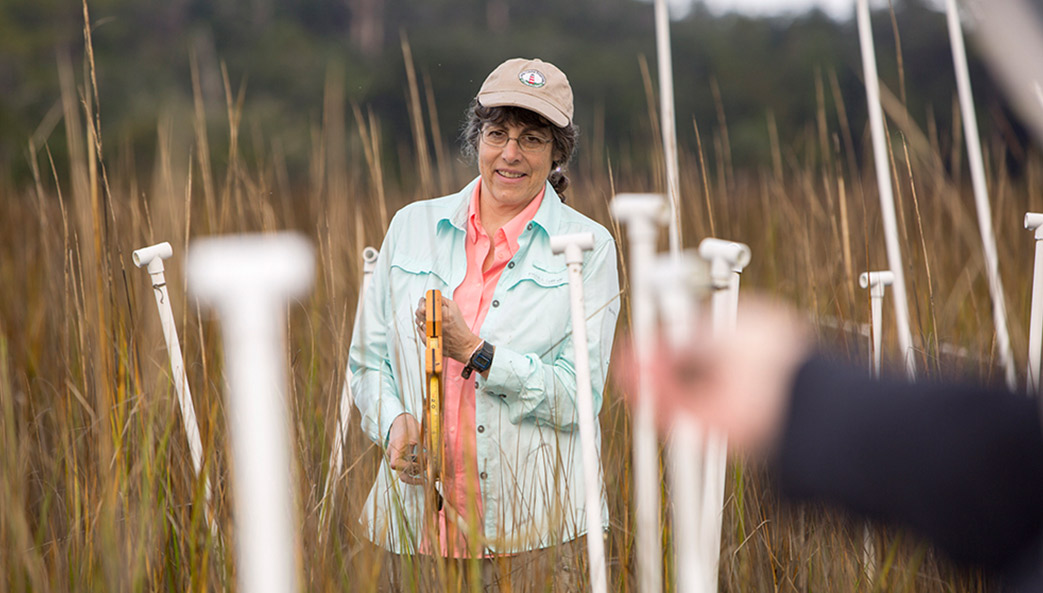

“UGAMI is a thriving field station with a far-reaching constituency of researchers and educators who value the natural laboratory of Sapelo Island and continue to build on the institute’s scientific legacy,” said Director Merryl Alber.

For 22 years, UGAMI has served as the home base for the Georgia Coastal Ecosystems Program, a Long-Term Ecological Research project supported by the National Science Foundation. GCE’s mission is to understand estuaries and intertidal wetland ecosystems, how they respond to long-term change, and how they might be affected by future variations in climate and human activities. Most of GCE’s affiliated researchers are from UGA, and the rest hail from universities across the country. In recent years, UGAMI has hosted scientists from 27 institutions, including researchers from the Netherlands, Czech Republic and China.

But Sapelo is a boon for more than ecological research. UGA’s Laboratory of Archaeology conducts long-running excavations related to the island’s indigenous cultures, whose tell-tale shell ring complexes can still be seen thousands of years after their builders left for the mainland. Recently UGA researchers demonstrated that Sapelo’s native residents did not depart the island suddenly in the face of rapid environmental change (which was the prevailing view among anthropologists), but rather they persisted for centuries, continually adapting to forces that threatened their traditional ways of life.

UGAMI also shares the island with the residents of Hog Hammock, one of the last remaining Gullah-Geechee communities in the United States. Hog Hammock’s residents have themselves dealt with centuries of long-term change. UGA faculty have partnered with the community and its representatives to help preserve the Gullah culture as it endures in the face of a changing world.

UGAMI hosts more than 4,000 annual overnight stays by students and researchers from not only the Southeast but around the globe. Its location among the estuaries and tidal marshes of coastal Georgia make it one of the world’s premier locations to study coastal ecosystems; since 2000, it has served as the home base for Georgia Coastal Ecosystems, a Long-Term Ecological Research Project funded by the National Science Foundation. (Photos by Peter Frey, Andrew Davis Tucker and courtesy of UGAMI)

Finally, the institute hosts hundreds of university students each year for UGAMI-based courses and field trips that immerse students in field-based academic studies. At least 10 University System of Georgia institutions regularly send students to Sapelo, as do numerous colleges in the region. In all, UGAMI hosts more than 4,000 overnight stays annually by students and researchers.

“UGAMI’s mission is to provide exceptional opportunities for research and education in coastal ecosystems, and that is something we always keep in mind,” Alber said. “On top of our long-standing activities, we now offer residential educational programs, and we have just welcomed our first scientist-in-residence, which is a rotating position for an early career scientist. We have also made substantial improvements to the facilities over the past few years, and those efforts continue. It is truly rewarding to see these new projects coming together.”