Biomanufacturing has been around for thousands of years, though it wasn’t called that when our ancestors were making beer, wine, cheese, bread and vinegar. Mankind has long understood the value of fermentation, the metabolic process of converting things like sugar or starch into alcohol or acid.

At the University of Georgia, biomanufacturing is based at the on-campus Bioexpression and Fermentation Facility, which has been churning out important research and services for Georgia research faculty and students—as well as industry clients from around the world—for more than a half-century. As the largest such facility in the Southeast, the BFF is poised to become a critical player in the next generation of biomanufacturing.

“What you have in BFF is fairly unique,” said Darcy Prather, president of Boston-based Kalion Inc. and a BFF client for eight years. “There are only a few places in the country that have capabilities like that, and those places are not in the traditional high-tech areas. As important as it was when UGA first started it, I would argue that the capabilities of a place like BFF are even more important today.”

“What you have in BFF is fairly unique. There are only a few places in the country that have capabilities like that, and those places are not in the traditional high-tech areas. As important as it was when UGA first started it, I would argue that the capabilities of a place like BFF are even more important today.”

– Darcy Prather, CEO of Kalion Inc., a BFF client company

Producing next-gen materials

In the 20th century, biomanufacturing has created things like ethanol, penicillin, protein drugs (such as insulin), monoclonal antibodies and vaccines. The new generation of biomanufacturing is a cornerstone in developing regenerative tissues, renewable energies, food sources and other commodities for the sustainable revolution.

BFF director David Blum tries to distill what his facility does in a simple soundbite.

“We’re using cells to make products,” Blum said of his 9,500-square-foot lab that facilitates research services across four divisions—fermentation, protein purification, cell culture and monoclonal antibodies. Its work involves everything from the cloning and expression of genes to development of vaccines, to fermentation of bacteria capable of growing at the temperature of boiling water, to working with mammalian cells that can produce certain kinds of proteins better than bacteria.

Its mission, said Blum, “is to provide these biotech services to UGA faculty, other academic institutions and industry, mainly because they don’t have that equipment themselves. It’s offering a service that provides value to our customers.”

The BFF facility houses state-of-the-art equipment: computer-controlled bioreactor fermentation tanks ranging from 750 milliliters to 800 liters; chromatography instruments for purifying proteins; and lyophilizers for freeze drying samples. The equipment (and the staff experienced in using it) has grown more invaluable than ever as it produces results for UGA researchers and industry clients worldwide.

“In any one year, there could be up to 50 different external entities that we’re working with, from a small startup company to a multinational corporation,” said Blum.

“Having a facility that has the breadth and depth of our equipment is really important not only for companies that have limited equipment but small startups that are just virtual and have no labs of their own,” Blum said. “The tanks we have are more advanced than what you see in a brewery because they have the motors and sensors, so we know the pH and oxygen level in the tanks, and we can control the tanks, as far as how much air and pH they have.”

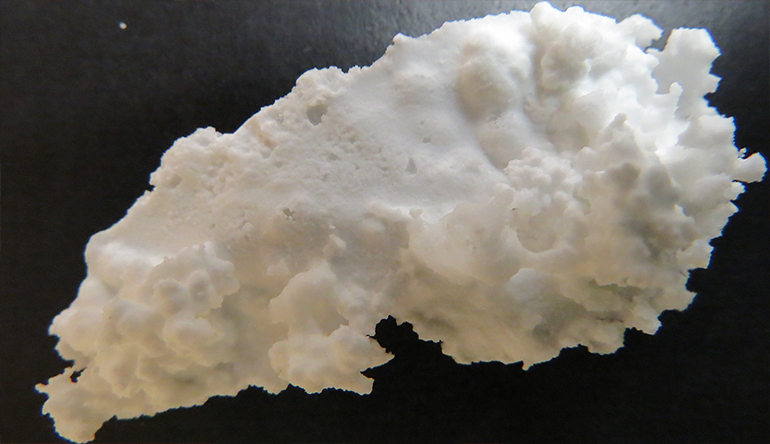

Prather can advocate for BFF’s services as an industry client. His wife, a professor at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, discovered a bio-based route for producing glucaric acid—a valuable and versatile molecule that can be used commercially to make pharmaceuticals and detergents or to dramatically increase the tensile strength of recycled organic fibers. Traditionally, glucaric acid is manufactured using expensive chemical processes.

“Most academic researchers are just trying to say, can I produce any of this material?” Prather said. “But for it to be commercially relevant, you’ve got to produce a lot of it. There’s a bit of a gap, and BFF has been instrumental in supporting us and helping us get through that gap, essentially.”

Kalion turned to the BFF for what it calls “process optimization,” determining which proprietary fermentation processes are appropriate to turn E. coli bacteria into pure, low-cost and environmentally friendly glucaric acid at a commercial scale. With that, the company can generate bio-based products and applications including water treatment, polymers and textiles, coatings, detergents and pharmaceuticals.

“That optimization is adding different materials, using different amounts, changing times when we add materials,” said Prather. “Using the fermenter that they have at BFF allows us to precisely control when you add materials to it. By having more precise control, you can optimize it.”

Kalion has been a BFF client for seven years, choosing UGA’s services based on reputation and price. The relationship allowed Prather’s company to stay virtual as it tried to perfect the process to produce glucaric acid at a commercial scale.

“When we leave BFF we have, for the most part, a flask full of ‘dirty’ liquid,” Prather said. “If you’ve ever brewed beer, it looks like that. You separate out the material that you actually want from that.”

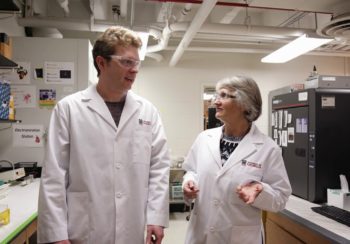

Maya Cornish (right) was still a senior at Clarke Central High School when she began working with Blum at the BFF through UGA’s Young Dawgs Program. “My hope,” Cornish said, “is that students … get to learn more about the BFF. I didn’t know that there are so many different things you can do with a pharmaceutical degree or a biomanufacturing/ bioengineering degree.” (Photo by Jason Thrasher)

Training next-gen scientists

Blum also is director of UGA’s Master of Biomanufacturing and Bioprocessing (MBB) program, which trains science and technology graduates for leadership roles in this rapidly expanding and important field.

While the BFF is in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology in the Franklin College of Arts and Sciences, Blum’s graduate MBB program is housed in the College of Engineering School of Chemicals, Materials and Biomedical Engineering, which offers several courses in fermentation and how to process materials and purify proteins.

Blum also collaborates with the College of Pharmacy in developing biopharmaceuticals. A workforce development program is offered through the UGA Center for Continuing Education & Hotel, in an effort to attract more people to opportunities available in biomanufacturing.

“A lot of schools don’t have these training programs, and they are really not very well known. We’re training students to go into careers in biomanufacturing,” Blum said. “It provides more options for students who don’t know what they want to do with their degree. The big message is that we have this pilot plant and we provide these services that have value to our customers, but it’s also valuable to students to know how to do this.”

One of those students is Maya Cornish, 19, who was introduced to the BFF by Blum through the Young Dawgs Program while she was a senior at Clarke Central High School. Despite COVID shutdowns in 2020-21, Blum welcomed Cornish into his lab.

“It was pretty much the height of the pandemic, so not that many labs were accepting students, not to mention high school students who have no experience and no qualifications,” said Cornish, who is double majoring in pharmaceutical science and Russian at UGA. “But Dr. Blum was fortunately one of the few who was open to having students.

“When I first started with him, I was intimidated by the facility and all the opportunities it held, not only for students like me but for people at different stages in their life,” Cornish said. “There are professional scientists who work here, professional researchers, graduate students who are working on their master’s and Ph.D. degrees. This facility brings a lot to UGA.”

Cornish worked on a BFF project developing a potential inexpensive, at-home COVID-19 test kit. What she got out of the experience—aside from a role working with Young Dawgs and serving as the social media coordinator for the BFF and MBB—was a glimpse at the array of career possibilities in biomanufacturing.

“My hope is that students, especially students interested in bioengineering and biomanufacturing, get to learn more about the BFF and the opportunities we present not only in a professional sense, but also in an educational sense,” she said. “I didn’t know that there are so many different things that you can do with a pharmaceutical degree or a biomanufacturing/ bioengineering degree.”

A recent grant from BioMADE, a manufacturing innovation institute, enables BFF to develop a cost-effective, do-it-yourself bioreactor to increase student access to biomanufacturing training and equipment.

“If you want to go out and buy a fermenter, just the entry-level fermenter for your classroom if you’re a teacher, it’s going to cost you anywhere from $25,000 to $100,000,” said Blum. “That’s a huge barrier, especially if you’re a rural technical college, or even UGA.”

But, Blum said, a DIY system can be built with a tank, a motor and some sensors that are available in the open market.

“You could have something that’s maybe not as functional as our $100,000 system, but it still helps you with your learning objectives,” he said. “What we’re trying to do is build something that a small college could build themselves, and we’re going to have a workshop this summer to teach these professors how to do that. We call it a souped-up shake flask.”

It’s all part of a bigger picture that UGA has been working toward since the BFF opened 55 years ago.

“Georgia has the potential to be a very important state in the bioeconomy, because you’ve got a lot of big timber industry and agriculture, and the BFF will be a critical piece of that,” said Prather, whose experiences with UGA’s facility has him bullish on its future value. “If we’re really going to a renewable economy, then investments in places like a BFF can accelerate the development of that economy.”