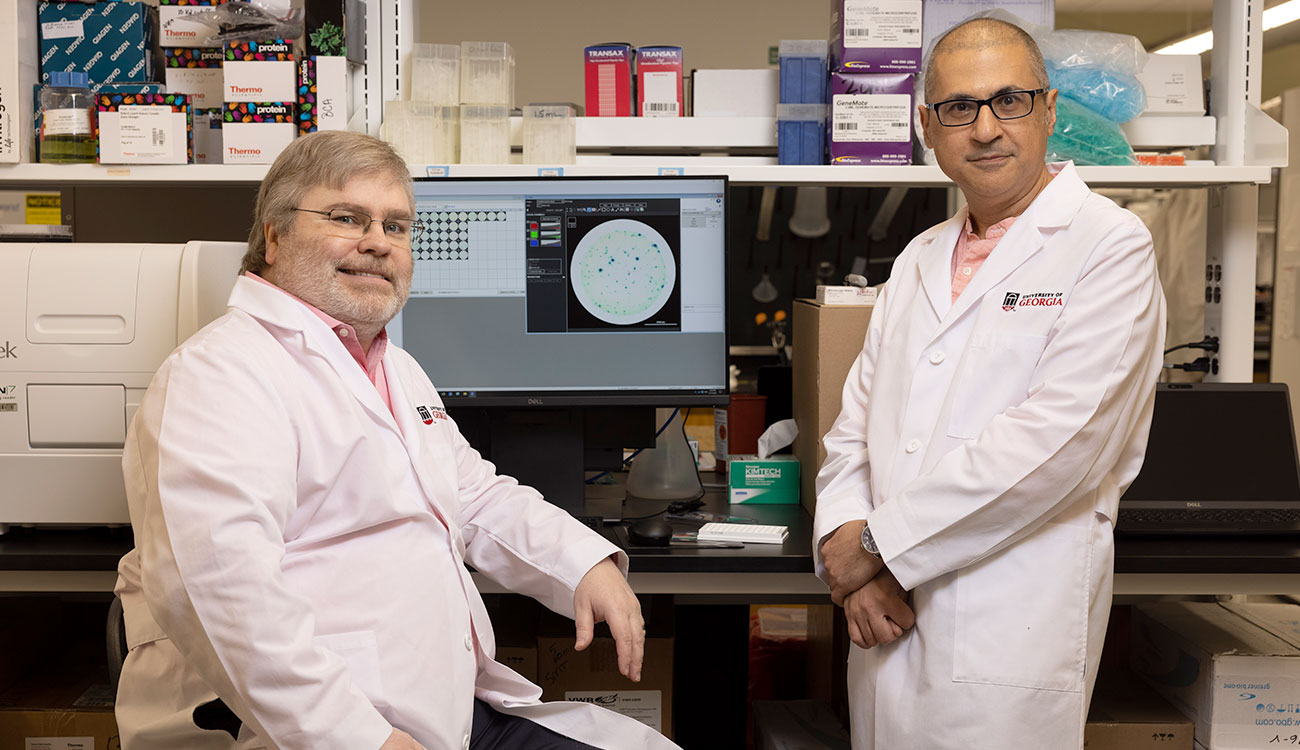

Two years ago, UGA scientist Mark Tompkins decided to submit an independent proposal for an influenza virus research contract to the National Institutes of Health. He’d been a sub-awardee with Emory University on an earlier contract, but putting together his own team and proposal seemed daunting.

Fortunately for Tompkins, UGA was ramping up exactly the kind of support he needed. After several months of intense preparation, funds awarded from UGA’s Teaming for Interdisciplinary Research Pre-Seed Program allowed him to put together a one-day, in-person meeting in January 2020—with four members traveling from out of town—that helped the team’s plan take shape.

“That was really a key thing that helped us solidify the research components of the proposal,” said Tompkins, professor of infectious diseases in the College of Veterinary Medicine. “We were able to structure the research components of the grant and identify gaps that needed to be filled. We fleshed out the idea there.”

The help Tompkins received is just one example of the support network UGA is building for faculty as they seek funding for projects that will take the university’s research—and its impact—beyond the borders of campus to the state, nation and world. That effort is led by Larry Hornak, associate vice president for research, integrative team initiatives.

“Enabling our faculty teams to realize their visions is how we can change the world, and these types of projects are how we do it,” he said. “We’re trying to give faculty the support and professional development they need to organize and execute these high-impact projects, whether that’s in 21st-century infrastructure, infectious disease, precision agriculture, marine sciences or what have you.”

The university’s efforts, which run the gamut from pre-seed grants to team science workshops to hiring off-campus experts to review large proposals, are paying off.

Tompkins’ proposal to establish the Center for Influenza Disease and Emergence Research was funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, part of NIH. The CIDER contract provides $1 million in first-year funding and is expected to be supported for seven years—and up to approximately $92 million—as he works to increase understanding of influenza virus emergence and infection in humans and animals.

Cultivating team leaders

“It’s always been my dream to have a long-term observatory in the Gulf of Mexico,” said Samantha Joye, Regents’ Professor and Athletic Association Professor of Arts and Sciences in marine sciences, part of the Franklin College of Arts and Sciences.

“We’d go out four to six times a year and really be able to see how processes and communities are changing hand in hand and how that propagates up the food web. That’s a powerful approach that can be translated and used in other parts of the ocean, because that’s what we’re going to need to really understand how oceanic systems are responding to climate change.”

That kind of project requires expertise in a variety of fields, which means seeking collaborators from institutions all over the world and forming an effective team with them. Team science best practices—including those that go beyond the academic world—are key. The university, keeping its land-grant mission in mind, wants to lead the way in solving hard problems that don’t fall into neat disciplinary or organizational bins.

“To truly create meaningful impact that changes people’s lives through our externally funded research requires teams that include public and private sector partners,” Hornak said, “so we can make innovations accessible to those who need them.”

These kinds of integrative teams are what sponsoring agencies look for.

“They want proposals that create the bridge to impact,” he said. “They’re looking to plant the seeds of sustained impact, not just in the literature and research, but in other areas like economics, environment, education, diversity, equity, inclusion and more.”

With help from Hornak and the team in the Office of Proposal Enhancement, Joye was able to put together her dream proposal.

“They suggested changes—large and small—that substantially improved the structure, quality and cohesion of the proposal,” she said. “And Larry’s insight was a game changer for us.”

Joye’s proposal to the National Science Foundation includes more than 30 researchers at a dozen institutions in the U.S. and abroad—the kind of team that presents logistical challenges and requires predetermined leadership strategies. So she participated in another of Hornak’s initiatives, the Leading Large Integrative Research Teams, or L2-IRT, workshop series led by Dorothy Carter, who researches leadership and large-scale collaboration.

“As a faculty member, you get into something based on the intellectual questions,” said Carter, associate professor of psychology in the Franklin College. “Then you find out that on top of that you need to be an accountant, a sales person, a web designer and a social media person, and you also need to learn management and leadership skills on a bigger and bigger scale over time.”

Hornak has sat on panels to select these kinds of proposals before. When they’re rejected, sometimes it’s not because the science is not important or because the research questions are not interesting. It’s because the proposal didn’t demonstrate that the team was going to be able to execute the project.

“That is something you can demonstrate in the management plan,” Carter said. “We can demonstrate that we have people who understand how teams work and how organizational structures need to look to get the work done.”

In its second year, the L2-IRT program is continuing to help faculty envision their dream projects, but also emphasizing hands-on opportunities. Participants can emerge from the workshop series with a proposal-ready document that addresses management structures.

“It’s almost like a charter that everyone signs onto so that everyone knows how to move forward together,” Carter said.

“They reviewed our proposal and gave us critiques, and we were able to significantly improve our proposal based on their feedback. I think that is very, very helpful.”

– Changying “Charlie” Li, professor, College of Engineering

Photo by Amy Ware

Facilitating collaboration

In a recently published paper on marine parasites and disease, UGA ecologist Jeb Byers did something unusual—he discussed a conversation he had with Al Camus, a colleague in the university’s College of Veterinary Medicine.

“An ecologist would say there are only a few dozen diseases that are problematic in the ocean. Al said, ‘I teach nearly 1,000 fish diseases.’ The disconnect is because we’re defining things differently, and we’re looking for different levels of evidence,” said Byers, professor in the Odum School of Ecology. “It was eye opening. His perspective on the topic really turned my head around.”

This kind of broadened perspective is a hallmark of the Presidential Interdisciplinary Seed Grant program, another tool in the integrative team initiatives toolbox that’s designed to encourage interdisciplinary collaboration and support teams as they collect preliminary data for a larger grant proposal.

For the second round of grants offered, more than 70 faculty teams submitted research proposals, and seven teams were selected to receive research awards from the $1 million available for the program. The third round of grants will be supported by $1.5 million made available by President Jere W. Morehead. Award announcements are expected by the end of fall semester.

Byers’ team was awarded funding during the second round.

“We’ve pulled together a group of people that work in very different areas. Each of these people brings a different perspective and different toolbox,” Byers said of his team. “That’s been one of the most intellectually engaging parts of this project.”

Want help getting funded? Here’s where to start

Provides $500 grants per faculty member to facilitate the formation of interdisciplinary teams around critical areas of expertise or emerging research topics.

Presidential Interdisciplinary Seed Grants

Once teams are established, the program provides grants of $50,000 to $150,000 to develop a team’s idea and collect data for a larger proposal.

A series that helps faculty with a track record of interdisciplinary research to take the next step and lead large, integrative research teams.

Provides technical and skilled support to faculty across campus who are developing research proposals for external funding.

Recognizes a team for excellence in innovative and impactful scholarship with the potential to fundamentally advance knowledge, understanding and/or applications.

Fred Quinn is leading a project that explores influenza-tuberculosis co-infection and factors including vaccination and immune response.

“When I was getting my Ph.D., the mantra was that you would work by yourself or with your laboratory on one project for your entire career,” said Quinn, Athletic Association Professor of Infectious Diseases in the College of Veterinary Medicine. “I don’t find that particularly fun. Our collaborators have been a blast to work with.”

For a team led by Brian Bledsoe, Athletic Association Distinguished Professor in Resilient Infrastructure in the College of Engineering, the seed grant contributed to the development of a $56 million proposal to the National Science Foundation to establish an Engineering Research Center. In developing the proposal, Bledsoe collaborated with numerous stakeholders, including eight different universities and more than a dozen private-sector groups.

Quinn finds value in this kind of broad approach—and so do funding agencies, he said.

“I really do enjoy spreading our wings and getting other people interacting, and that’s what most funding agencies want,” he said. “They want collaborations, not just within an institution but across institutions.”

Soliciting expert input

The word “project” is not quite big enough to encompass Bledsoe’s proposal for the Sustainably Engineered Riverine-Coastal Systems Engineering Research Center. The vision is to build something that will have a long-term benefit for society, something that he hopes will last beyond his time.

“It’s not one of those projects where it’s got a tidy end date,” he said. “It’s trying to do something transformational and essentially change how we approach infrastructure. We want to create infrastructure that’s resilient in the face of climate change and deliver more benefits and services to society, including disadvantaged and rural communities that often don’t get as much attention.”

His vision builds on the work done at the Institute for Resilient Infrastructure Systems, which he has directed since it was founded five years ago. Bledsoe also participated in the L2-IRT program, creating a team charter that established ground rules in the culture of inclusion, diversity and transparency that he’s seeking to create.

“It takes a lot of time to get to the point where you’ve got a shared vision and are ready to move into action,” he said. “You’ve got to learn the vocabulary of other disciplines. And we’re all thinking about different scales. Is it local, regional or national? And we’re thinking about different time scales too. The geologist is thinking about what happened over the last several thousand years, the economists might be thinking about what’s happening next month or next year, and the engineers are focusing on the next 20 or 30 years. We’re trying to meet across all these different scales with all our jargon and different tools in the toolbox.”

While Carter helps team leaders articulate their vision, Jake Maas facilitates input from independent experts who can assess a proposal’s chances for success. These are known as Red Team reviews.

“These are people who’ve been program officers at NSF or have successfully managed large centers of the type that we’re applying for,” said Maas, director of proposal enhancement. “That’s been a very successful process. It galvanizes the team. It helps everyone on our side to take it seriously because it’s going to be reviewed by people whose opinion they care about, and it takes place early enough that there’s time to address their comments and suggestions.”

Bledsoe’s proposal benefitted from Red Team reviews at the pre- and full proposal stages, he said.

“Larry and Jake, they helped us identify Red Team reviewers who had really deep experience and knowledge of both the subject matter and how these centers work, and what NSF was really going to focus on,” Bledsoe said. “That was invaluable, and we took their advice to heart.”

Another researcher from the College of Engineering, Changying “Charlie” Li, submitted a large team proposal to NSF to apply artificial intelligence to agricultural challenges at different scales, from individual plants and animals to watersheds and markets. The proposal included 40 investigators from different disciplines (engineering, computer science, plant pathology, poultry science, agricultural economics, social science, agronomy) and 10 institutions around the nation. His proposal also went through a Red Team review.

“They invited three highly qualified reviewers,” said Li, professor of electrical and computer engineering. “They reviewed our proposal and gave us critiques, and we were able to significantly improve our proposal based on their feedback. I think that is very, very helpful.”

He also received a pre-seed grant.

“Support from the institution for large grants is very important. The team science workshops, the pre-seed grant, the presidential seed grants—those are critical to putting together competitive proposals,” Li said. “Individual faculty members cannot succeed if they work alone on these large, complex grants. We need the institutional support.”

Building a vision

In September, NSF announced that it was funding a proposal for a new center devoted to the ocean’s microscopic world. UGA’s Mary Ann Moran will serve as co-director and research coordinator.

“We can’t actually watch what ocean microbes are doing because of their extremely small size, yet they are literally driving the major carbon and nutrient cycles that keep the planet alive,” said Moran, Regents’ Professor in marine sciences in the Franklin College. “Better understanding of this network of microbes and chemicals will improve our ability to predict the way the ocean works, now and in the future.”

The Center for Chemical Currencies of a Microbial Planet, or C-CoMP, is funded for $25 million over five years, with an option for five more. It’s a quintessential example of team science that includes researchers based at UGA plus 11 other universities and institutions around the country. UGA’s Art Edison, GRA Eminent Scholar in the Complex Carbohydrate Research Center, and Erin Dolan, professor of biochemistry and molecular biology, Georgia Athletic Association Professor of Innovative Science Education, will serve as senior researchers for C-CoMP.

Team projects will be an invaluable part of UGA’s research portfolio moving forward, according to Karen Burg, vice president for research.

“UGA scientists are committed to tackling—and solving—the world’s toughest problems,” she said. “Team projects allow us to leverage our strengths and combine them with others’ for maximum impact. We know our researchers bring great technical expertise to a collaborative initiative; our goal is to ensure they also have the unique skills needed to lead and be valuable contributing members of widely diverse teams.”

And success with these kinds of proposal doesn’t happen overnight, according to Hornak. It requires a strategic approach—one that his network of support can help with.

“What we’re really stressing with the teams is to establish what your vision is and how you’re going to work well together. Then develop the larger network of collaboration that you’re going to need to make an impact,” he said. “If you do those things, that will align with what the programs are looking for. You won’t just be reacting to a solicitation—you’ll already be aligned with what you know funding agencies are trying to achieve. You’ll be not only ahead of the curve, but helping to define it.”