When Willis first stepped on a stage, Athens already enjoyed an international reputation for music—just not the kind of music he made. Still, he is one of hundreds, perhaps thousands of artists over the decades who’ve lived in this town and dreamed of making music.

Each story is different. All of them contributed to make Athens the community it is today.

Willis’ story is recorded, along with more than 100 others, as part of the Athens Music Project—an expansive, multi-phase endeavor that began nearly a decade ago and lives on today through the efforts of UGA’s Special Collections Libraries. With the goal of documenting Athens’ music history from all perspectives and genres—not just the independent/alternative rock scene that brought the city international attention beginning in the late 1970s—the project encompasses interviews with musicians with roots in indie rock, hip hop, folk, gospel, rap and other flavors that have been represented and flourished in Athens since the early 1900s.

The full catalog of interviews—which is available online for anyone to access—includes familiar names like the B-52s’ Cindy Wilson and Vanessa Hay of Pylon fame, but also many more that did not enjoy similar fame but had tremendous influence through their lives and work—names like gospel singer Zeke Turner, or longtime Athens High School band director Walter Allen Sr., or Athens rapper Ken “Duddy Ken” Richardson, as well as a range of music writers, club owners and others who loomed large in the city’s music culture.

“Athens was home to many music communities, and those communities were very diverse,” said Christian Lopez, a librarian and archivist who directs the Richard B. Russell Library for Political Research and Studies’ Oral History Program. “One of the big questions we’ve had as archivists and library employees has been, ‘We’re in this music town—why don’t we have more Athens music collections?’”

“Not everybody creates a paper trail that documents their life’s work—not everybody writes letters or keeps a diary,” said Toby Graham, associate provost and university librarian. “Oral history gives us an opportunity to tell those people’s stories. There is no tool available to us that’s more successful at diversifying our collections and documenting the underdocumented than oral history.”

“Oral history is absolutely critical when you’re doing ethnomusicology. You spend a lot of time listening, asking questions, and spending time to get all this information. It was just a natural, good fit for us.”

— Christian Lopez, Special Collections librarian and archivist

Bringing Georgia music home

At its beginning, the Athens Music Project focused on the African American experience. In the early 2000s, Professor Jean Kidula in the Hugh Hodgson School of Music began teaching a course on the history of African American music, and one of the assignments was to do original research on black musicians. By the second iteration of the course, she realized there was a problem.

“The students didn’t seem to have any Georgian role models [from earlier eras],” Kidula said. “Not because there weren’t Georgians, but because almost every Georgia musician moved north to have a career. We’re talking about the 1920s and 1930s.”

Her quest to find source material for her students led Kidula to the Georgia Music Hall of Fame in Macon—just before the Hall of Fame closed its doors in 2011. There was talk of bringing the Hall of Fame to Athens, but funding for a dedicated, bricks-and-mortar presence did not materialize. Meanwhile, the lights were going out in Macon, Georgia.

“The place closed and there was no place for the Hall of Fame collection to go,” Graham said. “We had not yet finished the Special Collections Building. But we had finished the vault.”

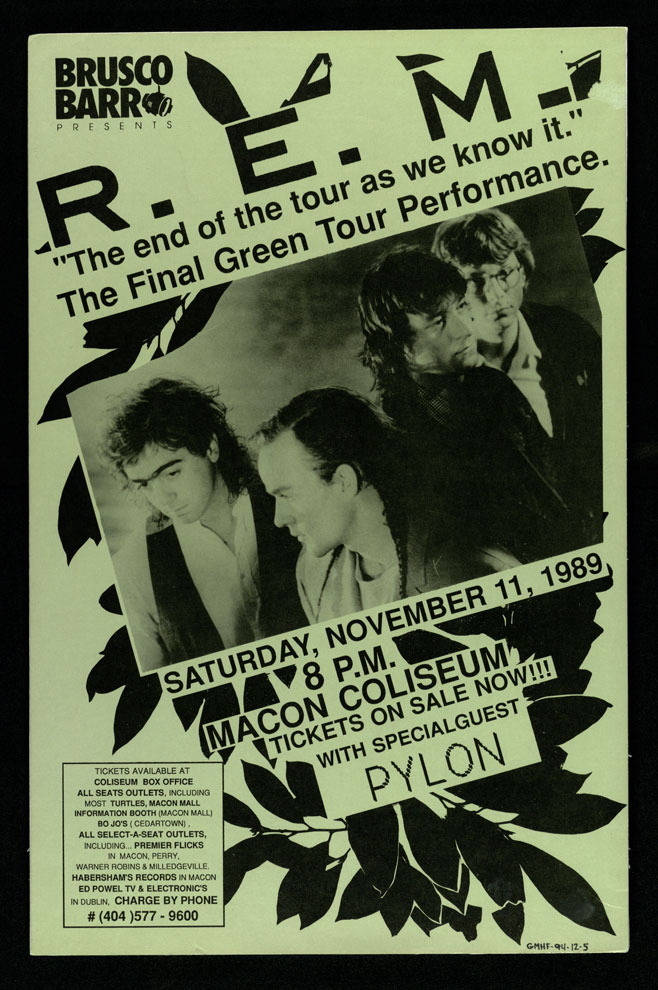

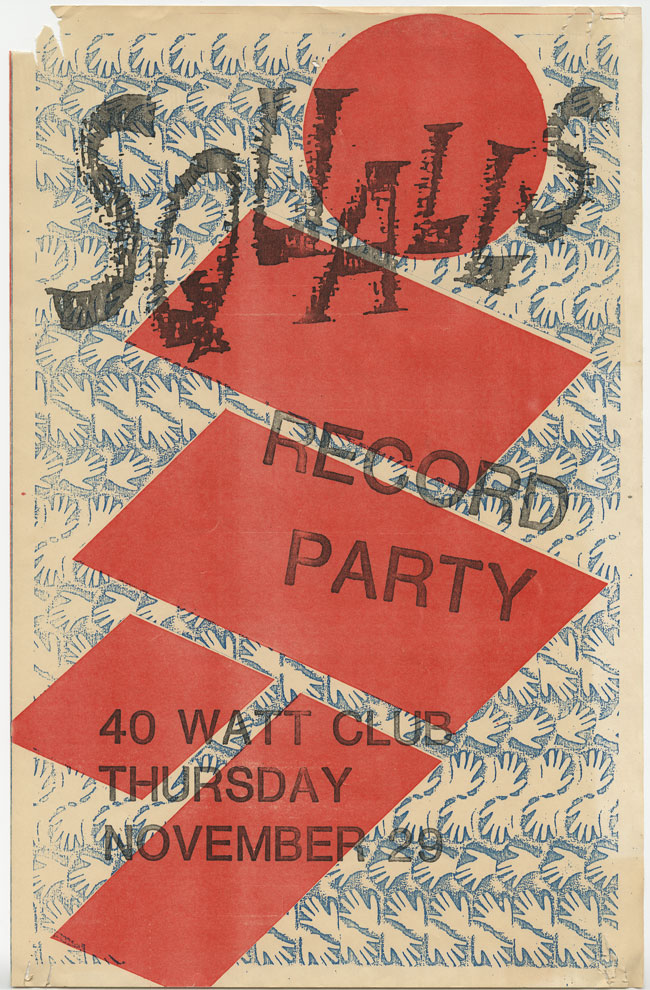

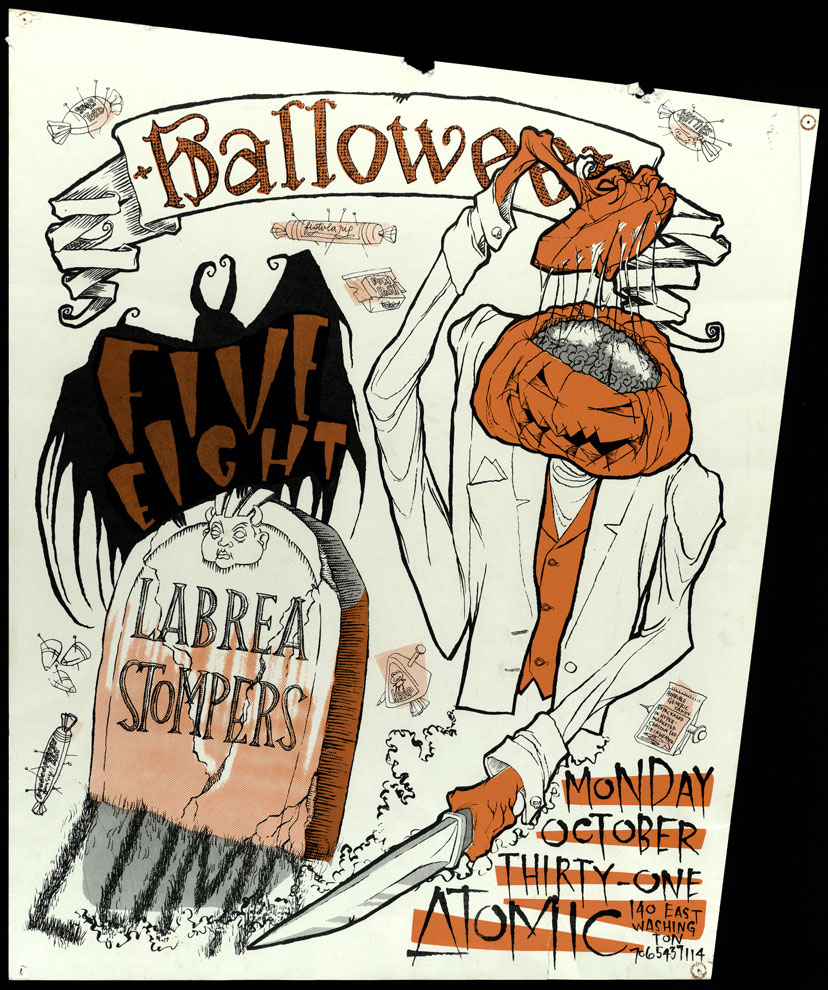

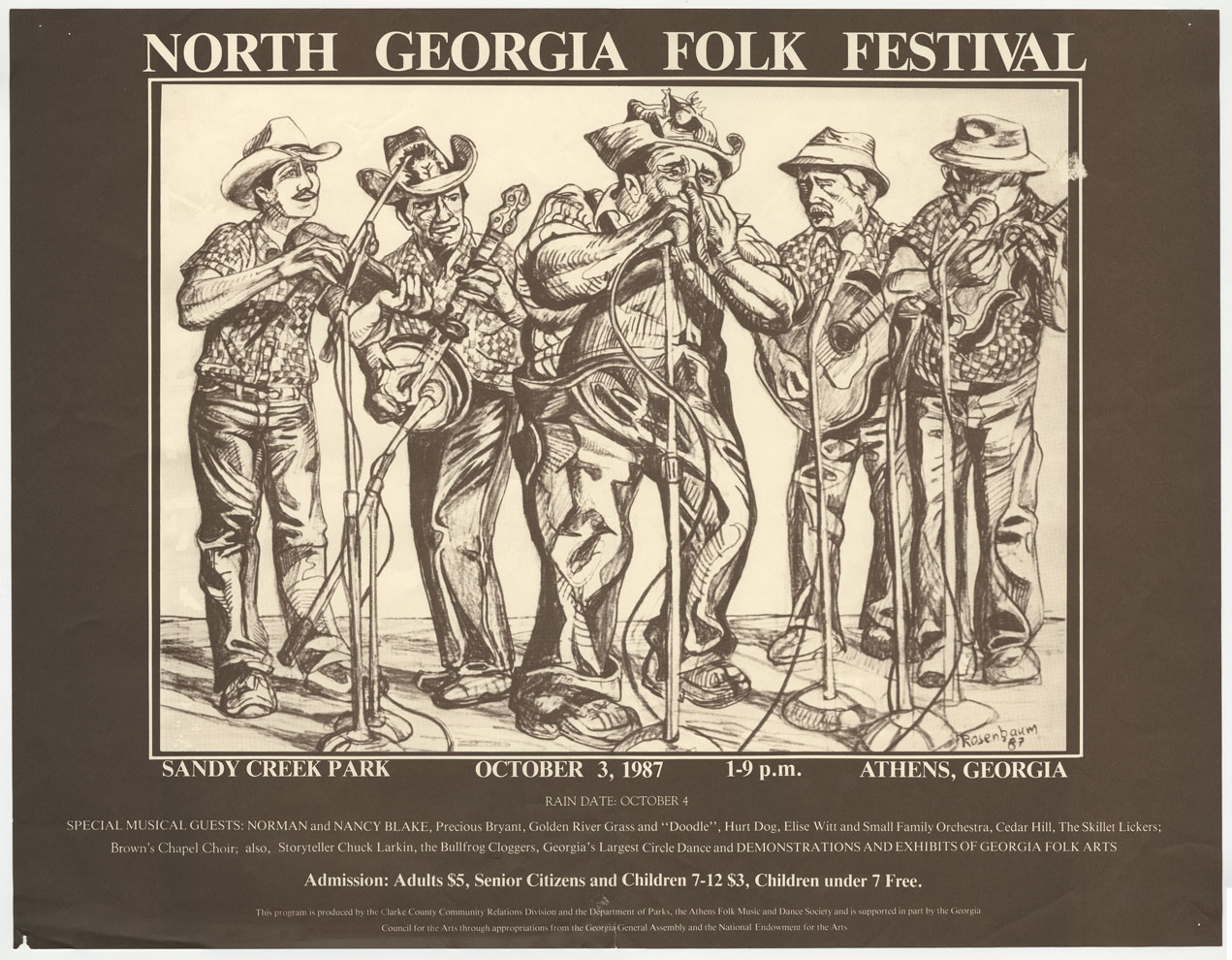

Though the current focus is on oral histories, those interviews are not the only artifacts of Athens’ music history that have found a home in the Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Other memorabilia, such as posters and playbills from concerts past, are also archived in the collections.

That is how UGA became the caretaker of Georgia music history, with virtually the entire Hall of Fame collection making its way to Athens as part of the Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library. It created, in Graham’s view, almost an obligation for the university to begin building ancillary collections around the transferred materials.

At about the same time, Kidula teamed up with fellow music professor Susan Thomas put together a proposal to the Willson Center for the Humanities and Art to do research, design curricula, conduct outreach, sponsor performance events—and collect materials—with a focus on Athens music of all genres.

So was born the original research cluster known as the Athens Music Project. What happened next, Kidula said, was a bit overwhelming.

“The project got publicized by the Willson Center, and we started getting emails, phone calls,” she recalled. “People had ephemera, archival stuff they wanted to give us. They were telling us about radio programs back in the day. I would meet people on the street, and they would say, ‘You look like the lady we saw in the paper with the Athens Music Project.’”

“Understanding why Athens has been able to connect to all these different scenes tells us something not just about Athens, but it tells us something about the larger history of music in this country that we can’t fully understand by just looking at major cities like Detroit or New Orleans,” said Thomas, now professor of musicology and director of the American Music Research Center at the University of Colorado. “These hyper-local histories are becoming more and more common, and they’re really important.”

As the relics of Athens history began to stream into Kidula’s and Thomas’ offices, they quickly realized they needed expert assistance. Once again, the initiative moved in harmony with the Libraries’ special collections, with Lopez helping the two music professors understand how such materials could be collected and archived. Lopez had also secured his own funding from the Georgia Music Foundation to produce oral histories from the musicians themselves.

“In my graduate class, the students actually went into the community, interviewed people and made audio and video recordings for them,” Kidula said. “I was co-teaching that class with Christian so the students could have a proper experience. I’m not an archivist and Christian is, and I am an ethnographer and he is not. He is an oral historian.”

“There was an incredible opportunity there,” Lopez said. “Jean and Susan knew oral history and knew the value of it. They knew it was absolutely critical when you’re doing ethnomusicology.”

Voices of history

From the beginning, Lopez’ contributions to the Athens Music Project were rooted in the community. Oral history at its best fills in gaps around the official record, illuminating the more personal aspects of the past, and Lopez knew the best way to put interview subjects at ease was to have them talk to familiar faces. Even better was to let the community itself drive the project.

“This was the kicker: We were going to get people in the community to decide and select themselves who they thought should be interviewed, rather than having academia come in and say, ‘We’re going to tell you who’s important in this scene,’” said Lopez, who’s also received support from a Whiting Foundation Public Engagement Seed Grant and (through the Willson Center) a Mellon Foundation Humanities Grant to unearth these oral histories.

One of Lopez’ first calls was to Knowa and Mokah-Jasmine Johnson, the husband and wife duo who’d recently relocated from Florida and quickly founded the Athens Hip Hop Awards. Lopez’ grant from the Georgia Music Foundation called for him to devote half his energies to African American music and the other half to the indie rock scene, so another early recruit was guitarist and longtime Athens resident Curtiss Pernice, who played with the late Vic Chesnutt and also co-founded the ’80s hardcore band Porn Orchard.

“We had made contact [through the Hip Hop Awards] with many artists and people from different generations who were doing music in this town. So we decided to start by interviewing the ones whose names came up often in the hip hop community,” Knowa Johnson said. “It was an honor.”

“By doing these interviews, I got to know Athens in a different way,” Mokah-Jasmine Johnson said. “The hip hop artists we chose to interview have seen and lived through the changes of Athens’ music scene. It was good to hear their personal stories. We learned things you probably wouldn’t know unless you knew a friend or a family member.”

Montu Miller was another veteran of the Athens hip hop scene who joined the project. Miller recalled an interview with Athens hip hop artist Billy D. Brell, who shared his own history as well as the family stories he knew and heard about growing up in Athens.

“He had an uncle who had this juke joint on the east side, off the road but everybody knew about it. Even the famous people who came to Athens went there,” Miller said. “It was in the back of his family’s house, and they used to just rock all night. I learned a lot from him.”

Not only interview subjects but also interview locations were left largely up to the interviewers. Miller preferred to do his interviews at Ciné downtown, while Pernice opted for different settings, including the back porch of his house on a hot summer night with cricket song as backup vocals. Lopez provided technical training on audio equipment to help interviewers capture the best possible sound, as well as some instruction on proper interview technique for oral history.

“Wherever the conversation turns is legitimate,” recalled Pernice of his crash course in oral history methodology. “I would say to people, ‘This is just going to be like if we ran into each other at a show and started talking.’ A lot of it turns into you talking about your guitars or your gear, or even a van someone had when they were touring and it broke down, and then that turns into a story. Anything that’s related to music or their experience with it is valid. Even with people I’ve known forever, I always learn something new.”

This spring, Lopez is leveraging the Athens Music Project to help UGA students learn something new. He and Senior Lecturer Montgomery Wolf from the Department of History are co-teaching a course on oral history methods and theory to a class of undergrads and graduate students. For the course practicum, its two undergraduates will do oral history interviews with the staff members of Nuçi’s Space, a local health and resource center founded specifically to support Athens musicians and their mental health needs.

“I have a passion for both journalism and history and thought this was such a fascinating intersection of both subjects,” said Rachel Priest, a senior journalism major in the course. “One of my favorite parts of being a journalist is getting to interview the subjects and learn what they’re passionate about. I’m excited to hear some of the ways in which Nuçi’s Space has impacted members of the Athens music community, and I’m glad their interviews will be accessible to other historians and future journalists.”

Building bridges

As historical artifacts and oral history recordings accumulated, and the Athens Music Project began to generate a rich catalog of resources for the hyperlocal music ethnographer or enthusiast, both Kidula and Lopez realized something else was happening. This effort, originally intended to shed light on experiences and histories buried in the past, was beginning to have a positive influence on the present.

“For a very long time, the only Athens music scene that was popularized were people who were white,” Lopez said. “There was a hip hop scene, a rap scene that was going on, a gospel scene. There were the sacred and secular music scenes, and thank goodness we have some of those collections, but those things were unrecognized. We had a wealth of a certain kind of history and a dearth of information about these other communities.

“The oral histories were, to me, a way to begin to change that,” he said. “Slowly, certainly—but it was a start.”

“One thing I think it’s doing is helping to build bridges,” Miller said. “I would say ‘rebuild,’ but I feel the bridges never really got built. They got started, and this is helping to build that bridge some more.”

“The footprints of African Americans fell here, but nobody really talked about them,” said Kidula, who recalled a special experience from one of the “Night at the Morton” shows, organized as part of the Athens Music Project’s first life, that showed the kind of impact this work can have.

The Morton Theatre, founded in 1910 by Monroe “Pink” Morton, one of Athens’ most prominent African American businessmen, became a regular stop for black musicians touring the South prior to desegregation. These venues became known as the Chitlin’ Circuit, and such legends as Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway, Bessie Smith and Louis Armstrong all performed at the Morton during its heyday.

Beginning in 2016, Kidula and Thomas worked with an array of UGA offices and programs to hold gala concerts at the Morton that were intended not only to showcase African American music but also bring together a rich mixture of both artist and audience member, with older performers sharing the stage with younger, in front of crowds that reflected this diversity.

The last Night at the Morton show was held in March 2018. One of the performers was Ansley Stewart, a professional vocalist who grew up in Athens. Stewart, who is white, began to sing “I Never Loved a Man,” by the Queen of Soul herself, Aretha Franklin (who would pass away just five months later).

“When she started singing, people listened, and then they started singing,” Kidula said. “And she was accompanied by a black blues musician from Athens. And people were singing, and you could hear the black voices, and the white voices, and everyone was singing together.

“Her piece brought the house down.”