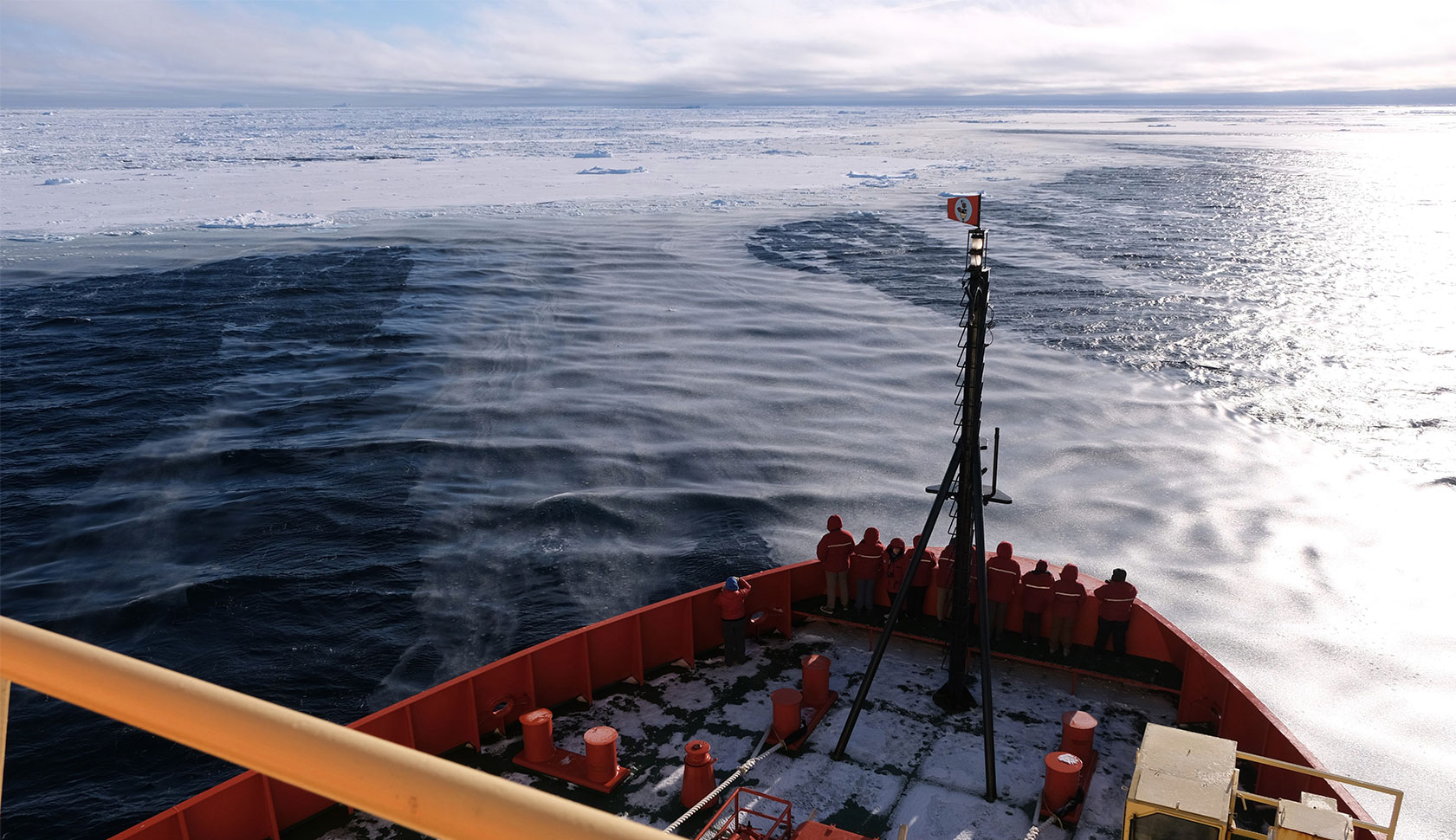

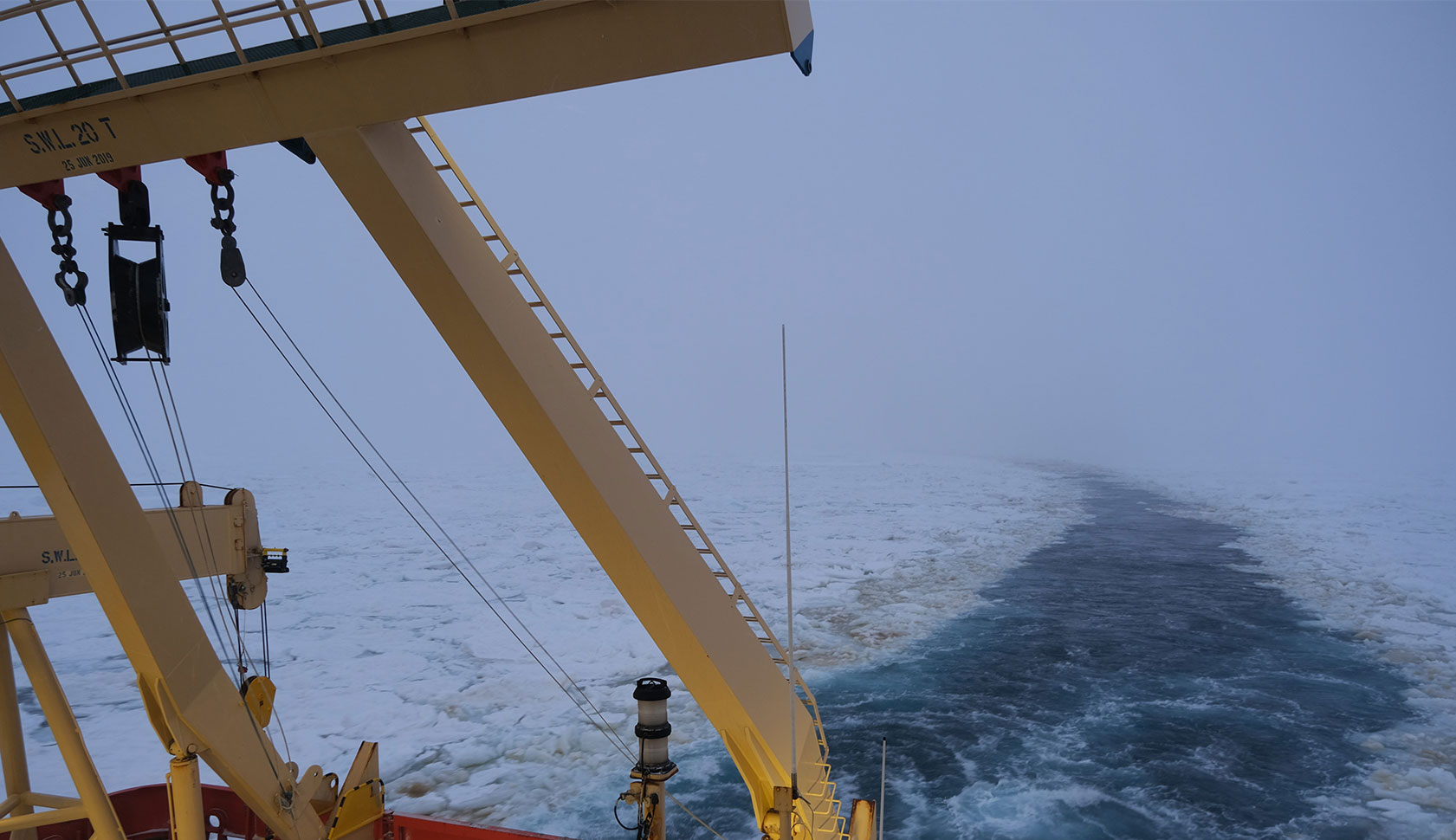

The permanently frozen coastline was wrapped in endless expanses of glaring white ice shelves, towering fields of icebergs floating away into the blue-black sea. The landscape was lonely and cold, the weeklong journey south from New Zealand tortuous and humbling.

East Antarctica is one of the most remote regions of our planet, and the vast distances conjured a new respect for geographic scale and the relative size of more diminutive human bodies.

From February to May this year, Holly Bik led a group of researchers from the Franklin College of Arts and Sciences Department of Marine Sciences on this frigid voyage aboard the Nathanial B. Palmer for 48 days, traveling where no U.S. research vessel had gone in 22 years.

They were searching the seafloor for marine nematodes—microscopic roundworms that live by the thousands in every handful of sand and soil on Earth. Without a microscope, they are no larger than specks of dust, but understanding the way they live helps us understand how ecosystems work.

The Antarctic continental shelf’s environment resembles the deep sea when it comes to temperature and the amount of sunlight it receives, making it the only place in the world where deep-sea communities can live in relatively shallow waters. In other ecosystems, natural patterns may be explained by environmental differences between sampling spots. Having similar environmental conditions in different Antarctic locations, however, makes clear how evolution influences nematode communities.

Bik’s discoveries about the evolution of Antarctic worms can teach scientists about unique species only found in the Southern Ocean. The genomes of Antarctic invertebrates can help pinpoint adaptations to polar ecosystems, as well as help evaluate how organisms all over the world may demonstrate resilience to climate change.

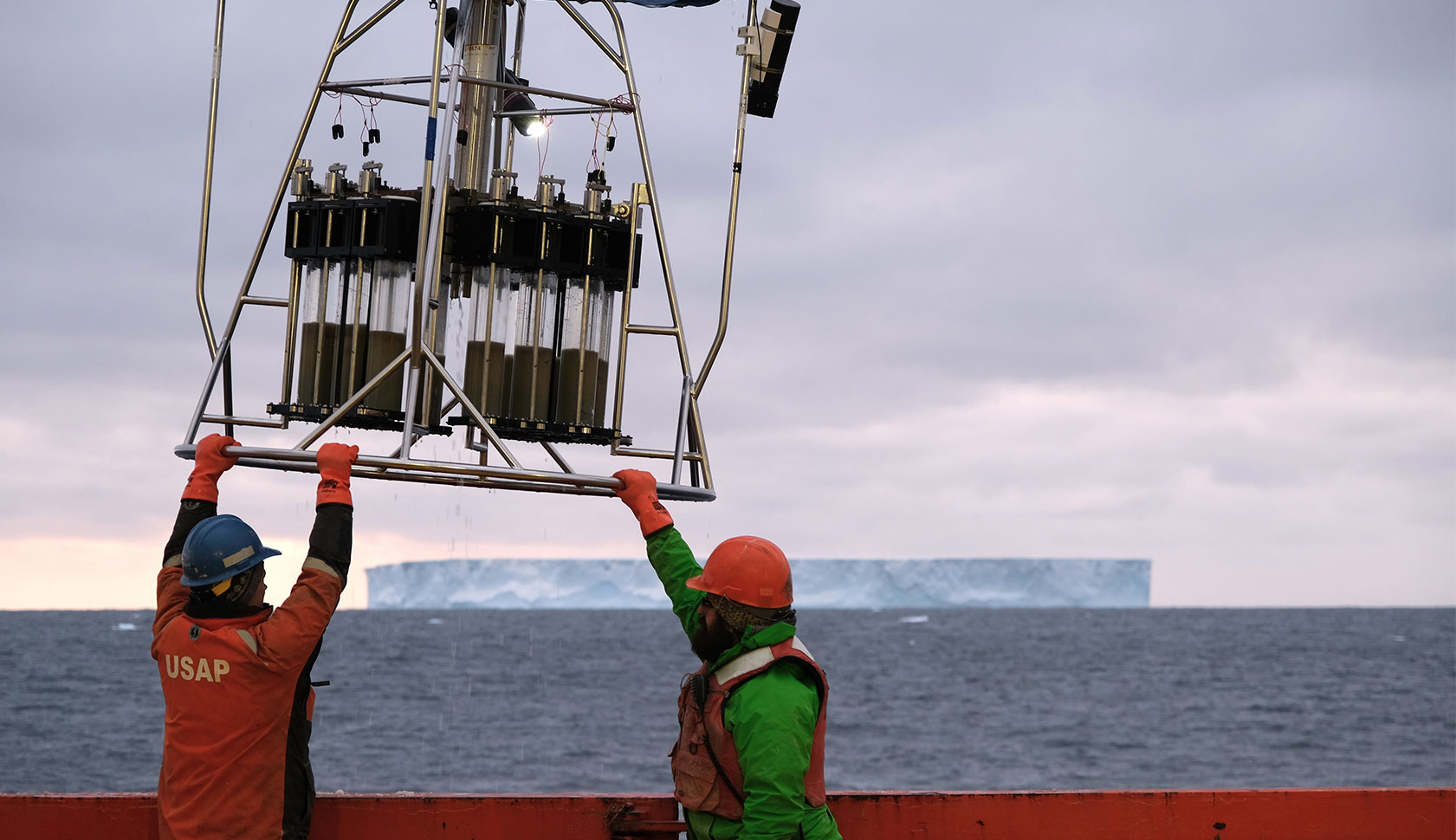

The team was composed of postdoctoral scholar Tiago Pereira, doctoral students Mirayana Barros and Alejandro De Santiago, and science media specialist Virginia Schutte. They worked in 12-hour shifts that allowed for 24-hour operations, so that someone was always ready to grab and process mud as it rose from the seafloor.

Though the team disembarked in early May, they didn’t receive frozen mud samples until late August and don’t expect room-temperature samples to arrive in Georgia for several months. Bik hopes to describe at least 100 new nematode species from the expedition.

Bik is anxious to see results but expects it will be late next year before all samples are processed.

“Our Antarctic samples may look like messy plastic bags full of brown mud, but these samples are really special,” she said. “I’ve been waiting over a decade to have the opportunity to collect my own Antarctic seafloor samples, and I’m so excited to explore the incredible biodiversity of these Antarctic nematode species.”

The work is supported through an award from the National Science Foundation Office of Polar Programs.