While recycling is often touted as the solution to the large-scale production of plastic waste, upwards of half of the plastic waste intended for recycling is exported from higher income countries to other nations, with China historically taking the largest share.

But in 2017, China passed its “National Sword” policy, which permanently bans the import of non-industrial plastic waste as of January 2018. Now, scientists from UGA have calculated the potential global impact of this legislation and how it might affect efforts to reduce the amount of plastic waste entering the world’s landfills and natural environment. They published their findings in the journal Science Advances.

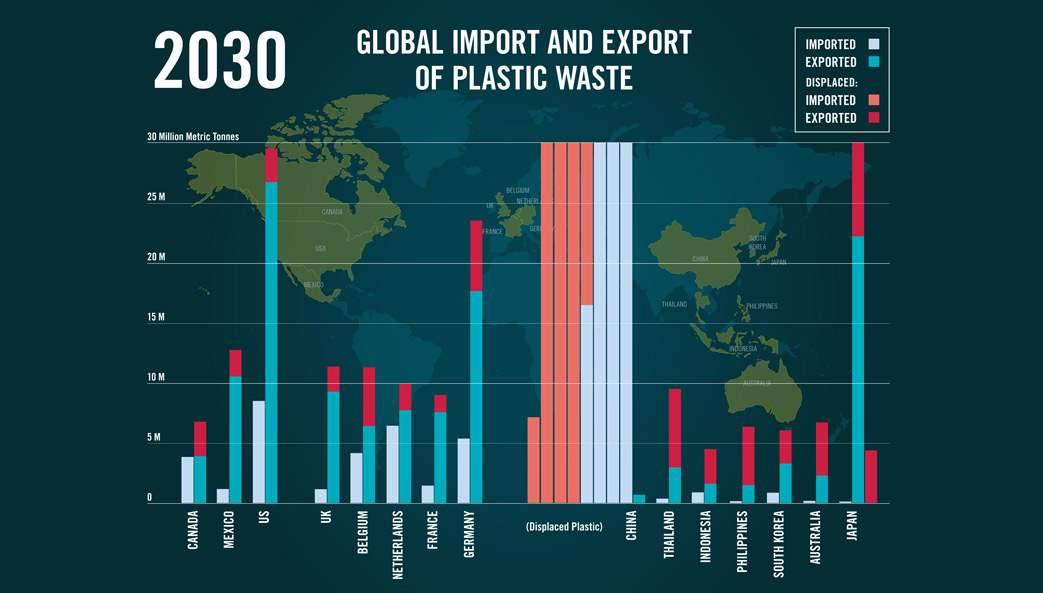

“We know from our previous studies that only 9 percent of all plastic ever produced has been recycled, and the majority of it ends up in landfills or the natural environment,” says Jenna Jambeck, associate professor in UGA’s College of Engineering and co-author of the study. “About 111 million metric tons of plastic waste is going to be displaced because of the import ban through 2030, so we’re going to have to develop more robust recycling programs domestically and rethink the use and design of plastic products if we want to deal with this waste responsibly.”

Global annual imports and exports of plastic waste skyrocketed in 1993, growing by about 800 percent through 2016.

Since reporting began in 1992, China has accepted about 106 million metric tons of plastic waste, which accounts for nearly half of the world’s plastic waste imports. China and Hong Kong have imported more than 72 percent of all plastic waste, but most of the waste that enters Hong Kong—about 63 percent—is exported to China.

High income countries in Europe, Asia and the Americas account for more than 85 percent of all global plastic waste exports. Taken collectively, the European Union is the top exporter.

“Plastic waste was once a fairly profitable business for China, because they could use or resell the recycled plastic waste,” says Amy Brooks, a doctoral student in engineering and lead author of the paper. “But a lot of the plastic China received in recent years was poor quality, and it became difficult to turn a profit. China is also producing more plastic waste domestically, so it doesn’t have to rely on other nations for the material.”

For exporters, cheap processing fees in China meant that shipping waste overseas was less expensive than transporting the materials domestically via truck or rail, according to Brooks.

“It’s hard to predict what will happen to the plastic waste that was once destined for Chinese processing facilities,” Jambeck says. “Some of it could be diverted to other countries, but most of them lack the infrastructure to manage their own waste, let alone the waste produced by the rest of the world.”

The import of plastic waste to China contributed an additional 10 to 13 percent of plastic waste, on top of what they were already having a difficult time managing, because of rapid economic growth before the import ban took effect, she says.

“Without bold new ideas and system-wide changes, even the relatively low current recycling rates will no longer be met, and our previously recycled materials could now end up in landfills,” Jambeck says.

This story appeared in the fall 2018 issue of Research Magazine. The original press release is available at https://news.uga.edu/scientists-calculate-impact-of-chinas-ban-on-plastic-waste-imports/.