Editor’s note: From February to May 2023, Associate Professor Holly Bik led a group of researchers from the Franklin College of Arts and Sciences Department of Marine Sciences on a frigid voyage to Antarctica aboard the R/V Nathanial B. Palmer for 48 days, traversing a location no U.S. research vessel had gone in 22 years. They were searching the seafloor for marine nematodes—microscopic roundworms that live by the thousands in every handful of sand and soil on Earth.

While the following are not actual journal entries written aboard the ship, they are real stories from real researchers that capture life on the frozen seas. Featured stories are provided by Mirayana Marcelino Barros, Holly Bik, Tiago José Pereira, Alejandro De Santiago Perez, and Virginia Schutte. After an extended quarantine period, ensuring safety through the lingering impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, the researchers boarded the ship on March 19, 2023. (Story and illustrations by Virginia Schutte)

March 19: Port Lyttleton, New Zealand

After spending weeks in New Zealand quarantining, we have finally set foot on the ship! This is my first research cruise, so I am really nervous and do not know what to expect. But I am so excited to finally be getting started.

We stayed in the center of town for a few days after flying down, giving us time to get over the jetlag and line up logistics like getting fitted for our cold weather gear. With COVID protocols, we’ve been wearing masks and isolating. It felt weirdly obvious that we’re not on vacation.

But on our scheduled boarding day, a few of the 65 or so people on the ship tested positive. So, instead of getting onboard, we moved to a hotel by the airport, very close to the Antarctic program facilities. We stayed there for a week, during which more people tested positive and isolation protocols increased. The scientists on this cruise don’t know each other, so we’ve been meeting by giving short research talks on Zoom and hanging out while socially distanced outside, in the hotel courtyard.

We’ve also been playing a game to try and use up all the drink tickets the hotel has been giving us. We get one with lunch and one with dinner. We’ve been here so long, and not letting them go to waste with the last-minute call to finally get on the ship at 10 p.m. was fun.

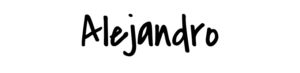

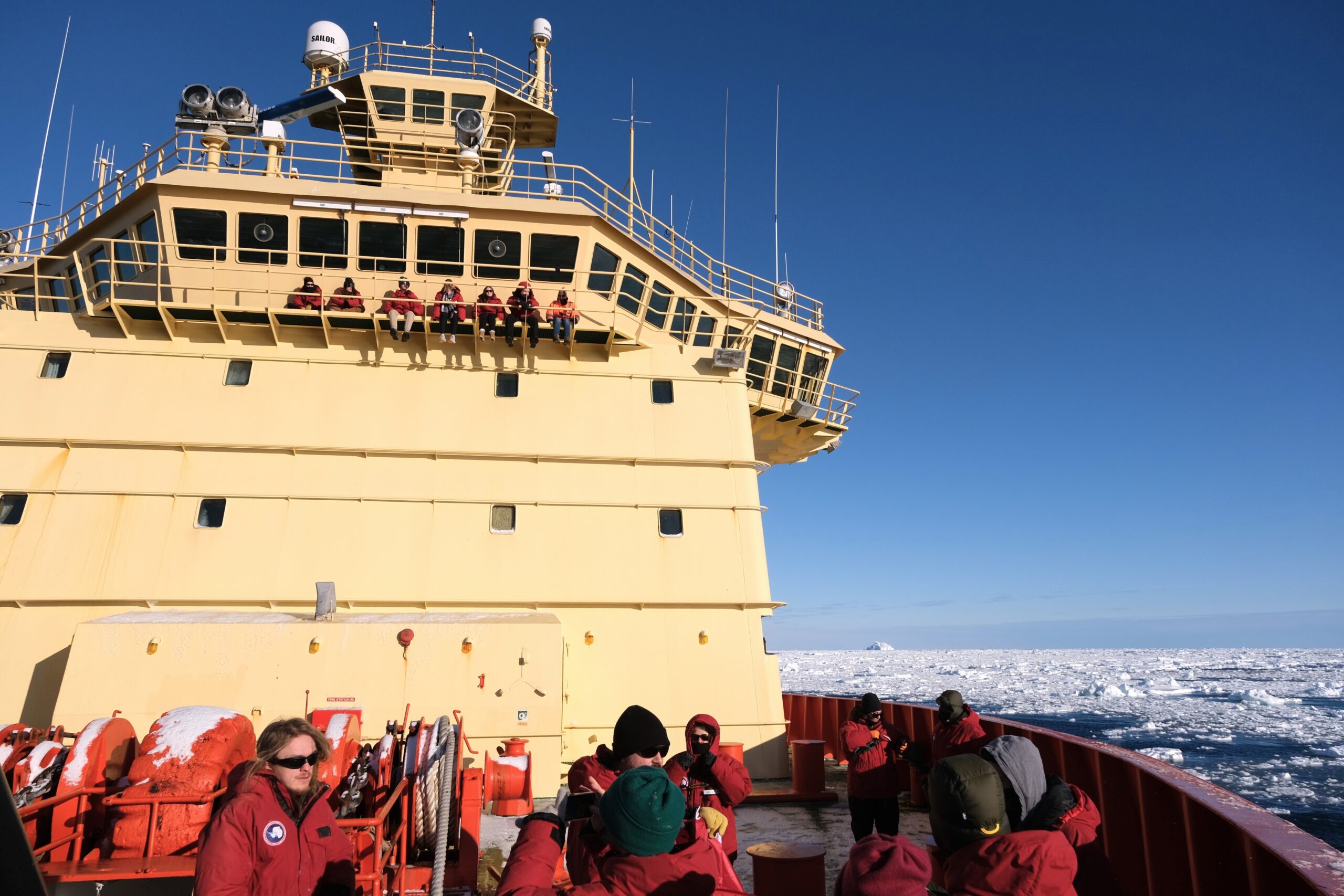

April 2: The end of the 10-day Southern Ocean crossing

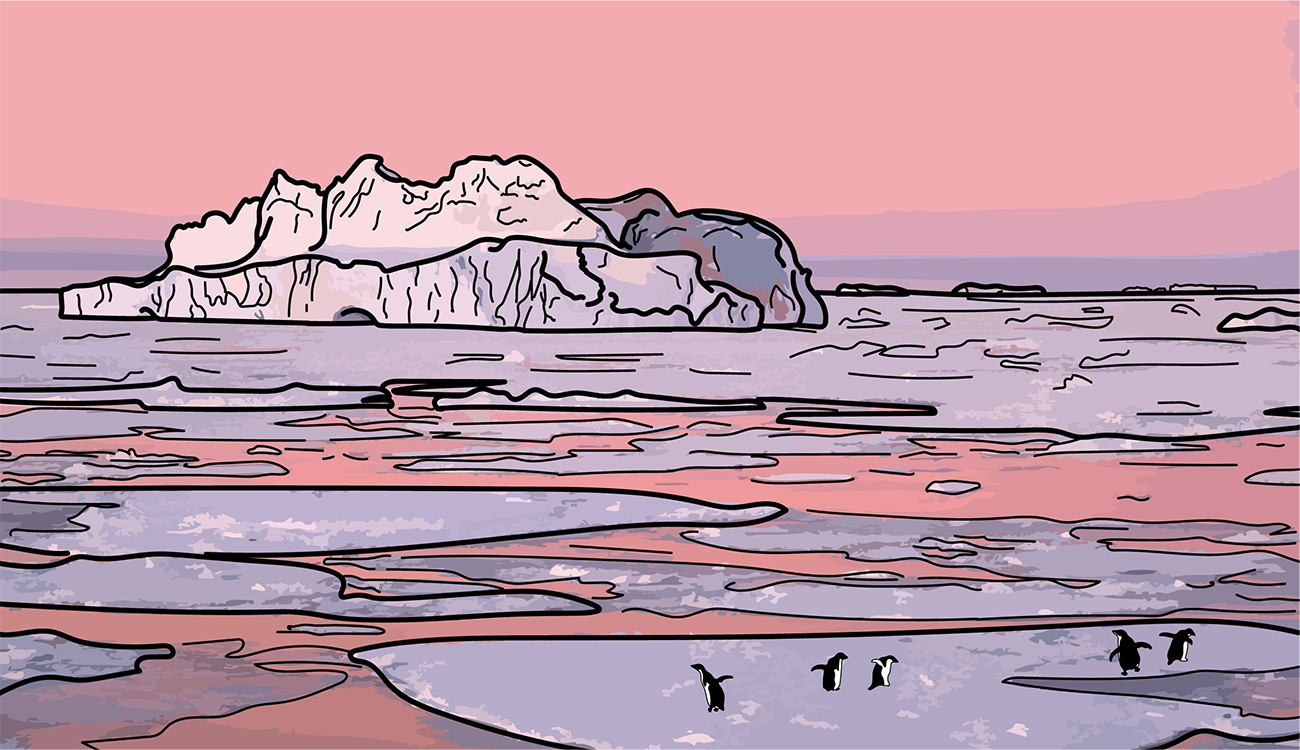

The day broke clear and sharp, with a sun bright enough to make you feel like you’d woken up in the first chapter of some great, untold adventure. The sea stretched empty and calm around us, as if holding its breath. And then, there it was: a single white fleck on the horizon, our first iceberg. We practically tripped over each other to get on deck, bundled up like Antarctic explorers but darting in and out of the ship because the cold was biting, even with the sun. That lonely ‘berg lingered on the horizon as we steamed forward. Then, just like that, mid-morning arrived, and we were surrounded by an entire flotilla of silent, gleaming icebergs. Solitary, yet gathered together, they drifted by us in icy companionship.

When I first spotted that small white dot, I was like a kid on Christmas morning, thrilled even from a distance. But by lunchtime, I realized I had gotten excited too soon. Seeing these icebergs up close was something else entirely: they were enormous, textured, and full of hidden caves and rugged peaks. And the colors! The water around them was so clear you could see into that deep spectrum of blue, from frosty white to electric turquoise. Each one was a masterpiece of ice and light, like natural sculptures carved by time and the sea.

Eager to capture the perfect shot, I braved the deck with my camera. Determined, I took off my gloves for “just a minute” to adjust the settings—a rookie mistake, of course. Within moments, my right thumb went numb, turning a shade of purple. I quickly went back inside to warm up, my thumb was hurting pretty bad for a while. For a few minutes there, I could picture myself without a thumb, nursing what felt like the beginnings of frostbite. I almost lost my thumb, but hey, I got the stunning shot (a true explorer’s sacrifice!)

Out here, in this massive, frozen expanse, I feel so small—a tiny speck in a boundless, icy world.

April 5: Still headed south, but we’re turning west now

I hate exercising on the ship. I just want to spend my time looking out the windows or walking the bridge, hunting for spectacular photos and videos. The gym has no windows, and the only thing that really gets my heartrate up is the treadmill. But any time the ship rocks, even a little, the treadmill becomes an arm workout because I have to hold myself in place using the handrails.

Except that I just found the most incredible workout routine. I start on the port side of the ship, on the lowest outside deck (01). From there, I can go up a flight of stairs, along the 02 deck, up another flight of stairs, across and along the 03 deck, and up two flights of stairs. Then I run as far back on the bridge level as I can, slap the railing, and come back to the stern door of the bridge. Then it’s over to the starboard side of the ship, where I go down a set of stairs, run the length of the 04 deck, and go down half a level to where the lifeboat blocks my route. Then I repeat the whole up-and-over routine, going back the way I came. Seven of those complete laps (returning me to the spot where I started) gets me through 30 minutes of exercise.

The air at home is so heavy and humid. But the air in Antarctica is so dry I can’t even smell the ocean. I feel so optimistic when I’m on deck, like I am strong enough to be ready to meet any challenge that might come my way on this expedition.

I think this will be a short-lived routine, because the ship has to be stable and as soon as it snows the deck will get too icy for this to be safe. But I will do this every day until the weather (or someone on the ship) makes me stop.

April 10: A week into science sampling

All our modern technology is kind of useless down here!

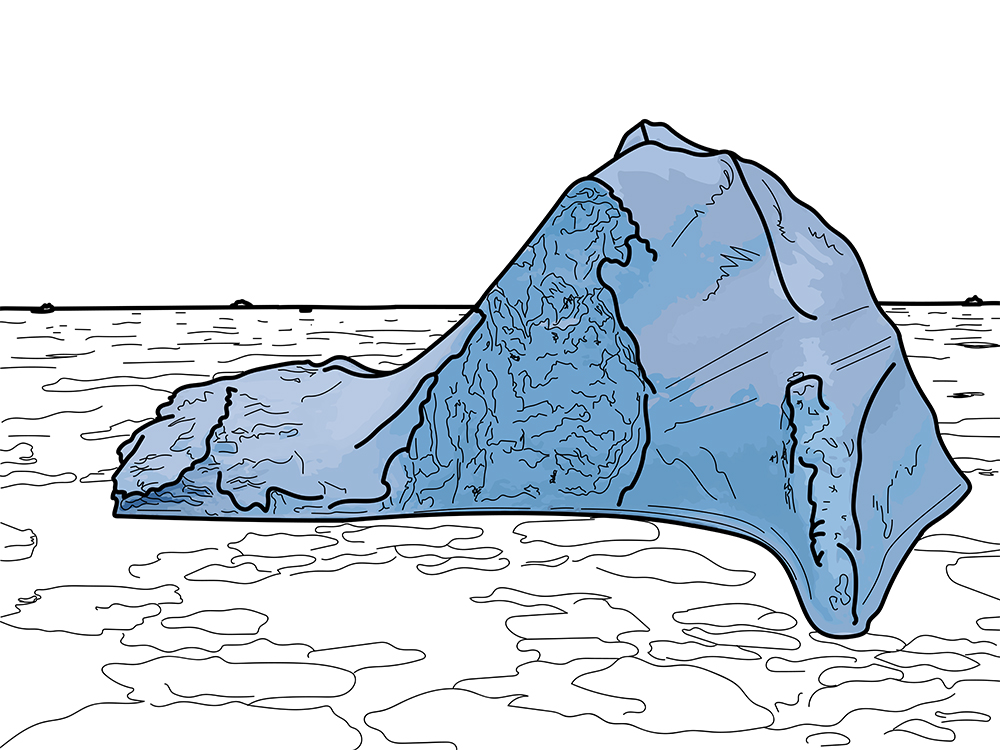

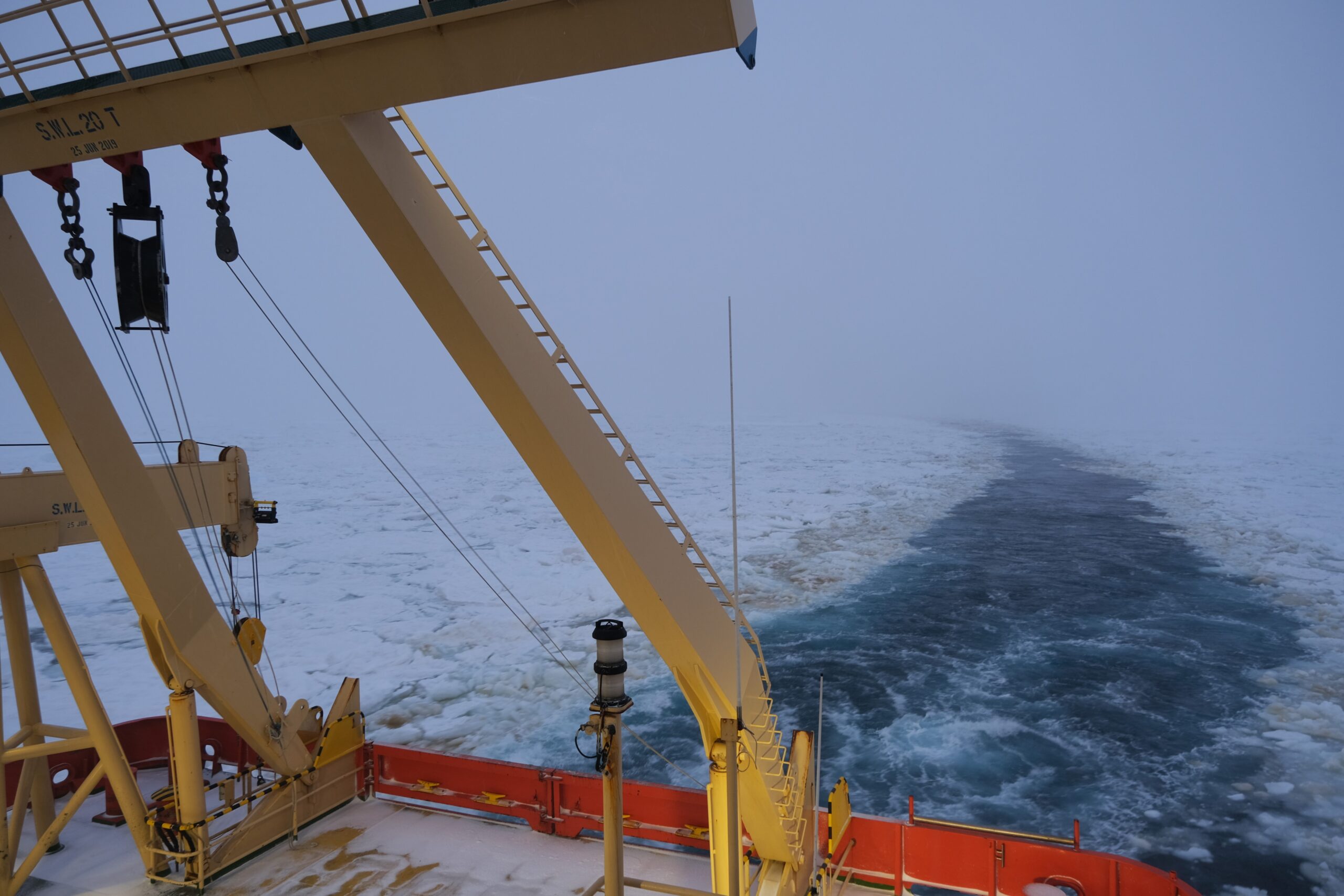

Every morning the captain gets a call from a company with satellites taking pictures of the ice around Antarctica. Those pictures were taken about 48 hours ago and then passed on to people who manually draw lines around what they think are clustered areas with different types of ice, noting where different types of ice could be. By the time these maps reach us, it’s old and the ice has already moved.

So, the captain, pilots, and crew mostly rely on their eyes to assess current ice conditions and make quick navigation decisions without the aid of maps, radar, etc., like they would in other parts of the ocean. I see the captain on the bridge, often with binoculars in hand, speaking with the pilot on duty at the time. Their immense knowledge about ice conditions and weather patterns is incredible.

April 16: Settling into a science routine

I expected it to be challenging to work and sample in these conditions, but it’s way more difficult than I thought. Working in such a remote region, where the landscape shifts daily and the ship relies on morning ice coverage data to move around, makes things much more complicated and slower than anywhere else I’ve ever sampled. We’ve had many situations now where sampling stations were not too far from each other and the expected travel time between them was only a couple of hours. But that turned into eight to 10 hours because of sea surface conditions (mainly the thickness of the ice).

Instead of just working my shift, I’m really on call during my shift hours. I wake up and check the feeds on my cabin TV, one of which shows the computer-screen map of where we’re going and where we’ve been. Most importantly, that map shows the line we’ve traveled up to this point. If that line is straight, we’re making good time, and I know our on-station arrival time estimate might be somewhat reliable. Often, that line makes no sense against the backdrop of the plain map, so I know we’re going around thick or dangerous ice.

April 17: Bouncing west, north of the Antarctic coast

Our dishwasher at home had a catastrophic water leak!

There was water all over the kitchen and my husband, who is alone with the 2-year-old and 8-month-old, had to clean it up. He is trying to find a repair person—while doing dishes by hand now, of course!

I’ve been calling him every day, sometimes using the satellite phone in the project coordinator’s office so I don’t use all the morale phone time downstairs. We’re about 12 hours offset now because we’ve traveled so far west, so he emails me further updates while I’m asleep and I write him sometimes when he’s out too.

The only time we are both awake is 9 a.m., so that’s my time to talk live about this emergency!

April 20: We are always going west now

I’ve settled into a morning routine that starts the night before. After dinner, I go back to my cabin to put on cozy clothes, grab my nighttime tea, and pick out my clothes for the next day. I pile those on my section of the cabin desk, being careful not to disturb Holly’s side. I have an alarm set for 6 a.m. but if I wake up after 5, I’m allowed to get out of bed. If it’s before 5 a.m., I’m supposed to make myself to back to sleep. But there’s a whole night shift playing games or doing work, and it’s just so annoying to have to miss it.

Holly doesn’t wake until later, so I grab my clothes pile off the desk and sneak into the bathroom to get dressed. I’ve got a few hours until breakfast, so I make tea and check where we are in the sampling cycle. Are we in transit or stopped? If we’re stopped, where are we in the cascade of sampling events? Which team is on the back deck or on call waiting for their stuff to come up?

After breakfast, I head back up to our cabin to finish getting ready. I wash my face, then brush my teeth in front of the porthole so I continue to not miss anything. I’ve so far seen many penguins, seals lounging on ice floes, and even a few whales during my tooth-brushing time.

April 22: Working so far south we’re in view of the continent

My work shift has become midnight to noon. I think I see as much light as the noon to midnight crew, because the sun is coming up so early.

Last night the Megacore came up with our seafloor samples around 2 a.m. We have to take the tubes off the lander, which is a very wet job, and then we push the mud out of the tubes like a push pop, taking slices as we go to tell us what’s happening at precise depths.

Even though we were slicing inside the ship—technically, with a door open to the back deck but otherwise sheltered—washing cores and dealing with the cold water was particularly challenging tonight. The temperature was lower than usual, and we had stronger winds. The trawl crew said the wind was blowing off the continent and dropping temperatures to about 50 below. They had to cut their sampling short because the buckets of water were freezing before they could sort animals out of the mud and into those buckets.

Cooling the ship’s engine provides us with as much really hot water as we want. Nothing like a warm shower after the work shift ends. Dry clothes (and double socks) are key.

April 26: As far west as we’ll get, near to packing it all up for the 10-day crossing to Australia

I brought along a chessboard, a deck of cards, and a book—Women Who Run With the Wolves—as well as a collection of movies and series specifically downloaded for this trip. I planned to rewatch Game of Thrones in full, dive into the new House of Dragons release, and indulge in some classics, from Dirty Dancing and The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou to Braveheart. Funny enough, I never touched the chessboard, the cards stayed buried in my drawer, and I didn’t make it past the prologue of the book. Turns out, I haven’t had much time for any of that.

Most of my time is spent under the stereoscope, lost in the thrill of tracking down nematodes in our mud samples (which is entertainment for me!). And before I know it, it’s time to slice cores again. The movies and series come in handy during downtime, as I wait for samples to come up from the seafloor, usually with a few snacks I sneak from the galley as my guilty companion.

Working under the scope at sea has been an unexpected joy and a delightful surprise. Usually, ship conditions force us to freeze or store samples as quickly as possible, saving microscope work for later in the lab. But here in Antarctica, the ice dampens the swell, keeping the ship steady enough that I can safely and enjoyably observe samples in real-time. There’s an indescribable thrill in seeing what lies thousands of feet below us, right as it arrives, and noticing the unique character of these samples compared to sites I’ve explored before. It’s like peering into a secret world, with every glance a small discovery.

May 1: Somewhere south of Perth

My favorite part of this trip was being constantly surrounded by so many scientists.

Going into grad school during COVID was very difficult, especially since I wasn’t able to go to conferences. With lockdowns, I was doing science alone, and that’s just not what’s typical. I feel like my enthusiasm for this work had gradually fallen.

Being here, on this ship, surrounded by so many scientists who are excited by everything they see, has brought that enthusiasm back.

I’m ready to go home and begin working on my dissertation again. Hopefully, it’ll feel a lot better this time.