Whether negotiating whitewater rapids in her kayak, taking an early-morning swim across a lake or hiking beside a mountain stream, Laurie Fowler has always been at home in or near the water. So it was no surprise when she graduated from the UGA School of Law in 1983 that her goal was to use what she’d learned to protect Georgia’s rivers, lakes and wetlands.

Today, as co-director of the UGA’s River Basin Center, faculty member in the Odum School of Ecology and adjunct faculty member in the School of Law, her goal hasn’t changed—but as the issues affecting water and the laws designed to deal with them have evolved, so has her approach.

In 1983, the nation’s major environmental laws were still new, and many of the details of their intent and enforcement were murky.

“State and federal agencies in many cases lacked the resources to compel compliance with laws like the Clean Water Act,” Fowler said. “And it wasn’t always clear that the regulations the agencies had enacted were really what the Congress intended. There were a lot of public interest lawsuits—and I was involved with some of them—to clarify that.”

Early regulations focused on reining in “point source” pollution—the kind that comes from an identifiable outlet such as a factory smokestack or sewage pipe. And although regulations proved increasingly successful in achieving that goal, that still left a major type of pollution essentially unrestricted: the nonpoint source pollution that comes from many places at once and for which no single entity is responsible.

As a law student, Fowler had sought out Eugene Odum, then the director of UGA’s Institute of Ecology, to learn about the science of ecology to complement what she was learning about environmental law.

“Even then, Dr. Odum was telling me that what was going to become more important was looking at and addressing what was happening on the land—looking at the volume and contents of stormwater nonpoint source pollution, for example—to protect water quality,” she said. “And today it’s acknowledged that nonpoint sources of pollution outweigh point source pollution in both volume and impact in many communities.”

Fowler believed that science-based policy development, planning and land conservation could be far more effective against such a decentralized threat. To put these ideas into practice, she returned to UGA and established the environmental practicum. This program brings together graduate students from law, ecology and other fields to solve real-world problems for local governments, state agencies and nonprofits. In 2003, she became co-director for policy of the River Basin Center, which draws faculty and students from across campus to work on sustainable management of aquatic resources and ecosystems through applied scientific and policy research.

Fowler and her students and colleagues have been at the forefront of researching and communicating the scientific and legal underpinnings of land conservation and planning tools to protect water quality. Their findings inform state laws and local ordinances and are used by agencies like the Georgia Department of Natural Resources, Metro North Georgia Water Planning District and Department of Community Affairs.

Over time, the nature of the environmental problems Fowler grapples with have changed, and so has the legal landscape for addressing them.

She points in particular to recent Supreme Court decisions. These rulings, she said, require environmental rule-makers to produce more scientific evidence to show that each new regulation “is actually a legitimate way to go about addressing the problem.”

Fowler believes that this new legal landscape for environmental regulations increases the relevance of the River Basin Center and similar institutions. “We are addressing both the scientific justification and developing the policy that will most effectively achieve what the science says we need to achieve to protect the resource,” she said.

One of the recent problems that Fowler has tackled—water availability—was not even on the horizon when she started her career.

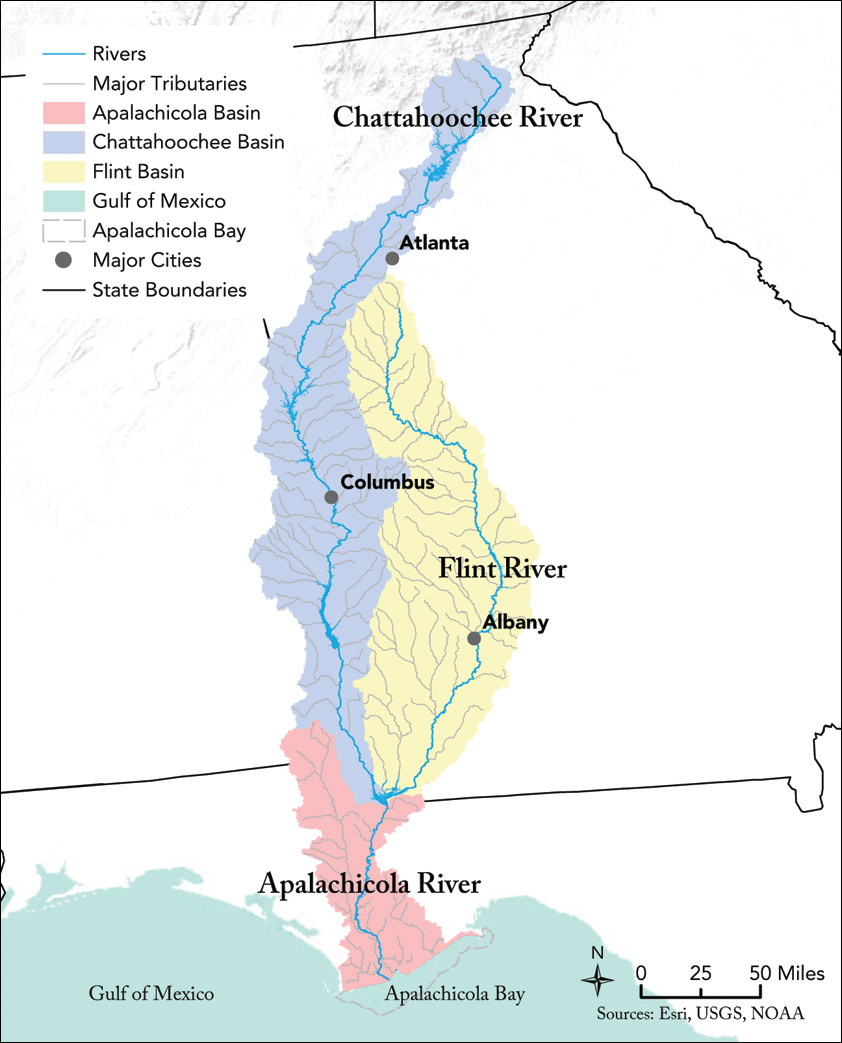

In 2014, a group of municipalities, power companies and environmental advocacy organizations in the Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint watershed asked Fowler and the River Basin Center for help. Frustrated with the lack of progress in the long-running dispute between Georgia, Florida and Alabama, they wanted to create a water management plan and an institutional framework for administering it. Fowler organized a consortium of institutions from the three states to identify strategies for sustainable trans-boundary management, which the stakeholders group is now working toward implementing.

Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint River Water Basin

Finally, Fowler said, the need for meaningful stakeholder input and communication with the public has become more critical than ever.

“We are all nonpoint polluters, and we need to make sure our personal actions don’t contribute to the problem,” she said. “We have to support local government in their efforts to control pollution through land use planning, regulation, incentives and paying for infrastructure through property taxes, local sales taxes and user fees. That means we have to make sure the regulated community can live with these strategies.”

That’s why Fowler is excited about two new programs she recently helped start. One is a bachelor of arts in ecology degree program, which is designed for students who want to go into careers in fields like environmental law, journalism and sustainability. A prime example of UGA’s experimental learning initiative, it provides training in communication as well as a solid grounding in science. The second program is Watershed UGA—a university-wide initiative to foster a culture of sustainability through research, teaching and service.

“It doesn’t matter if we know what the science says about pollution targets, water needs, etc., if we aren’t able to communicate that to the public,” Fowler said. “We have to make people both care about and understand the importance of environmental protection.”