Books are a big deal. The invention of writing is one of the pivotal moments in the history of humanity, and—in terms of cultural significance—the distance from writing itself to the book is literally just the turn of a page. Books existed long before printing presses. As artifacts, they tell stories that range far beyond the mere words printed or written on their pages.

Nora Benedict wants to tell those stories.

An assistant professor of Spanish and digital humanities in the Franklin College of Arts & Sciences Department of Romance Languages, Benedict studies the history of the book—not a particular book nor author, but the book itself, as a medium of literature, communication, art, commerce, politics, religion and all the human activities that express themselves through an object most of us simply take for granted.

“By studying books, we learn a lot about the people who made them,” said Benedict, winner of UGA’s 2023 Michael F. Adams Early Career Scholar Award. “It’s a different way of studying the history of culture, of people, of ideas. Some scholars in book history may think about the physical features of books—for example, what pocket-sized books might tell us about a specific people in a specific time and place, versus those who used giant elephant folios—but you might also look at things like the publishing industry and how books are produced and get into our hands.”

Mapping the world of Borges

Benedict’s focus is on the latter: the business of books. Her first monograph, “Borges and the Literary Marketplace: How Editorial Practices Shaped Cosmopolitan Reading” (Yale University Press, 2021), is a deep dive into Argentine author Jorge Luis Borges and his involvement in the publishing world.

Borges, whose life spanned most of the 20th century until his death in 1986, was an essayist, critic, poet and short story writer whose work greatly influenced world literature. But he was also a fixture in the Buenos Aires publishing industry, co-founding two literary journals as well as working as an editor, translator and literary adviser for various firms.

As an undergraduate and graduate student, Benedict studied English and Latin American literature, Spanish language, as well as art history—all disciplines that might have brought her into contact with Borges. In the end, their connection was made by circumstance and the University of Virginia’s Special Collections Library.

“I received a fellowship to research in UVA’s Special Collections Library during my first summer as a Ph.D. student, and I worked with their Borges collection. My ideas developed from there,” she said. “I started examining the physical features of Borges’ manuscripts and thinking about how he was writing, how he was constructing literature in both a conceptual and physical sense.”

Another one of UVA’s strengths, Benedict said, is work in digital humanities, and this came in handy for her while researching for her dissertation. At the time, one Argentine periodical was only available to her via CD-ROM—a virtually ancient technology by the mid-2010s—but the former head of research and development in the UVA Scholars’ Lab was able to help her extract what she needed from the disc.

“I became really interested in what technology could do for my research more broadly,” she said. “It led me to think about not only the technology of books, printers and presses, but also modern technology as another tool to expand my research.”

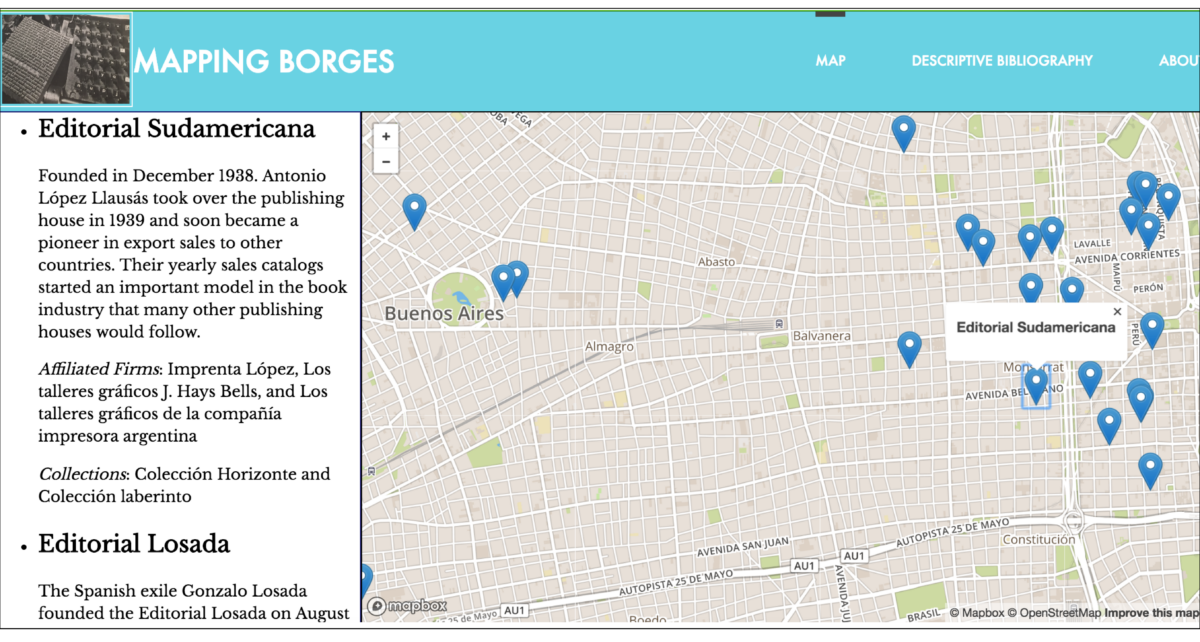

Her new interest turned into a Digital Humanities Fellowship that allowed her to develop a project that first became part of her dissertation, then an online appendix to the physical book she would write. “Mapping Borges in the Argentine Publishing Industry” is a mapping and data visualization project that traces the role of publishers and printers in Borges’ Argentina and provides a digital archive of records of the physical features of books from that moment in history.

The project has two distinct elements: First is an interactive map of the locations of Borges’ publishers, printers, booksellers and places of employment from 1930 to 1951. The second part is a descriptive bibliography, a description of the physical elements of books that Borges wrote, prologued, translated or edited during the 1930s and 1940s.

“In light of the fact that there are virtually no extant publishers’ archives from the Argentine firms I studied for my research,” Benedict said, “I see this digital appendix as a way to give future scholars access to much of the raw data I created throughout the process and, hopefully, provide them with a resource to create projects of their own.”

Technology and the humanities

Benedict wrote all her own code for the “Mapping Borges” project and still maintains the website herself. It was important, she said, to keep the site bare bones, limiting its bandwidth requirements so it remained accessible to people in places with low internet connectivity.

After finishing her Ph.D., she held a postdoctoral fellowship at Princeton University and began a second digital project that eventually led to an idea for the book she’s currently writing on global publishing. This time focusing on the publishing enterprise of Argentine writer Victoria Ocampo, Benedict built a relational database and generated a series of network graphs centering on Ocampo’s professional contacts and connections, which she augmented with an interactive map that gives users a better sense of this Argentine’s global reach and impact.

When she came to Athens in 2019, Benedict was happy to discover UGA had its own digital humanities culture, concentrated in the Willson Center for Humanities & Arts DIGI initiative and the DigiLab on the third floor of the Main Library, where students and researchers can go for help with things like text mining and linguistic analysis of large datasets. She’s well acquainted with the added dimensions technology can bring to humanities research—as long as the researcher doesn’t lose sight of the humanity underneath the technology.

“Technology is a tool—not an end in itself,” Benedict said. “I don’t think someone who teaches French poetry needs to incorporate ChatGPT into their classroom for fear of obsolescence, but at the same time people need to be aware of these tools and how they can help address certain research questions.”

Indeed, Benedict sees technology as another method researchers can use to push their questions further, to take that additional step or two of inquiry, and that innate curiosity is something that is inherent in humanities research itself. It’s something Benedict heard more than once during the events of UGA’s first Humanities Festival, held this spring.

“It was really important to see individuals from classics and history, but also disciplines like neuroscience and law, talk about their winding paths,” said Benedict, who served on the Humanities Council that planned the festival. “During one event, someone talked about how essential humanistic inquiry is for any type of research, but especially those fields outside of the humanities.

“In the humanities, there is always this continual return to the question of ‘why?’ Even though we have proved our claim or made a sound argument, the conclusions are still open for debate. It’s a continual learning process, not only about ourselves, but about humanity at large.”