Her team’s expertise is also going to play a key role in a new $23 million joint project, with Virginia Tech and other universities, funded by the National Science Foundation. The goal is to build a facility specialized in creating glycopolymers (chains of carbohydrates) with specific applications, such as a new plastic or drug. Azadi’s team will make sure the polymers have the exact structure—and, therefore, function—that they need.

“The polymers we have in nature have complicated structures we cannot change,” said Azadi. “We want to be able to create the exact structures that we want. So we’re synthesizing on demand, but it’s much harder with glycans because of their complexity, and it’s difficult to position each unit exactly where you want them.”

Azadi, together with CCRC Director Alan Darvill, also heads the Department of Energy Center for Plant and Microbial Complex Carbohydrates. The center is the longest-funded multi-PI center at the CCRC, with research focused on the structure, function and biosynthesis of complex plant and microbial cell wall carbohydrates that have many potential applications for commercial use.

To share the knowledge built working at the cutting edge of glycoscience, Azadi coordinates specialized training courses in carbohydrate analysis annually for about 50 people. COVID-19 drove the course online this year, and in August she and CCRC faculty trained more than 300 scientists from all over the world.

“COVID has presented us with so many challenges, but also some opportunities,” said Azadi. “We were able through the training courses to interact with a large number of scientists who would never have had the chance to participate in person, really wonderful scientists who just don’t have the capability to travel.”

In September, Azadi was also asked by the National Institutes of Health and U.S. Food & Drug Administration to organize a training course in new glycoscience techniques for 40 of their scientists. She enjoys sharing her excitement over the doors that carbohydrate science could open.

“The first six months of my Ph.D. really opened my eyes to this hidden gem [of glycoscience], like a black box that needed to be opened,” said Azadi, who earned a Ph.D. in biochemistry in 1991 at Imperial College London. “The field was really young at the time and very few people were working in this area, especially structural aspects of it.”

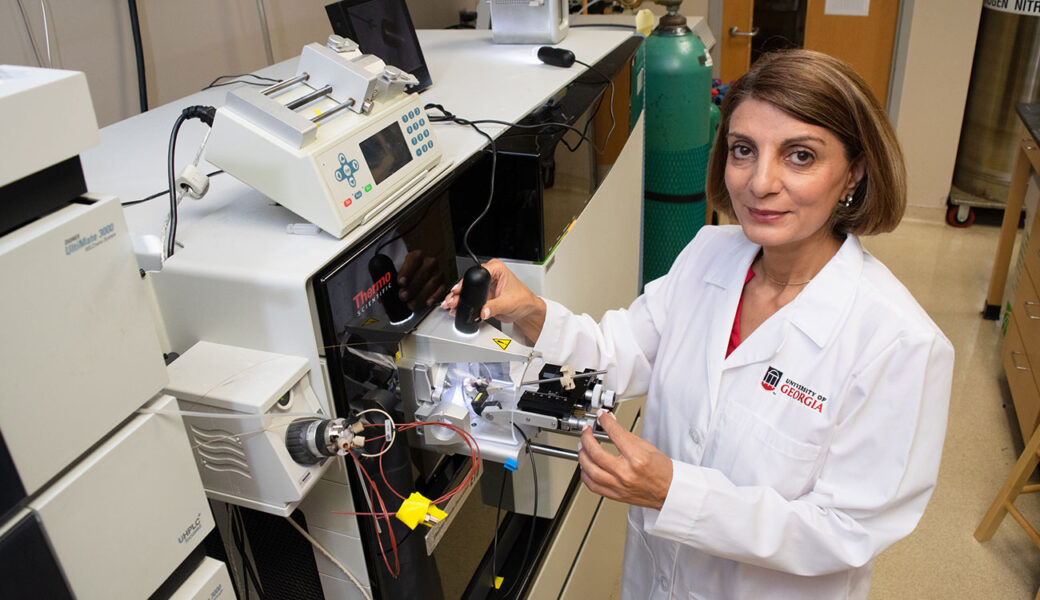

After her Ph.D., she continued to gain key expertise in mass spectrometry, working for a company called M-Scan in the U.K. and providing analytical services to the pharmaceutical industry, before joining CCRC in 1994. Since 2001 she has been technical director of AST.

“I hope students coming into this field will still feel the excitement that I felt 30 years ago,” Azadi said. “There’s just still so much potential.”