In a nondescript brick building on Whitehall Road, miles away from the bustle of UGA’s campus, thousands of years of history wait quietly to give up their secrets.

The UGA Archaeology Lab’s newest home may have only opened its doors in 2018, but the collections inside tell a story that spans the millennia of human habitation in the land now called Georgia. There are sherds of pottery fired by indigenous Americans while the Han dynasty ruled in China, human effigies molded as Charlemagne was being crowned, glass vials of “pharmaceuticals” sold during Reconstruction—all markers of the cultures that have called this land home.

During the pandemic year, archaeological fieldwork ground virtually to a halt. But inside the Archaeology Lab, discovery continued as faculty, staff and students turned inward to the collections already in hand, using 21st-century technologies to peer more deeply into ages past.

“Archaeology is one of those really interesting disciplines in that there’s this inherent curiosity that we have about where we come from,” said Victor Thompson, professor of anthropology in the Franklin College of Arts and Sciences and director of the Archaeology Lab since 2019. “Regardless of whether you saw Raiders of the Lost Ark when you were a kid, you’re going to have an interest in it because it gets back to that fundamental question: Who are we?”

Storehouse for the past

Indeed, visitors to the Archaeology Lab’s storage area will immediately recall the famous closing image of Raiders—which celebrates its 40th anniversary this summer—as the famed Ark of the Covenant is nailed into a wooden crate and wheeled into a cavernous room of identical crates stacked high.

That’s where the similarities between Hollywood and real-world archaeology end. Not only do Indiana Jones’ treasure-hunting adventures bear little resemblance to the painstaking, culturally respectful work of modern professionals, but the Ark’s implied fate—to be tucked away in some dark warehouse, never to be seen again—is exactly the opposite of how UGA views and manages its collections.

UGA is one of three main repositories for archaeological artifacts that fall under the purview of the Georgia Department of Natural Resources, and the lab also curates for the National Park Service, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the U.S. Forest Service and the U.S. Navy. Most artifacts are from Georgia, but not all; the lab houses for the Navy a large collection of objects collected in Puerto Rico.

Dozens of requests come in to the Archaeology Lab each year to study its 50 million artifacts and paper and digital archives. The collections are housed in 15,000 square feet of curation space that is already nearing capacity, Thompson said, despite $120,000 in high-density, moveable shelving that was recently installed (thankfully, more is on the way in 2022).

“At DNR, we own or manage about 2 million acres in the state, so we’re the stewards of very significant cultural and archaeological resources. Any time an archaeological investigation is done and artifacts are recovered, per federal law, we are required to keep those artifacts in perpetuity,” said Rachel Black, Georgia’s state archaeologist at DNR. “We curate quite a bit of our DNR collections at UGA and continue to curate new collections with them moving forward.”

Those collections comprise only part of the lab’s research resources; UGA also serves as the official custodian for the Georgia Archaeological Site File, a database of information about historic properties and archaeological sites around the state. Whenever a new capital project gets underway, developers typically hire a private archaeology firm to do a site assessment, and consulting the Site File is first thing they do.

“I was on it yesterday, and I’ll probably get on it today,” said Scot Keith, senior archaeologist with the firm Southern Research, who earned his bachelor’s in anthropology from UGA in 1992 and worked on the Site File himself as a student. “We used to physically go to Athens and look through the files. Now it’s all online, but that’s still the first step in archaeology.”

Making the most of a pandemic

Activity inside the Archaeology Lab also paused once COVID hit, but it recovered much more quickly than fieldwork. Once UGA commenced its phased reopening for on-site research last summer, the lab staff quickly put together protocols that allowed UGA faculty and students to return. They might not have been able to dig, but there was still more than enough to do.

“It turned out to be an easier transition than I thought,” said Amanda Thompson, the lab’s operations director. “We were able to switch to doing a lot of tasks digitally and remotely pretty easily. And as soon as we had our protocols in place and the lab set up for social distancing, things picked right back up, and we got caught up really quickly.”

For example, the pandemic put on hold the lab’s significant outreach activities—in 2019 it hosted nearly 140 tours and participated in numerous outreach events, both at the lab and elsewhere around the state—but the extra time provided opportunity.

Once they were allowed back in, students resumed certain research and curation tasks that pulled double duty for public relations and outreach. Invariably, lab visitors (especially children) want to touch artifacts and satisfy that human need for physical connection. Rather than allow visitors to actually handle 1,000-year-old pottery sherds (an archaeological term for ceramic fragments, more specific than “shards”), lab staff scan artifacts and create replicas using a 3D printer, then hand these faux fragments off to student artists for painting. The final product—at least to an amateur eye—is indistinguishable from the real thing.

Researchers also created or reassessed digital inventories of pieces both old and new. Some of the longer-held collections were still in their original paper bags that were in danger of deteriorating, and these were moved to plastic bags for better preservation. More than 30 newly acquired collections were processed for curation.

“We have dozens of master’s and Ph.D. theses in these collections just waiting to happen,” said Jennifer Birch, associate professor and undergraduate coordinator in anthropology. “This is especially because the pace of archaeological science has been accelerating over the last 20 years. The technology we have now to extract new information from these old collections was unimaginable when these sites were actually excavated.”

Postdoctoral researcher Carey Garland spent much of the pandemic microsampling oyster and clam shells recovered from coastal sites in Georgia, South Carolina and Florida in order to perform stable oxygen isotope analysis on them. Many of the shells came from the Tampa Bay region, which about 1,000 years ago was home to the rising Tocobaga chiefdom, a group that constructed large mounds out of earth and oyster shells and would encounter several Spanish expeditions in the 16th century.

“We have a fantastic opportunity to expand the repertoire of designs that we know about through this work,” Smith said. “You’ll find a unique design from a site, and you might find that same design at another location—you can tell from a crack in the paddle or a particularly unique flaw in the design. It’s almost a fingerprint. To be able to track that paddle in space as the person who held it moved around, there’s almost nothing like it in our field.”

Indeed, what can sometimes get lost in anthropological and archaeological research, which often tries to build understanding of broader cultures and trends, is the fact that all of these artifacts were made by individuals. And that leads directly to what has become one of the Archaeology Lab’s most vital projects.

“One of the most important things we do—maybe the most important thing we do—is our work under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act.”

– Victor Thompson, director of the Archaeology Lab

Photo by Nancy Evelyn

Respecting history

Locked in a separate enclosure behind all the rows of shelving are the Archaeology Lab’s most irreplaceable collections, those considered invaluable by the region’s indigenous cultures. Among these special collections are Native American ancestral remains, as well as funerary and other revered objects, that were considered sacred by the cultures that left them. And they are just as sacred now to those people’s descendants.

“One of the most important things we do—maybe the most important thing we do—is our work under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act,” said Victor Thompson. “We’ve shifted our operations to go beyond statutory requirements and proactively involve tribal communities in everything we do.”

Passed in 1990, NAGPRA requires institutions receiving federal funds to return ancestors and certain Native American cultural items to descendants and affiliated tribal nations. Since Thompson became Archaeology Lab director, he has significantly stepped up its NAGPRA-related activity. The inventory work that occupied much of the pandemic provided him and his team with more detailed information about UGA’s collections (as well as a lot of time spent not in the field) that helped invigorate the lab’s communications with the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, the Seminole Tribe of Florida, the Coushatta Tribe of Louisiana and other tribes.

NAGPRA doesn’t necessarily require that every item of significance be physically returned to a tribe. Often the goal is simply to give objects the respect they deserve, which can involve special curation techniques or keeping certain objects out of public displays or exhibitions. One vivid example is the special collections area itself—when the Archaeology Lab first opened, its holdings were visible through its steel mesh walls. Now the entire enclosure is shrouded in black, out of sight from casual passersby, and the lab hopes to create an entirely separate, secure, climate-controlled NAGPRA wing from its current storage area in the back of the facility.

“UGA upholds a high standard for transparency, tribal engagement and communication that I would love for all the other institutions to be held to—they’ve really made great strides just in the last few years to improve and increase tribal engagement,” said Miranda Panther, NAGPRA officer for the Eastern Band of Cherokee’s Tribal Historic Preservation Office.

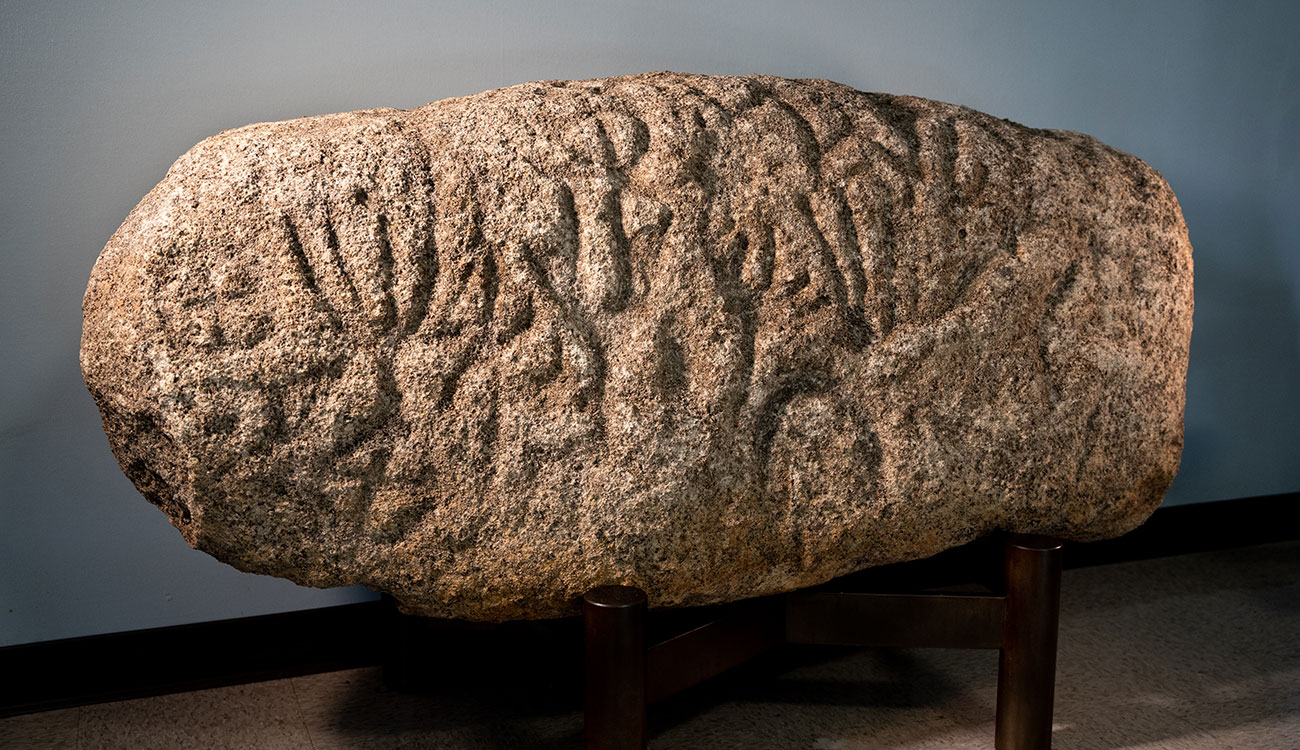

Another example is the current effort to find a permanent home for two large petroglyphs that are carved on boulders and have occupied various locations on campus since they were gifted to UGA decades ago. It’s unknown exactly how old the carvings are or which culture created them, but Thompson is raising funds to give the petroglyphs a proper home at the Archaeology Lab. The smaller boulder has already been moved to the lab’s lobby, and UGA is working with Muscogee (Creek) artist Dan Brook to design and build a culturally appropriate shelter to house the larger stone.

“What I really like about this job is helping people make a connection to the past, but also extending that connection to the people who are still living today, the people who still have ancestral connections to Georgia,” said Amanda Thompson. “The relationships we’ve made with our tribal partners have been so rewarding. They’ve enriched what we do and made what we do better.”

Both Thompsons and their colleagues have secured funding—from the National Park Service, for example—to support their NAGPRA work. This spring they drafted the lab’s first official policy and standards document that will guide how the Archaeology Lab incorporates NAGPRA into all of its activities. It’s a win-win situation for all involved, they say, because not only is abiding by NAGPRA federal law (and simply the right thing to do), but it also benefits the research itself by providing a more complete understanding of the cultural context in which archaeological artifacts are created.

“Archaeologists haven’t always consulted with these groups and have treated our work more as a hard science, as opposed to something that touches the histories of people who are still alive today,” Birch said. “These groups are very concerned with writing their own histories—they know this stuff.”

“Tribes aren’t scared of science—they’re subject matter experts on a lot of things archaeologists are seeking answers to,” Panther said. “It can be a very mutually beneficial relationship. UGA has a great facility for meeting the standards set forth by NAGPRA.

“I feel very secure knowing these collections are in safe hands there.”