While many people know that the microbes in our guts are an important part of our health, many are unaware that microbes are just as important to our crops.

Different microbes can help plants acquire nutrients, fend off pests and disease, and produce higher yields, but we know very little about how these partnerships work. University of Georgia researchers are working to understand these partnerships so that they can be used to breed better, more sustainable crops.

A team of researchers at the UGA College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences has received a $1.35 million grant from the National Science Foundation to better understand how plants interact with their microbiomes.

“Just like people, plants host trillions of microbes that live on, around and inside them,” said principal investigator Jason Wallace, a CAES professor of crop and soil sciences. “Some of these cause disease but many are beneficial, helping the plant thrive in harsh conditions, but we don’t know how this interaction works. Learning how a plant’s microbes make it more resilient could be an important key to developing more sustainable and stress-tolerant crops in the future.”

Wallace’s team is focusing on a grass called tall fescue, which has been grown for animal feed for more than 70 years and covers 40 million acres across the U.S.

While breeding more water-efficient fescue has been a goal of plant breeders for decades, UGA geneticists are taking a new approach. They are investigating how the grass interacts with symbiotic fungi, which has been found to fortify it against heat and drought stress.

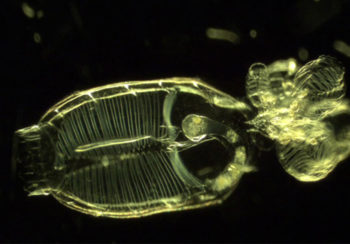

Some types of tall fescue have a fungus, Epichloe coenophiala, living inside them, which helps the plant survive drought, heat and disease. It also helps the grass fend off insects and predators.

Ironically, this partnership was discovered because the fungus usually produces toxic chemicals, ergot alkaloids, that make cattle sick. UGA was instrumental in breeding the first commercial varieties with toxin-free strains in the 1990s.

Wallace’s team will be working with fescue that contains the fungus to understand how such a beneficial partnership works, including how the plant and fungus communicate with each other and how their interaction leads to higher stress tolerance in the plant.

The hope is that understanding this system will show how similarly strong, beneficial partnerships can be made in other crops to boost agricultural production and sustainability.

Wallace is partnering with Carolyn Young, an associate professor at the Noble Research Institute in Ardmore, Oklahoma, to carry out this research.

To complete this work, Wallace, Young and their research teams will analyze thousands of fescue plants to find how the plant influences fungal growth and toxin production. They will also investigate how the plant forms relationships with new varieties of fungus, such as ones that do not produce toxins, and how the fungus helps the plant survive under heat stress that would normally kill it.

In addition to the work with fescue, Wallace and Young will assist middle and high school teachers in developing hands-on teaching projects related to these topics that they can implement in their own classrooms. This will give students a better understanding of plant-microbe partnerships and the ways that microbes impact the larger ecosystem.

The grant period will run from 2019 through 2022.