Dr. McCully, you have more than 20 students working in your lab, and the majority of them are undergraduates. What are the benefits of having undergrads in the lab?

McCully: We’ve had quite a few undergraduate projects that have advanced the knowledge of our lab. I definitely use their efforts to help learn things I didn’t know before. I also think having a lot of creative, hard-working, enthusiastic kids in a laboratory changes the atmosphere. Our laboratory has a very different vibe or atmosphere than many science labs. When you study human beings, having a lab that’s very positive is great. For example, our lab has coffee all the time and chocolate most of the time.

We had a research grant to study people with spinal cord injury, and I was meeting with the program officer at the National Institutes of Health. She asked, “How do you make sure that the subjects stay in the study and don’t quit? Shouldn’t you do something like ‘The Biggest Loser?’” I told her that I don’t have to. Our study subjects meet my undergrads and then they’re so excited to come in, they never drop out. One hundred percent of the people with spinal cord injury stayed with the program because they like the atmosphere of the lab. Having undergraduate students in my lab makes it a friendlier, fun place.

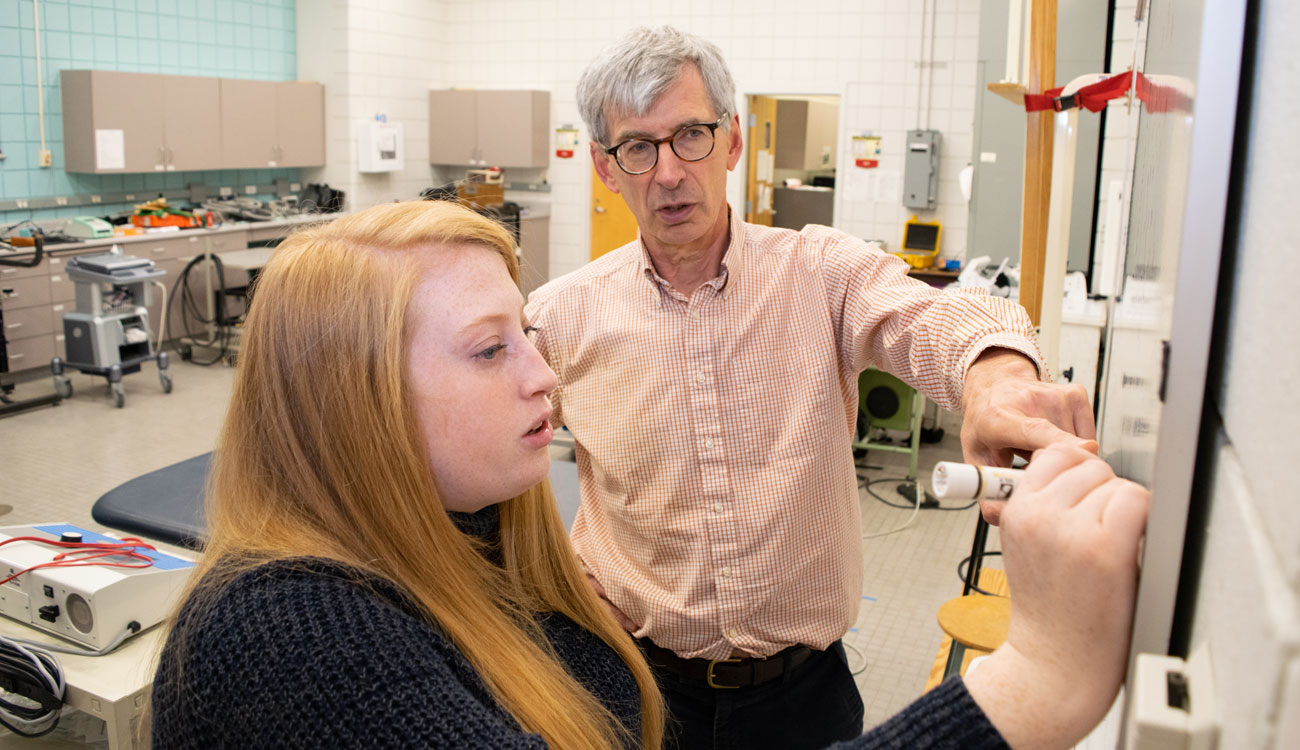

Emily, what kinds of projects have you worked on?

Jones: For my first project, we used an accelerometer that sits on top of the skin and measures the twitch contraction. As the muscle fatigues, the twitch gets smaller and smaller. We were trying to determine if the amount of subcutaneous adipose tissue would affect the way the accelerometer could read the contractions. We wanted to determine if we could get valid results with someone who was obese versus someone of normal weight.

McCully: All of our original papers on this method used a nine-minute long program, but then we decided that we needed to make it shorter. Emily actually showed that you get the same results with five minutes as you do with nine, so why not go shorter?

Jones: We do a lot with clinical populations, and one of our main goals is to make them feel as comfortable as possible. Electrical stimulation isn’t painful, but a lot of people find it uncomfortable and kind of an annoying sensation. We were trying to see if we could take our protocol and adjust it to where it was five minutes at a different hertz level versus a nine-minute stimulation to see if we could get significant results, and we did.

Emily, what have you learned from working in Dr. McCully’s lab, and how has it affected your plans for the future?

Emily, what have you learned from working in Dr. McCully’s lab, and how has it affected your plans for the future?

Jones: I started at the lab in my sophomore year, and I absolutely felt like I knew nothing. But the older kids in the lab took me under their wing and showed me how to do analysis, how to do the tests, how to interact with people and how to be professional with participants. Dr. McCully can attest to this—I was the least confident person in my knowledge when I started in the lab, but working with the students gave me the confidence to believe that I could do my own project one day. Now I’m in the position where I’m teaching kids who are like, “I have no idea what I’m doing.” It’s been a complete 180.

I’m going to graduate in May and begin a nurse practitioner program at Emory University. I want to do orthopedics, which has come from my love of exercise science. The structure of the body amazes me.

Dr. McCully, how does working in research benefit the students in your lab?

McCully: Most of the students in my lab don’t want to do research as a career, but I think they still find it valuable to be in a research laboratory. We have a lot of people like Emily that want to be nurses, physicians, occupational therapists, dentists. I usually tell them that the report that you would give for your experiment is the same report you’d give for a patient in a hospital bed. The same steps, all the way through. Why is the person here? What tests did we order? What were the results of the tests, and what are the actions that you’d follow based on the tests? That’s what you do in science, and that’s exactly what you do with a patient.

Being in a lab is an active learning environment, and you have to take advantage of it. And if you do that, the way Emily did, then you grow and get better, and it’s fantastic. My thing is to get people to try, to take chances. I think it provides a depth to your education that you wouldn’t have had otherwise. [turning to Jones] I think your whole undergraduate experience would have been different had you not been in a research laboratory.

Jones: Yes. The way Dr. McCully structures the lab makes it a very active learning environment. I think that’s how you learn best in the research field—being told but then actually being allowed and given the responsibility to do things.