Dr. Yaguang Xi began his career in the 1990s as a practicing surgeon. But after helping perform a procedure that, while technically successful, still couldn’t save his 17-year-old patient from a recurrence of deadly gastric cancer, he began thinking more deeply about the disease’s root causes.

“I thought we had saved her, but we couldn’t,” he said. “I was shocked. I was doing the surgical part, doing my best, but I had no way to save this girl’s life.”

Cancer is the second leading cause of death in the United States, surpassed only by heart disease. Last year, an estimated 1.9 million people nationwide received a cancer diagnosis—and that number doesn’t include basal skin cancers or carcinomas in situ.

For patients and researchers alike, cancer is a formidable opponent.

It takes a special combination of doggedness and heart to become a cancer researcher. At The University of Georgia Cancer Center, founded in 2004, some of UGA’s finest scientists have embraced the challenge.

“We have a great diversity of members, close to 40 faculty from 20 different departments,” said center director Eileen Kennedy, a Georgia Athletic Association Professor in the College of Pharmacy. “Our researchers bring complementary expertise. We’re looking at diagnostics, prevention, and therapeutics, targeting discovery and translation in these three areas for the patient setting.”

Early diagnosis and treatment provide the best chance at a positive outcome, Kennedy said. And even prior to diagnosis, these researchers are interested in ways to lower cancer risks—through diet, environmental changes, and knowing family history, for example.

“We want to do something that is impactful,” Kennedy said, “For us, that means how can people survive? Strategies, treatments, understanding the mechanisms of cancer. What is going haywire in the cells, and how can we look at reprogramming that to regulate that cancer signaling?”

The center’s tripartite mission aims to develop new and better diagnostics for cancer, novel drug treatments, and meaningful preventive measures. As they develop these tools and therapies, UGA Cancer Center researchers are helping transform the meaning of a cancer diagnosis for future generations.

Research that saves lives

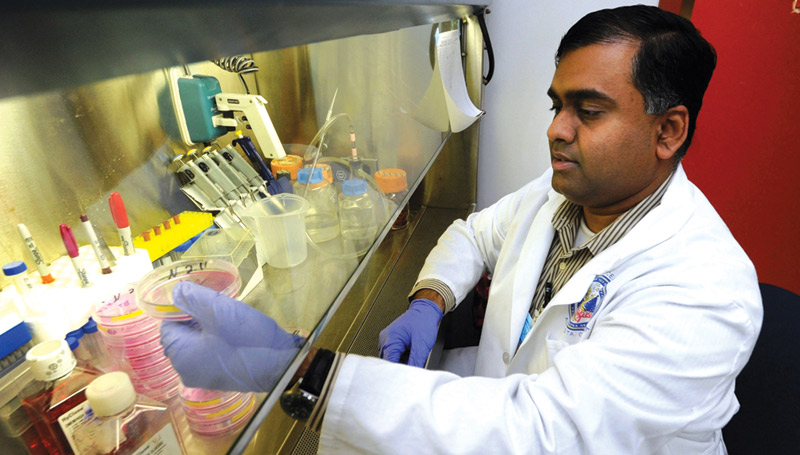

For Xi, losing that 17-year-old patient led to a change in his professional trajectory. He went on to earn a doctorate in cancer biology from Peking University in China and launched a successful career in cancer oncology research. Now in his first year as professor and chair of the Department of Pharmaceutical & Biomedical Sciences at the UGA College of Pharmacy, Xi recognizes the deep connections between his laboratory research and the welfare of cancer patients.

“I have a clinical background,” he said. “I want to address clinical challenges. So, when I’m in the lab trying to determine how a given molecule functions, that’s my path to a larger goal: How can these discoveries lead to a treatment that helps the patient? I want to help save as many lives as possible.”

Xi’s translational research, which has garnered multiple National Cancer Institute (NCI) R01 grants, currently aims to develop treatments that halt tumor metastasis in colorectal cancer. Studies have shown that around 85% of patients with colorectal cancer do not respond to the latest immune checkpoint inhibitor therapies. Xi’s lab, however, has repurposed a common non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) to create a new combination therapy that improves these patients’ responses.

“This new approach can increase patient responsiveness and enhance the efficacy of the immune checkpoint inhibitors,” Xi said. “And because we’re repurposing an already-established drug, we can more easily move to Phase 2 trials.”

With support from the UGA Cancer Center, Xi is forming strategic partnerships across Georgia, seeking collaborators to launch a clinical trial. While the health care and scientific interest is strong, the potential revenue from a repurposed NSAID isn’t enough to appeal to most pharmaceutical funders. Xi sees that as a reason to keep pushing.

“This is affordable cancer care,” he said. “This treatment could help people in low-income populations. But we need funders willing to step in and help us do the study.”

In addition to related research exploring a new treatment for triple negative breast cancer, Xi is spearheading initiatives to establish an artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted drug discovery research program at UGA—and a graduate track for cancer research in his department. It all comes down, he said, to collaboration.

“We’re forging interdisciplinary programs to enhance our research and educational mission,” he said. “Our inaugural project will focus on cancer drug development utilizing AI.”

Cancer treatment for a new age

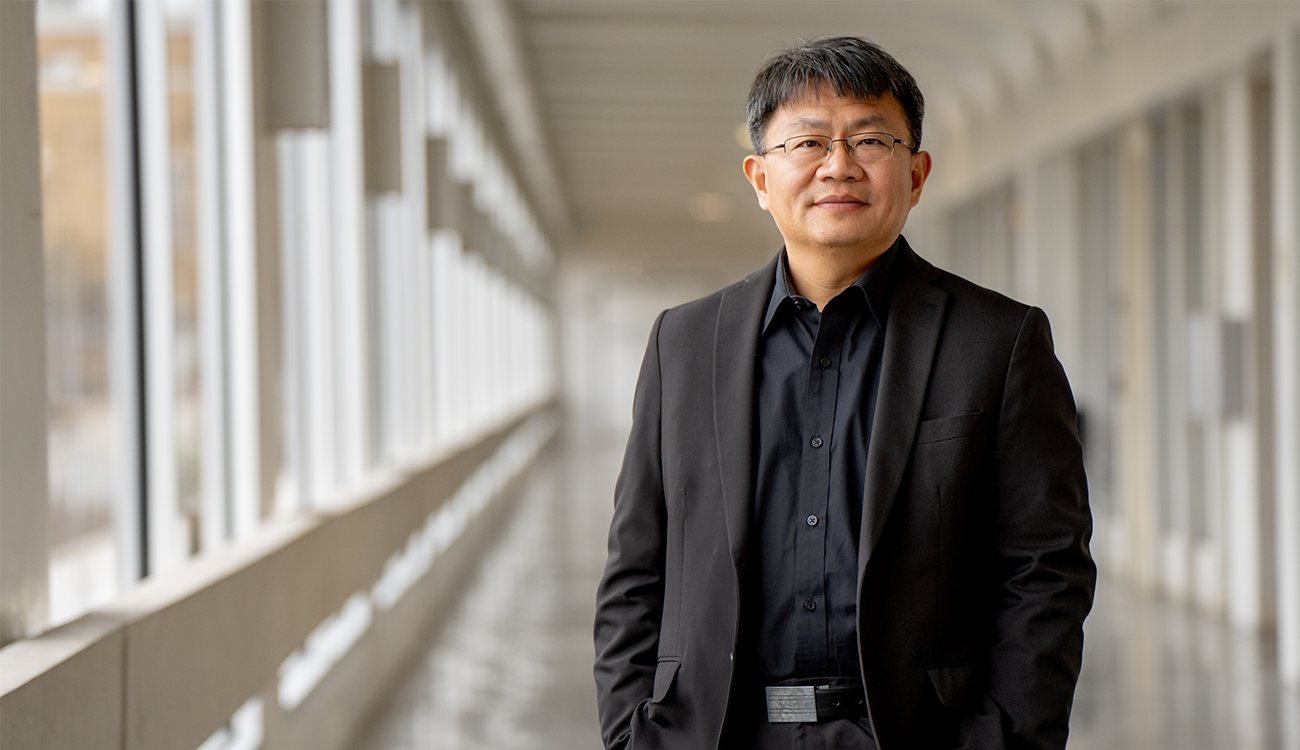

Natarajan Kannan trained as a physicist because he likes tackling problems that most people would consider unsolvable.

“I love studying complex systems,” he said. “I was getting to the end of my undergraduate degree, and my professor said that the next major challenge would be to study complex evolutionary processes, such as cancer, using quantitative techniques. That opened the door.”

Today, as a Georgia Cancer Coalition Distinguished Scholar and a professor of biochemistry and molecular biology at UGA’s Franklin College of Arts and Sciences and Institute of Bioinformatics, Kannan investigates understudied protein kinases, part of a class of enzymes causing mutational changes that can lead to cancer.

“Protein kinases function as ‘on-off’ molecular switches,” Kannan said. “They regulate cellular signaling pathways that underlie cancer initiation and progression. But we don’t know enough about them, since only a few of these kinases have been well studied.”

Kannan’s lab participates in the National Institute of Health’s Illuminating the Druggable Genome Consortium(IDG), a nationwide push to improve scientific understanding of understudied protein families through the development of new tools and an information repository.

“We have large amounts of data already available on the well-studied kinases,” Kannan said. “Can we mine this data to shed light on the understudied ones? They’re all related; they’re in the same family tree.”

Working alongside faculty at the UGA School of Computing, Kannan developed the Protein Kinase Ontology, a mineable knowledge map for integrating diverse forms of data on protein kinases and cancer.

“These knowledge maps tell a computer how different forms of data are related to each other,” he said. “We do this in a way that humans can understand and computers can mine, so cancer researchers and clinicians can use the knowledge map for drug discovery efforts.”

The team’s ultimate goal is to implement these tools in a clinical setting—one where the physician can ask questions in a manner analogous to ChatGPT, Kannan said, and the answers he or she receives can guide further treatment options. The end result could be a personalized treatment plan that takes both individual and aggregate patient data into account.

“This is accelerating personalized cancer treatment for the AI age,” he said.

Already, his team has begun testing how certain molecular mutations are implicated in specific human cancers. Kannan is also collaborating with other UGA Cancer Center faculty to develop novel chemical probes for misregulated kinases. In the prevention arena, he recently published a paper investigating the role of understudied metabolic kinases in human cancers—proteins that turn on or off based specifically on dietary patterns. Dietary patterns could be key to helping prevent many cancers from forming in the first place.

“There’s a strong need to map the relationships that connect diet, metabolism, and cancer,” Kannan said. “These new methods of data mining are important to cancer prevention.”

“We want to do something that is impactful. For us, that means how can people survive? Strategies, treatments, understanding the mechanisms of cancer. What is going haywire in the cells, and how can we look at reprogramming that to regulate that cancer signaling?”

– Eileen Kennedy, UGA Cancer Center director and Georgia Athletic Association Professor in the College of Pharmacy

Treating our pets

Corey Saba has a different patient roster than you’d expect from an oncologist. Her patients can’t tell her how they’re feeling—at least not in words.

A professor of oncology in the Department of Small Animal Medicine & Surgery at the UGA College of Veterinary Medicine, Saba conducts clinical trials of the latest cancer therapeutics for dogs, cats, and horses. Her investigations hold promise both for animals who receive a cancer diagnosis—and potentially for humans suffering from related cancers.

“Dog cancers are very similar to human cancers,” she said. “So, the purpose of some of these trials is to investigate novel cancer therapies that could end up in human clinical trials.”

To that end, Saba and her collaborators have conducted extensive clinical trials of rabacfosadine (Tanovea), a chemotherapy treatment for canine lymphoma. These studies, which involved more than 600 dogs seen over a 15-year period, led to the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) decision to grant conditional approval of the treatment in 2016 and full approval in 2021. Tanovea is the first new animal drug to receive full FDA approval under the Minor Use and Minor Species program.

This achievement is a potential game-changer for dogs with lymphoma. The development of drug resistance is a major problem in the treatment of canine lymphoma, often occurring within a year of starting treatment. Tanovea’s mechanism of action differs from other drugs used to treat the disease, and its addition to the treatment arsenal provides hope for longer remission durations.

In related efforts, her team recently replicated a trial that helped confirm the viability of a less time-intensive treatment protocol for administering Tanovea—a finding sure to be useful for busy pet parents.

Saba’s on-campus partners include colleagues with the SMART Pharmacology Lab in the College of Veterinary Medicine. Going forward, the team will be investigating new immunotherapy drugs for pets and companion animals.

“Immunotherapy has played a role in the treatment of human cancers for years,” she said. “With one of the first canine-specific immunotherapies just released last year, the field is wide open for discovery.”

While the work is intense, Saba stays motivated by her concern for the animals that don’t have good treatment options yet.

“The diagnosis of cancer is always devastating, even in our four-legged family members,” she said. “I’m proud that I can help guide pet owners through the process.

“I went through veterinary school with an interest in pathology and cancer biology. My father died of colon cancer during my internship year. That experience helped me further appreciate the need for cancer research, novel treatments, and maybe one day a cure.”