Though tuberculosis (TB) is an old disease, with cases dating back 5,000 years, it remains a major global health threat. Accurately detecting latent TB infections, when the infection is still dormant and not actively making a person sick, is key to public health efforts to eliminate the disease.

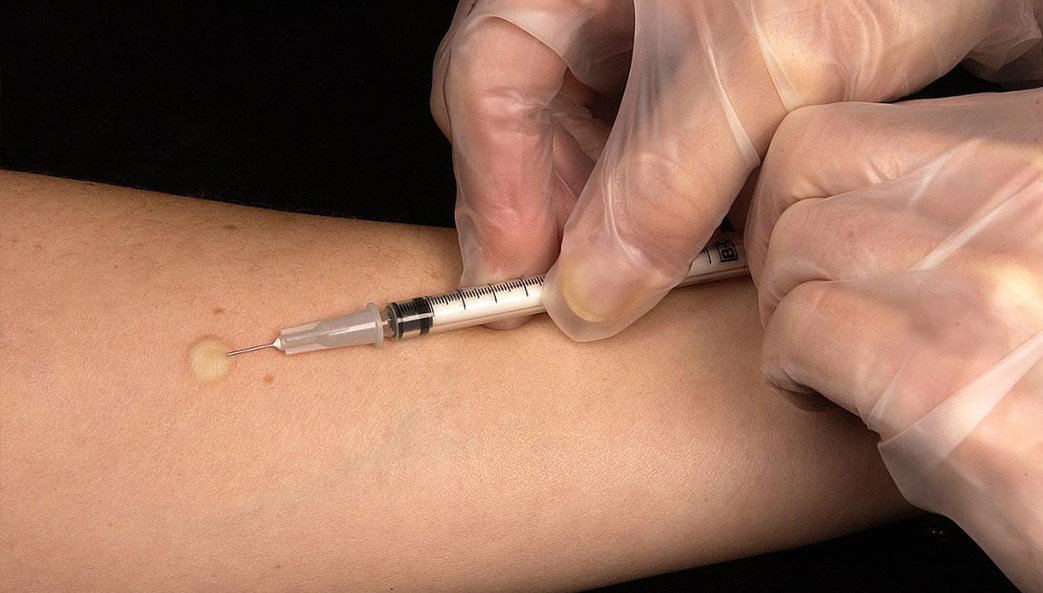

New research from the University of Georgia is the first population-level study to examine whether the primary diagnostic tool for latent TB, a tuberculin skin test, could misidentify individuals as new cases of latent TB in areas where the disease burden is very high.

The proper identification of new cases using the tuberculin skin test has implications for who is treated, says Juliet Sekandi, an assistant professor in the Global Health Institute at UGA’s College of Public Health and lead author on the study.

Sekandi and colleague Chris Whalen were leading a research team gathering survey data in Kampala, Uganda, when they noticed an unusually high rate of reported latent TB, over 50 percent of the population.

“That’s what triggered this study,” Sekandi said. Tuberculin skin tests can be susceptible to “boosting,” she explained, which can occur when the test triggers an immune response from past exposure to TB bacteria, rather than recent exposure. That can lead to a false positive.

“We don’t want to falsely diagnose latent TB because, by policy, it is supposed to be treated,” said Sekandi. “You treat for six to nine months, so if you’re going to give somebody treatment for nothing when it’s just a boosted reaction, that’s not good.”

In addition to protecting the patient from unnecessary side effects, it can be costly to treat people who don’t need it. It’s estimated that one-third of the world’s population have latent TB infections, but treatment resources are limited. Public health programs can’t afford to treat a large number of misidentified patients.

Researchers recruited volunteers in Kampala, who received an initial skin test. If the test came back negative, the participants were asked to return in two weeks for a second test. Of the 99 participants, only two showed a boosted response, suggesting that their immune systems were triggered by the tuberculin in the first skin test rather than actual TB exposure.

These findings, says Sekandi, are important to public health prevention programs.

“We can be confident we aren’t doing too much harm,” she said. “The takeaway point here is that in high burden settings like Uganda, most of the people that test positive with a skin test are actual cases of latent TB, not just false positives.”

The study “Low Prevalence of Tuberculin Skin Test Boosting among Community Residents in Uganda” was published in the American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. It is available online at https://www.ajtmh.org/content/journals/10.4269/ajtmh.17-0591.

Co-authors include Allan Nkwata, Leo Martinez, Robert Kakaire, Jane Mutanga and Christopher Whalen, with UGA’s College of Public Health; Sarah Zalwango with Makerere University in Kampala, Uganda, and the Department of Health Services; and Noah Kiwanuka with Makerere University.