Research teams at the University of Georgia have successfully discovered a single-dose vaccine that provides complete protection against the Crimean-Congo Hemorraghic Fever, or CCHF, virus in mice, a disease that poses a public health risk and has the potential to cause a major epidemic. Results of the study have been published in Emerging Microbes and Infections.

The study was led by associate professor Scott Pegan at UGA’s College of Pharmacy department of pharmaceutical and biomedical sciences in collaboration with the Centers for Disease Control, led by Éric Bergeron.

Since December 2015, the World Health Organization has maintained a list of Blueprint priority diseases in an effort to accelerate the research and development of urgently needed vaccines and drugs to treat them. This list includes diseases that have the potential to cause major epidemics and no effective treatment or vaccine exists to combat them.

In February 2018, WHO reviewed its Blueprint for the prevention of epidemics and placed Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever at the top of the priorities list. This tickborne viral disease is found throughout Africa, the Balkans, the Middle East and Asia and has the potential to emerge in Western Europe as evidenced by two recent cases in Spain.

First described in Crimea in 1947 and later in the Congo in 1956, CCHF has a high fatality rate: Between 10% and 40% of cases end in death. In some regions, the fatality rate is as high as 80%.

CCHF is acquired through bites from infected ticks of the genus Hyalomma and is also spread by contact with infected animals, such as goats and sheep, or handling infected animal tissue during slaughter. This virus can be spread from human to human in hospitals, placing medical workers at risk. Travelers to regions where infected ticks are found may also contract CCHF.

Often occurring in remote regions, CCHF is difficult to prevent. There is no therapeutic treatment for this disease. Antiviral drugs, such as ribavirin, have not proven effective as a method to treat CCHF.

Previously developed CCHF vaccine approaches have required multiple dosing, which is difficult to provide during a severe outbreak. Up until now, there has been no effective single-dose vaccine to prevent CCHF.

Not only is CCHF a threat to world health, it also poses a threat to national defense. The CCHF virus can be weaponized, and U.S. military forces are exposed to this risk in areas of strategic importance, such as Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria. Consequently, the CCHF virus is included in Bioterrorism Category A by the Centers for Disease Control, along with Ebola and the Marburg virus, among other potential bioterrorism agents.

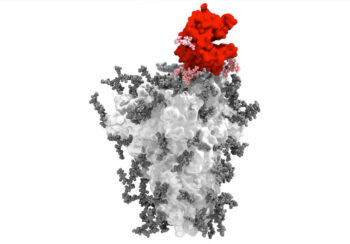

The good news is that when a state-of-the-art CCHF mice model received the new replicon particle, single-dose vaccine, they were completely protected against the CCHF virus. The vaccine not only provides complete protection with a single dose but can be handled in the lab without the biosafety risks of using live virus. Although it closely mimics the structure of the CCHF virus, the replicon particle has been genetically altered to limit its replication to a single cycle so that it cannot proliferate and spread.

Safe and effective in mice, this promising new vaccine may help reduce the threat of CCHFV, although further study is needed to fully understand the immune response involved, determine efficacy of vaccine timing and describe the mechanism of protection.

“The success of this replicon particle vaccine marks a fundamental step forward in the CCHF field in the effort to find a viable strategy to combat this disease,” said Pegan.

UGA and the CDC have filed a joint patent for the new vaccine. The article, “Single-dose replicon particle vaccine provides complete protection against Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus in mice,” was published in Emerging Microbes and Infections. The study was funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.