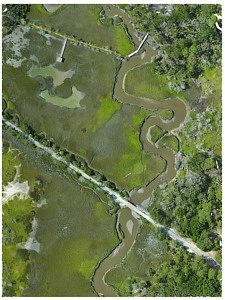

On Sapelo Island, amid the draperies of Spanish moss and quiet marshes of Spartina grass swaying in the breeze from the gray Atlantic, it’s easy to lose track of time. Beachfront development is nowhere to be seen, and the urgent jangle of civilization is replaced by wind song and the murmur of ocean lapping the shore. Months and days are measured by tides.

For 65 years, the UGA Marine Institute has lived among the past, present and future of Sapelo, becoming one of the premier locations in the world to study coastal ecosystems—salt marsh ecology, in particular. Ecology pioneer and UGA legend Eugene Odum was perhaps the first to recognize Sapelo’s potential as a research station, and many renowned scientists in the early days of ecology spent time on the island.

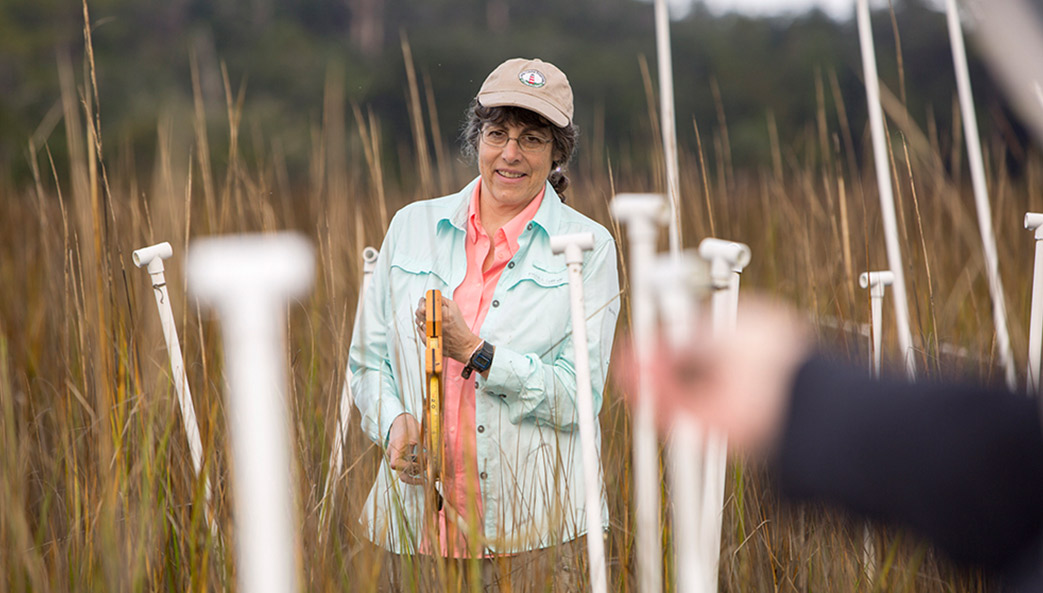

That tradition continues today with the Georgia Coastal Ecosystems project, which was recently renewed for another six years and $6.7 million by the National Science Foundation through its Long-Term Ecological Research program. Since 2000, GCE and UGAMI—both now under the leadership of Merryl Alber, professor in the Franklin College of Arts and Sciences—have tracked and evaluated data that hold clues to the workings of that vast natural system Odum described. Kicked off in January with a conference in Athens, “GCE-IV” involves 22 principal investigators from nine institutions and will run through 2024.

The Marine Institute campus was first bestowed to the university by tobacco heir Richard J. Reynolds Jr. (UGA Office of University Architects)

But the years have not always been kind to UGAMI. Alber took over as director in 2013, shortly after UGAMI moved to its new administrative home in the Office of Research. The institute’s funding was down, its facilities were outdated and in dire condition, and its future was uncertain. Then in 2017, after renovations had begun, Hurricane Irma dumped a massive storm surge on Sapelo, ruining a year’s worth of improvements.

Some leaders would have seen a crisis. Alber saw an opportunity.

Disaster response

“This is Lab 8,” Alber says, flipping through a binder of snapshots of UGAMI buildings and interior spaces. “I like to show this picture because we’ve transformed it.”

Indeed, the images tell a tale of transformation that goes far beyond Lab 8. When she and her UGA colleagues began to seriously assess the work required to renovate UGAMI’s physical plant, they were astounded at the scale of the task. There was the work they knew about—outdated electrical systems, asbestos tiling, plumbing problems, nonfunctional HVAC, a preponderance of mold—but there were also the surprises. Doors that had literally been locked for decades were finally opened, and what lay behind them was not pretty: chemicals, samples, old equipment, books, often piled floor to ceiling, none of it touched for years.

“The first year we spent just throwing stuff away,” says Jacob Shalack, UGAMI’s assistant director for operations. “No one cares about throwing trash in a closet when every closet is full of trash. You couldn’t even start renovating because there was stuff everywhere.”

And that was before the hurricane. In April 2017, UGAMI completed “Phase 1-A” of its renovations, which included a bona fide teaching lab for undergraduate courses. Two months later, UGAMI faculty taught their first class in that lab, and then in September Irma put everything underwater.

“It was so sad. So sad,” says Alber, still flipping through her binder. “Here’s what the teaching lab looked like after the water receded. There was water in all the drawers. The visitor labs were full of water. We had mold that grew very quickly; it took about a week for people to be able to get onto the island.”

But Irma’s dark clouds were definitely laced with silver. Suddenly, in addition to funds UGA had earmarked for the renovations, there was insurance money. Because Alber had already created a master plan for UGAMI’s overall revitalization, there was an opportunity to do more than simply rebuild.

“They were able to quickly deploy this plan—much faster than we normally would have been able to do,” says Carl Bergmann, associate vice president for the Office of Research.

Every dollar available for renovation was leveraged to the hilt. Alber asked for repair and renovation funding from the university. She received an NSF infrastructure grant to rebuild the system used to pump seawater through the lab. Visiting contractors stayed in UGAMI residential space, saving the university on hotel costs. Special metal barriers designed to protect against flood damage were custom built in the UGA Instrument Design & Fabrication Shop for half the $100,000 price tag of commercial products. All savings were poured back into the project.

Everyone—faculty, UGA administrators, contractors, research staff, even volunteers—worked together. When Alber put out a call for $2,000 to restore the main laboratory building’s historic clock, the Friends of UGAMIorganization raised the money in less than 24 hours. Atlanta’s Whiting-Turner Contracting Co.began holding annual work weekends at Sapelo each February, lodging about 30 employees on the island and completing whatever tasks topped the priority list. On the first such weekend, Whiting-Turner paid for several dumpsters to be barged over to the island and filled with decades of UGAMI detritus.

“It’s a win-win,” says Keith Douglas, Whiting-Turner executive vice president. “Not only were we doing something good, but it became a way for our own people to get to know each other better and bond.”

“The Marine Institute was too valuable a resource to let its physical condition continue to decline,” says David Lee, UGA vice president for research. “We had to act, and fortunately Merryl has been a great partner, providing exactly the type of leadership UGAMI needed at this time. We have also benefitted from the dedication and hard work of many others who care deeply about this unique resource.”

A new history

Richard J. Reynolds Jr., son of the founder of R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co., donated all of UGAMI’s major buildings to the university upon the institute’s founding in 1953. Lab 8—Alber’s before-and-after room—had its own story to tell. When the room’s plywood paneling was removed during renovations, the wall behind it was wallpapered with Sapelo history. Reynolds had commissioned custom paper covered with images of his family in the “big house”—what UGAMI folks call the Reynolds Mansion on Sapelo—and which remained hidden for decades.

During renovations some treasures of the past were uncovered, like wallpaper with images of the Reynolds family discovered under the paneling in a UGAMI lab. (Michael Terrazas)

Relics of Sapelo’s past pervade the institute’s grounds. There’s the famous “turkey fountain” that once ran with artesian water. There’s the auditorium that was Reynolds’ private movie theater, its art deco chandelier still hanging over original movie-style seats. There’s the old darkroom, still stocked with vintage photo enlargers and long-expired tubs of developer, and which former Georgia governor and amateur photographer George Busbee allegedly used during his visits to the island. There’s the long-rusted marine railway that once tugged Reynolds’ boats into drydock, not far from the twin carriage houses that sheltered his horses and now serve as UGAMI administrative and common space.

“This wing of this building,” Alber says, gesturing around her office, “was not finished. It was dirt floors and storage. After the flood, things had to be gutted, stripped down and dried out. We said, ‘If you’re going to gut this building and rebuild, why not change the layout and make it serviceable for what we need?’”

And what a 21st-century UGAMI needed most was flexible space that could accommodate researchers staying on Sapelo not for years but for a week or perhaps a few months, plus handle an increasing emphasis on undergraduate education. Specially equipped years ago for individual researchers, many of the institute’s old labs sat locked and dormant when those people left and no one took their place.

“A lot of the rooms were not very functional,” says Steve Pennings, professor of biology and biochemistry at the University of Houston and the chief GCE co-PI. “It’s not like a field station needs to be a high-tech, super advanced place, but you do like it to be clean and for the water and electricity and air conditioning to work.”

UGAMI’s ongoing renovations are addressing these needs and more. The lab and carriage houses are no longer shuttered; they’ve been reconfigured to meet the programmatic goals laid out in UGAMI’s strategic plan. And precautions have been taken to protect against future flooding: Electrical outlets were raised higher and casements redesigned to lift them off the floor, and the number of doors was reduced. Cement trucks were barged over to raise the floors of the carriage houses by several inches.

“Being flooded was a huge pain,” Pennings says, “but it also created opportunities to rebuild things better than they were originally.”

Coastal disruptions

On a cold, rainy day in January, a crowd gathers in a small auditorium at the UGA State Botanical Garden to learn about the typology of disturbance. Perturbations, Alber explains, can be typed as pulses, presses or ramps. Much depends on their duration and whether the system being perturbed in time shows resilience or undergoes a state change.

Disruption is the theme of GCE’s fourth life. Its nearly two dozen PIs from universities and labs across the country will examine disturbances, ranging from the collapse of a creek bank up to and beyond massive weather events like Irma, and their impact in the marshes and estuaries of the Sapelo, Doboy and Altamaha rivers.

The team will bring a wide lens. GCE produces about 40 peer-reviewed publications each year, Alber says, and its expertise now ranges beyond salt marsh ecology and biology to biogeochemistry, geomorphology, coastal geology and even physical anthropology. Associate professor Amanda Spivak, newly hired to UGA’s Department of Marine Sciences from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute in Massachusetts, will study carbon cycling and how the local terrain fits into regional and global cycles. Professor Victor Thompson of the UGA Department of Anthropology works to unearth evidence of Native American oyster fisheries and how those practices shaped the barrier island’s development.

John Schalles, professor of aquatic science at Creighton University, has been part of the project since GCE-II but his history with Sapelo goes back to the 1970s. Over that time, his research focus—remote sensing—has evolved from aerial photography and mapping to satellite imagery, and now to drones capable of capturing images in incredible resolution. He’s also watched UGAMI transform from a community of resident scientists to a more remotely connected family of users.

“It’s a big, friendly group, very collegial, very collaborative,” Schalles says. “When the older members [of UGAMI] get together, we appreciate the continuity with our past and the impressive young scientists joining our ranks. As we all take on ambitious new projects, we’re supported on the shoulders of giants—these foundational people in ecosystems ecology.”

“There’s a history of discovery at UGAMI that speaks to environmental scientists all around the world. To see this unique asset come back from the brink and, through the support of the university and its many friends, be positioned to support groundbreaking work for yet another generation has been very gratifying,” Lee says. “Also, it’s just a beautiful setting for students and faculty to do their work in.”

“When you live here, you get really tuned to the tidal cycle and the lunar cycle,” Alber says. “It just becomes part of you.”

Indeed, for all its ups and downs, UGAMI’s history has always kept researchers coming to Sapelo, and the island never lost its ability to enchant.

“There’s a history of discovery at UGAMI that speaks to environmental scientists all around the world. To see this unique asset come back from the brink and, through the support of the university and its many friends, be positioned to support groundbreaking work for yet another generation has been very gratifying,” Lee says. “Also, it’s just a beautiful setting for students and faculty to do their work in.”

“When you live here, you get really tuned to the tidal cycle and the lunar cycle,” Alber says. “It just becomes part of you.”

Indeed, for all its ups and downs, UGAMI’s history has always kept researchers coming to Sapelo, and the island never lost its ability to enchant.

“When I got there [in 1979], we had on the order of 10 to 12 resident faculty on the island,” says Chuck Hopkinson, UGA professor of marine sciences, who now teaches a course on the island each summer. “We had a lot of people coming from overseas who just had to come and pay homage to Sapelo because of the reputation of all the work that had been conducted there.”

“Spending time here is life-changing for many of our students,” says Damon Gannon, assistant director for academic programs. UGAMI’s summer semester for undergraduates now has a waiting list six months in advance, and Gannon is working to start a spring program.

“My time on Sapelo was a magical experience,” says Hakon Jones, a senior ecology and biology major. “I found 37 shark’s teeth on the beach and even managed to spot a female loggerhead heading back to the water on a full moon night at 3 a.m. Living on a protected island that so few get to see, with the close proximity to wildlife and the atmosphere of the salt marsh all around you, is something every student interested in being outdoors would find breathtaking.”

Since she took over as director, Alber has emphasized the field station part of its mission. “We do not have year-round resident scientists any longer, but we are a really, really good field station that supports a robust research agenda and a growing educational program,” Alber says. “Visitors are amazed at what we’ve been able to accomplish in terms of the facility, and we are continuing to work on it. I’m very optimistic about the future.”