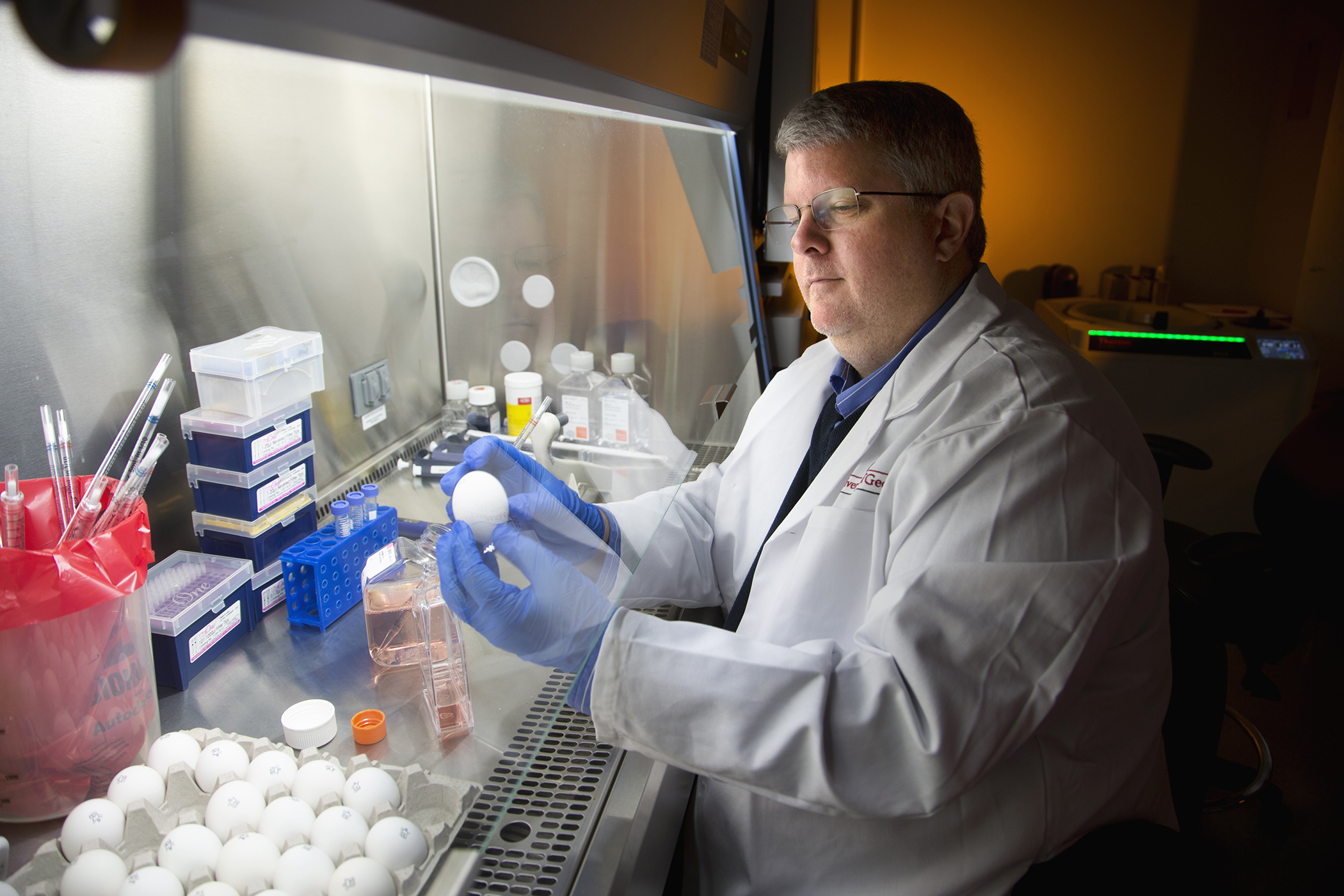

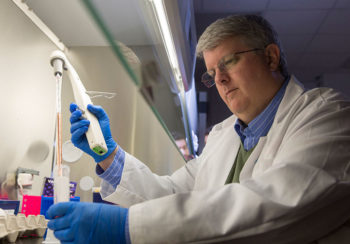

Ted Ross joined the University of Georgia College of Veterinary Medicine this year as the Georgia Research Alliance Eminent Scholar in Infectious Diseases and as the director of a newly formed Center for Vaccines and Immunology. His laboratory develops and tests vaccines for a variety of viral diseases, such as influenza, dengue, respiratory syncytial virus, Ebola and HIV/AIDS. Here, he discusses the future of vaccine development in his lab and across UGA.

Ted Ross joined the University of Georgia College of Veterinary Medicine this year as the Georgia Research Alliance Eminent Scholar in Infectious Diseases and as the director of a newly formed Center for Vaccines and Immunology. His laboratory develops and tests vaccines for a variety of viral diseases, such as influenza, dengue, respiratory syncytial virus, Ebola and HIV/AIDS. Here, he discusses the future of vaccine development in his lab and across UGA.

Your lab is developing a number of different vaccines for a variety of diseases, but you are particularly interested in influenza. How is your influenza vaccine different from what people get every year during the cold and flu season?

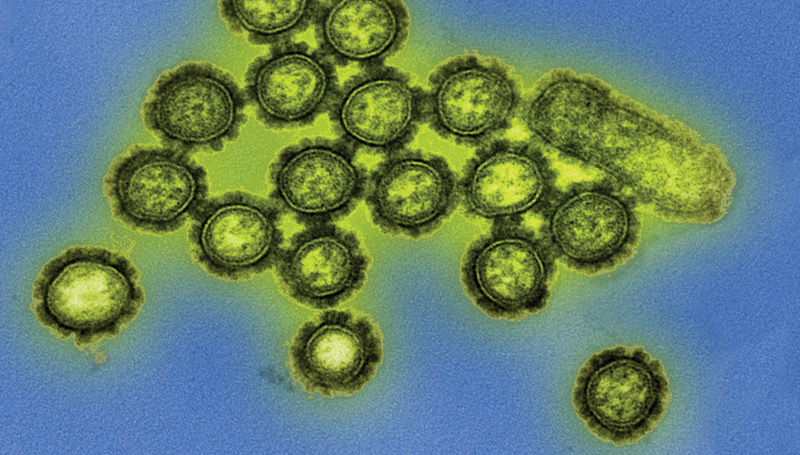

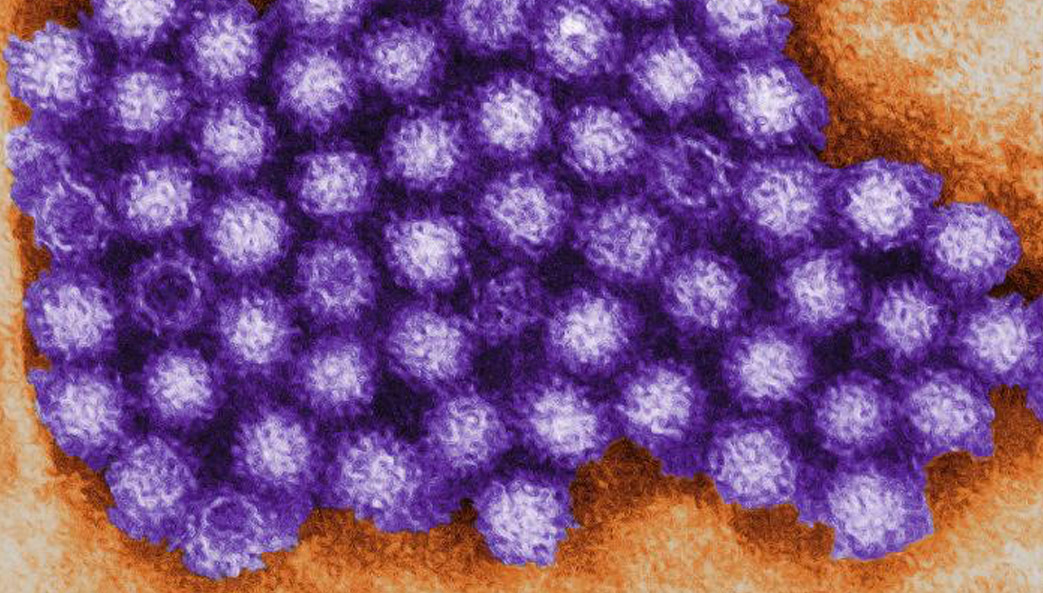

There are many different strains of influenza that affect humans, and the flu shot we get is based on predictions about which strains are going to be most prevalent. What this means is that we have to change the vaccine every year, but it can’t protect you from all forms of flu. What we’re developing is known as a universal vaccine. Basically, this is a vaccine that recognizes all the influenza virus strains that are circulating out in the population now, but also those that may appear in the future. A universal vaccine would mean that people would no longer have to get an annual flu vaccine; it would be much more like what we have for polio, smallpox or mumps, where you get one or two shots and you’re protected for many years or even a lifetime.

Does this vaccine only work on seasonal influenza?

No, the idea is that this vaccine would protect against all forms of influenza, including those that aren’t associated with seasonal flu. We actually began our research about 10 years ago by focusing on H5N1 influenza, more commonly known as bird flu. This was causing a lot of disease in humans at the time, and people were concerned about the possibility of a new pandemic. But it also raised a big question: how do we deal with a strain of influenza that we don’t yet know exists? Could we generate a vaccine that protects against all strains of H5N1? My lab generated a universal H5N1 vaccine in 2008, and we’re still testing to see if it protects against infection. So far, our vaccine is working, even against the newer strains of today.

What are the next steps for your vaccine platform?

We currently have a universal vaccine based on H1N1, which people may know better as swine flu. We’ve licensed this vaccine to Sanofi-Pasteur, and our goal is to begin clinical trials in 2016–2017. From there, the vaccine will move into larger scale testing to see if it can protect against all the other influenza subtypes that affect humans. It will take a while, but it could serve as the foundation for a universal influenza vaccine.

You’re also leading a new center at UGA focused on vaccines. What do you think the future holds for vaccine development here at the university?

Yes, it will be called the Center for Vaccines and Immunology, and our broad goal is to better understand the fundamental science of vaccines and immune responses. If groups from the center bring new vaccines to the marketplace and they get licensed, that’s great, but we want to conduct basic science that will help us understand the immunology of infectious disease and how vaccines work in different populations depending on their age, gender or race. We also want to know more about the role of genetics and why people react differently to vaccine formulations so that we can construct vaccines that work well in as many people as possible.

Ultimately, where do you hope this research will take us?

Everything we do in the center, from basic to applied science, will focus on translating what we’ve learned to new vaccines for humans, as well as veterinary animals. Researchers from many different parts of campus will be working as part of the center to find new ways of combating a number of dangerous pathogens. We also want to develop new vaccines for animals, from poultry to household pets. But we’re not going to do this alone. We have to think about these problems globally, so we will have a number of partnerships with colleagues here in Georgia and across the world.

Finally, there’s a lot of talk right now in different forums about vaccines, and not all of it is positive. What’s your message to the skeptics?

Vaccines are one of the most important developments in the history of humankind. We have eliminated or reduced the incidence of many of the most deadly infectious diseases because of vaccinations, and we have some distance from those diseases now because vaccines have been so effective. I think a lot of people forget what the alternative is. Any drug, including vaccines, will have side effects, and scientists go to extraordinary lengths to make sure that adverse reactions are rare. It can take more than 20 years for a vaccine to get approval, and it must go through a number of rigorous safety and efficacy trials before it reaches the marketplace. Ultimately, though, the diseases that vaccines prevent will do far more harm than anything a doctor puts in your arm.