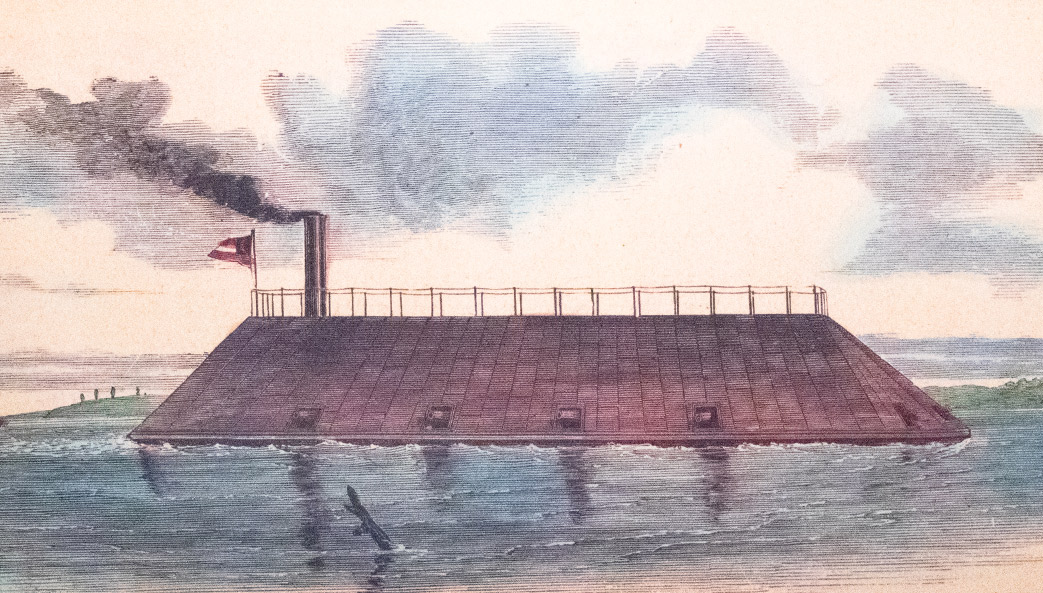

In the waning days of the American Civil War, as General William Tecumseh Sherman neared the completion of his fabled “March to the Sea,” Confederate soldiers in Savannah scuttled the gunboat CSS Georgia to keep it from falling into Union hands.

In truth, the 1,200-ton Georgia was a gunboat in name only, as its steam engines were too weak to propel the hulking ironclad ship through tidal waters. The Rebels anchored the warship and used it as a floating battery to protect the harbor from Union naval advances, but it sank to the river’s bottom in 1864 having never fired a shot in battle.

And it was there, in the briny depths of the Savannah River on the Georgia-South Carolina border, that the Georgia would remain, mostly forgotten, for over 150 years. But interest in the gunboat was recently renewed when plans to dredge the river’s shipping channels, as part of the Savannah Harbor expansion, meant that workers would have to excavate near the Georgia’s watery grave. Enter the Army Corps of Engineers, which hatched a plan to salvage as much of the old warship as they could.

Navy divers working on the project found a treasure trove of Civil War-era artifacts alongside the ship’s remains, including scraps of clothing, sword hilts and cannons, even the ship’s propeller still attached to its shaft. The divers also found something that was cause for concern: more than 170 artillery rounds that, despite having been exposed to the corrosive salt water for more than a century, remained largely intact—and explosive.

Making the munitions safe to handle

Historic preservationists who wanted to display the shells in museums and at conservation societies needed a way to render the ordnance safe, and their search for help eventually led them to MuniRem Environmental, LLC, a company—founded by Valentine Nzengung, professor of environmental geochemistry at UGA—that specializes in the neutralization of explosives and chemical warfare agents.

The company’s eponymous core technology MuniRem, which Nzengung created in 2005, is a chemical mixture that, when applied directly to explosives, renders them non-hazardous.

“Once MuniRem comes in contact with energetic materials, it immediately begins a chemical reaction that can neutralize the explosive in seconds,” said Nzengung. “There are other chemical means for neutralizing explosives, but they mostly end up with hazardous waste. Because the byproducts of the MuniRem reaction are completely nonhazardous, it is also a green technology.”

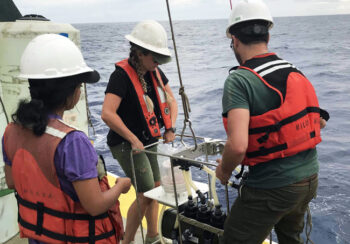

Nzengung and a team of engineers and technicians brought an ample supply of MuniRem to the banks of the Savannah River, where they custom-built a mobile munitions-neutralization facility and began the delicate process of making each artillery projectile safe to handle.

The Army Corps delivered the explosives—a mixture of 6.4-inch Brooke and nine-inch Dahlgren projectiles, each weighing between 57 and 87 pounds—with each munition contained in a bucket of river water. Unlike the rounded Dahlgren, which resembled a traditional cannonball, the bullet-shaped Brooke shells were designed as armor-piercing rounds, and they were fired from a rifled cannon.

The first step in making these rounds safe was to drill a small hole in the side of each munition so that workers could gain access to the black powder trapped inside. “For MuniRem to work, it must make physical contact with the explosive material,” Nzengung explained. “So we developed a drilling apparatus that allowed us to get it inside the shells while still keeping the artifacts intact.”

After clearing the site of all other personnel, MuniRem Environmental ordnance experts Ben Redmond and Matt Christiansen placed each munition in a metallic box filled with water to reduce the risk of sparks once the team began drilling. They operated the drill from a safe location behind a steel blast screen, using an iPad and GoPro camera to observe the process from a distance.

People on the project were soon impressed with the ancient munitions’ durability. “I was amazed by how well preserved these projectiles were; it was almost like they had been made yesterday,” said Redmond, a retired Marine Corps explosive ordnance disposal master technician and senior technical consultant for the project. “The powder in a lot of these shells was bone dry.”

Not your normal day at the office

Once breached, the shells were quickly moved to another station where Stephen Pilcher, the project manager, flushed their interiors with warm MuniRem solution pumped through a high-pressure nozzle. The black powder slurry that ran out of the shells then traveled down a wooden sluice box (similar to what gold miners use) into a drum containing MuniRem.

Again, the Confederate munitions makers earned the modern-day team’s respect. “The powder inside these shells was packed very tightly,” said Pilcher. “We had to break it up with the pressurized water to make sure that the MuniRem could reach all the explosive material.”

From there, the shells moved down the line, where project engineer Spencer Nzengung sprayed the interior of the munitions with a mixture of water and MuniRem using a small rubber hose. After flushing each shell several times, they were then moved to a tub to soak in a MuniRem bath for several hours. “The soak ensured that every last trace of explosive powder would come in contact with the MuniRem,” said Nzengung.

In the final stage of the process, Redmond and Christiansen removed the fuses at the tip of the Brooke shells and treated them with MuniRem as well. The fuses contained a pressure-sensitive detonator that, when the shell hit its target, would initiate a small charge into the main body of the shell to trigger detonation.

“There is still a chance of a small explosion from the fuse if it were dropped or hit with an object,” said Christiansen. “It’s obviously not as dangerous as a shell loaded with black powder, but we treat them with respect, and with MuniRem, to make sure they can’t detonate.”

With the shells fully treated, the MuniRem crew transferred custody of the munitions back to the Army Corps, which passed them off to the team of archaeologists from Texas A&M University leading the preservation effort. The fully neutralized shells will soon be distributed to various locations throughout the country for history buffs to enjoy in person.

“It was a remarkable experience to be so close to these pieces of history,” said Redmond. “This isn’t your normal day at the office.”

“It’s all just reduction chemistry”

Indeed, working on the munitions from the CSS Georgia was an unusual experience for all the members of the MuniRem Environmental team; they are not normally in the business of historic preservation. Actually, when Valentine Nzengung first started experimenting with this technology, he wasn’t dealing with explosives at all.

“Before I developed MuniRem, I was working on a method to remediate solvents used in the dry-cleaning business,” Nzengung said. “These chemicals can contaminate groundwater, so I wanted to see if we could develop a method to make their wastes safer.”

Shifting from dry-cleaning waste to explosives may seem like a dramatic jump, but Nzengung doesn’t see it that way. “From my perspective, it’s all just reduction chemistry,” he said. “I ask myself ‘What chemical bonds exist between a substance’s elements and how can I break them down to turn it into something else?’”

Nzengung started in explosives remediation when he worked on a project for the U.S. Department of Defense to remediate soil contaminated with perchlorate, an oxygen-adding compound used in the manufacture of solid rocket fuel. “As a university researcher, it can be difficult to get your hands on explosives for scientific testing, but suddenly I was surrounded by it,” Nzengung said. “That project is what allowed me to develop the early predecessors of MuniRem.”

And after many years of careful study, he was able to take the technology from a small side project to the foundation of a successful business. With the help of UGA’s Innovation Gateway, which assists UGA researchers in the translation of ideas and discoveries into commercial products and services, Nzengung established business relationships with a variety of organizations that needed green and—just as important—cost-effective ways of dealing with explosive materials.

MuniRem Environmental recently contracted with the U.S. Department of the Army, for example, to develop portable kits to neutralize small quantities of nitrocellulose- and nitroglycerin-based propellants and explosives that occasionally wash up on Hawaii’s beaches. The propellants are legacy munitions from World War I & II, the Korean War and the Vietnam War that were dumped at sea.

In another contract with an industrial client, Nzengung’s company helped decontaminate the equipment and buildings at the former Louisiana Army Ammunition Plant, which used an explosive compound called H-6 in its manufacturing processes. In this project, the manufacturing equipment and even the building itself needed to be decontaminated.

“In munitions factories like this, small amounts of explosive material collect in the cracks and crevices of the machinery and even on the walls and floor of the facility,” Nzengung said. “We sprayed down the machines and the building with a MuniRem-and-water solution to neutralize these chemicals so that demolition could proceed safely.”

Nzengung also contracted with the Australian Department of Defense to neutralize a large chunk of TNT that had accumulated in a pipe at a former military munitions-production plant. Having traveled to the site, MuniRem Environmental workers flushed the pipe with a MuniRem solution, allowed it to pool on top of the caked TNT, left the mixture to soak for 18 hours and then flushed again. After inserting a camera into the pipe to confirm that all of the TNT had been neutralized, the workers collected the wastewater and treated it again with MuniRem to ensure that all the explosive materials had been destroyed.

The fruits of tenacity

Nzengung continues to refine his invention in his UGA laboratory and, where indicated, to commercialize the results. “We can now formulate MuniRem to neutralize almost any explosive material, from the black powder that we found in the artillery shells of the CSS Georgia to more advanced modern explosives and chemical warfare agents,” he said.

Creating a new product and moving it into the marketplace is a difficult process, but Nzengung’s tenacity was unwavering. “It has taken me from 2007 to now to convince potential clients that our product works, and they are starting to take notice,” he said.

The University of Georgia has taken notice as well. This spring Nzengung was named Academic Entrepreneur of the Year in recognition of his achievements both in science and business.

About the CSS Georgia

The Ladies’ Gunboat Association raised $115,000 in 1862 (more than $2 million in today’s currency) to construct the CSS Georgia.

Its ironclad armor was fashioned from railroad irons because the South lacked sufficient foundries to press enough steel into plates.

The Georgia’s mission was to guard against Union naval advances into Savannah, but it never fired a shot in battle except for an unconfirmed volley against a Union rowboat.

The U.S. Navy still classifies the Georgia as a captured enemy vessel.

A map commissioned by General William T. Sherman after the fall of Savannah in 1864 showing Confederate defenses in red. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)