It was a simple prompt posed to the now ultra-popular program ChatGPT:

“Could you provide a list of 10 suggested questions to ask AI experts about ChatGPT and its potential impacts on society, both good and bad?”

A flashing black square indicated the program’s “thoughts” for about three seconds, and then words began to hastily appear on the screen. Like an overexcited novelist unloading thoughts onto the page before they were forever lost to forgotten synapses in the brain, the computer program crafted a carefully worded list of questions for an upcoming roundtable discussion on artificial general intelligence.

A few questions were basic. Others were much more complex and reflected a humanlike social awareness.

The program—and other similar automated models—have entered the public consciousness in great earnest in 2023. While artificial intelligence has long been a discussion, never has its potential disruption in all corners of society been felt more acutely.

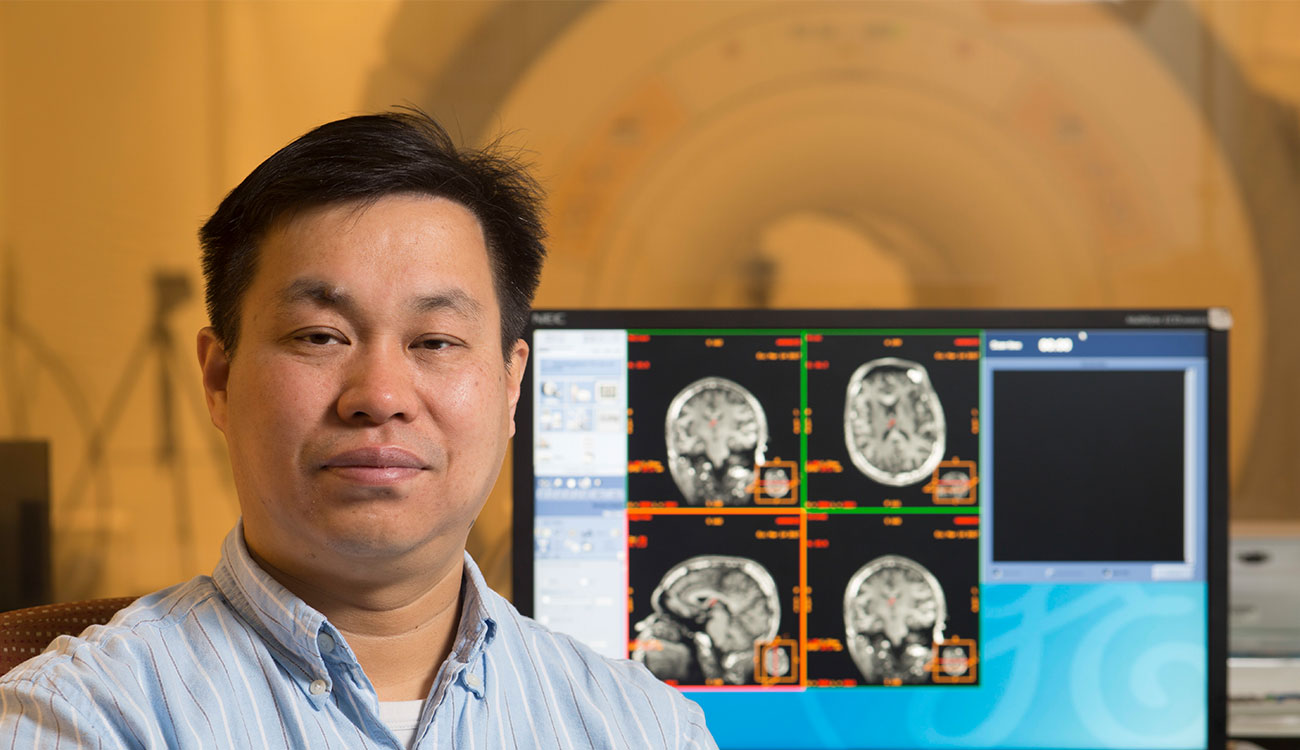

The University of Georgia’s Office of Research communications team spoke with two experts—Associate Professor John Gibbs (Department of Theatre & Film Studies and the Institute for Artificial Intelligence) and Distinguished Research Professor Tianming Liu (School of Computing)—about the autonomous program that has ignited public discourse.

Research Communications (RComm): Artificial general intelligence (AGI) and ChatGPT are popular but complex topics for the average person. Can you give a little background?

Tianming Liu: We’ve known about artificial intelligence for years. For traditional AI, people use a specific dataset and train a specific model for a specific task. AGI is completely different. General intelligence means that we have the same foundational model that can be used to detect anything—a cat, a dog, a human, whatever. It is one model for everything. That’s a very important difference.

Secondly, in the traditional approach, we need to train it. That’s why we need a lot of training data for a very specific question or problem. It’s a big burden for people to have to do the annotation for each application. The zero-shot application—or a training method that allows a model to classify objects without being trained on those specific objects—in AGI is super powerful.

RComm: Is this why it feels like the timetable on AI has sped up so much in the past 12-18 months?

John Gibbs: Let’s take it up a level. GPT stands for Generative Pre-trained Transformer. Generative means it must generate something, and pre-trained is just a huge Excel spreadsheet with a lot of numbers in it. And the magic is that you train this on all the words in the entire corpus of human history, and it generates the next word and then the next word and so on. It’s doing this on its own, so you don’t have to have human beings in the loop. It does this trillions of times until it gets really good.

While it seems similar to Siri, to do so many things—whether that’s writing Python code or writing a poem or a story—ChatGPT must have predictive power, and that’s what’s so amazing. It has reasoning, and that’s unexpected. It’s an emergent property of the complexity of this thing, sort of like a human brain in the sense that it learns how language operates. That is world changing.

RComm: Growth in this area has been exponential. Is it reasonable to expect it to continue at this pace?

Liu: I think it will. This depends on society’s response, of course. For example, over 1,000 people issued an open letter to stop training GPT-5. There will be some resistance because this is uncharted territory, and it’s a dialogue between two sides. Some believe we are going too fast and need to slow down, while others say the government should enact some regulations or laws regarding ethics. This is a healthy discussion. This will impact everyone’s life.

RComm: Many are concerned these advancements could impact things like their jobs. Should I as a writer, for example, be afraid that ChatGPT is going to take my position?

Gibbs: It’s a serious question and a concern. The flip side is that maybe you could easily become five to 10 times more productive. I’ve started novels but never finished because it’s a big slog. Now, I have a writing assistant and I can tell it what to write and then go back and edit. But it speeds up my ability to create.

The problem is that where you might initially need a shop of 10 writers for your company, now you can have just two. Many in the creative space might lose their jobs because you can do it efficiently with fewer people.

RComm: We decided to test how well ChatGPT could do our job and had it create a list of interview questions. We’ll let it take the next one.

ChatGPT: How concerned are you about the potential misuse of ChatGPT technology such as its potential to spread disinformation, generate fake news or deep fakes, or facilitate malicious activities like cyberattacks?

Liu: My collaborators and I just published a paper in which we wanted to detect whether a sentence was generated by ChatGPT or not. We could do this at 97 percent accuracy. We need to be able to distinguish, and then we can check to see whether it’s accurate and responsible or not. I think we can do this in a technical way. We can check to see whether a paper, for example, was written by a student or not and put a policy in place that students must follow.

RComm: You brought up ChatGPT and the academic space. How should administrators and faculty approach the changing nature of academics?

Gibbs: In early January, I asked my basic creative writing class how many had heard of or used ChatGPT. Half the class of 30 said they had. By a couple of weeks later, that number was 100 percent. Then I talk to faculty, some of the most technologically advanced faculty who are very much at the forefront of using new tools, and they all pretty much uniformly said, “Absolutely not. This shouldn’t be allowed.” But I think we should deal with the reality. I’m old enough to remember when we got calculators in the 1980s, and teachers said you weren’t allowed to use them. Over time, that changed. We don’t need to be saying, “No, no, no. Don’t let it happen.” It’s already happening. The question is how do we use it to our advantage?

RComm: How about one more question from ChatGPT?

ChatGPT: How might ChatGPT technology impact the mental health and wellbeing of individuals, particularly those who may become overly reliant on it for companionship or emotional support?

Gibbs: That question came from ChatGPT?

RComm: It did.

Gibbs: Wow, what a fascinating question. There haven’t been many statistical surveys, but there are people who are very sad because—and it’s often job focused—they have been doing a job for years and find fulfillment in doing that job, and now ChatGPT can do it for them. Maybe they feel obsolete, and they are afraid and sad.

Liu: We can possibly build ChatGPT into a digital psychologist or psychiatrist. I have a friend who started a company during the pandemic using a chatbot to communicate with people dealing with mental health problems like depression or anxiety. After the pandemic, the rate of people with mental health challenges increased dramatically. And it’s very difficult for psychiatrists to keep up. So, is this a case where we can use reinforcement learning from human feedback to train ChatGPT into a personalized psychiatrist? That could be effective. Not a replacement, but an assistant that can help people deal with their challenges.

Gibbs: I have a very good friend and brother who are both counselors. It’s tough to say a model could ever do what they do, but on the other hand there aren’t nearly enough counselors. At 3 a.m. maybe you could fire up your “PsychGPT” and it’ll be there for you, as opposed to a human who works on a schedule.

RComm: This is a paradigm shift for the way information can be created, shared or expressed. What’s your final message for how we need to proceed on a shared path forward?

Liu: We as faculty, presidents, provosts, vice presidents for research—all of us—need to have a discussion. I was on the Provost’s Task Force for Academic Excellence a few years ago. We had many meetings, one every two weeks. We can start a conversation here, maybe even within the Office of Research. If we come together and create a shared vision, perhaps we can generate some momentum in getting in front of these challenges.

Gibbs: I also think we can leverage the faculty. The Institute for Artificial Intelligence has only a couple full-time faculty assigned to it. Everyone else is in a halo of faculty who work with artificial intelligence. It’s maybe 60 or 70-plus faculty members, maybe more. That’s a lot of people in different departments. By utilizing that group of people, you have a core who are already in various areas throughout the university, and we can build that connection with each other.