Sarah Shannon can trace her interest in the impacts of incarceration on communities to her work with a nonprofit employment assistance agency. She witnessed first-hand people with criminal records struggling to reenter their communities post-incarceration. For them, simply finding a job or a place to live was a challenge.

When she began working on her doctorate and needed a topic to study, Shannon remembered the experience.

“My work focuses on incarceration, but I also study other punishments like fines, fees and probation, as well as the collateral consequences of having a criminal record—voting restrictions and difficulty finding employment,” said Shannon, a Meigs Distinguished Professor in the Franklin College of Arts and Sciences Department of Sociology and director of the Criminal Justice Studies program.

Prison demographics and statistics have drawn plenty of headlines over the years—not to mention much social and political activism—but Shannon noted the relative dearth in attention paid to rural jails. While incarceration rates in urban areas have dropped recently, rural communities have seen the opposite.

Shannon wanted to know why.

“Jails serve as a sort of ‘catch all’ for community problems, including crime but also health issues like drug use and mental health challenges,” she said. “We know a lot about incarceration in state and federal prisons but far less about how jail incarceration functions at the local level.”

Funded through a grant from the Vera Institute of Justice, Shannon led a group of interdisciplinary researchers to fill this gap. What were the criminal charges behind the higher incarceration rates? What did those trends say about policy in local communities? And how could a better understanding of rural crime lead to better outcomes both for law enforcement and individuals leaving the system?

Big numbers, smaller crimes

It’s important to note the difference between jail and prison. While prisons house people sentenced to a year or more for felony convictions, jails are facilities that house people pretrial or on probation violations, as well as a smaller number of people serving local (misdemeanor) sentences.

For the project, researchers took administrative jail data and looked at how different factors—arrests, charges and bail—affected the jail population.

“We wanted to look at not only jail population on a day-to-day basis, but also the demographics of the jail population and the types of charges people are facing or the extent to which people are there for pre-trial or probation violations,” Shannon said.

The team partnered with facilities in Decatur, Early, Greene, Habersham, Sumter, Towns and Treutlen counties, analyzing logs between January 2019 through June 2020.

In addition to Shannon, the team included School of Social Work Professor Orion Mowbray and co-principal investigator Dr. Beverly Johnson from the Carl Vinson Institute of Government.

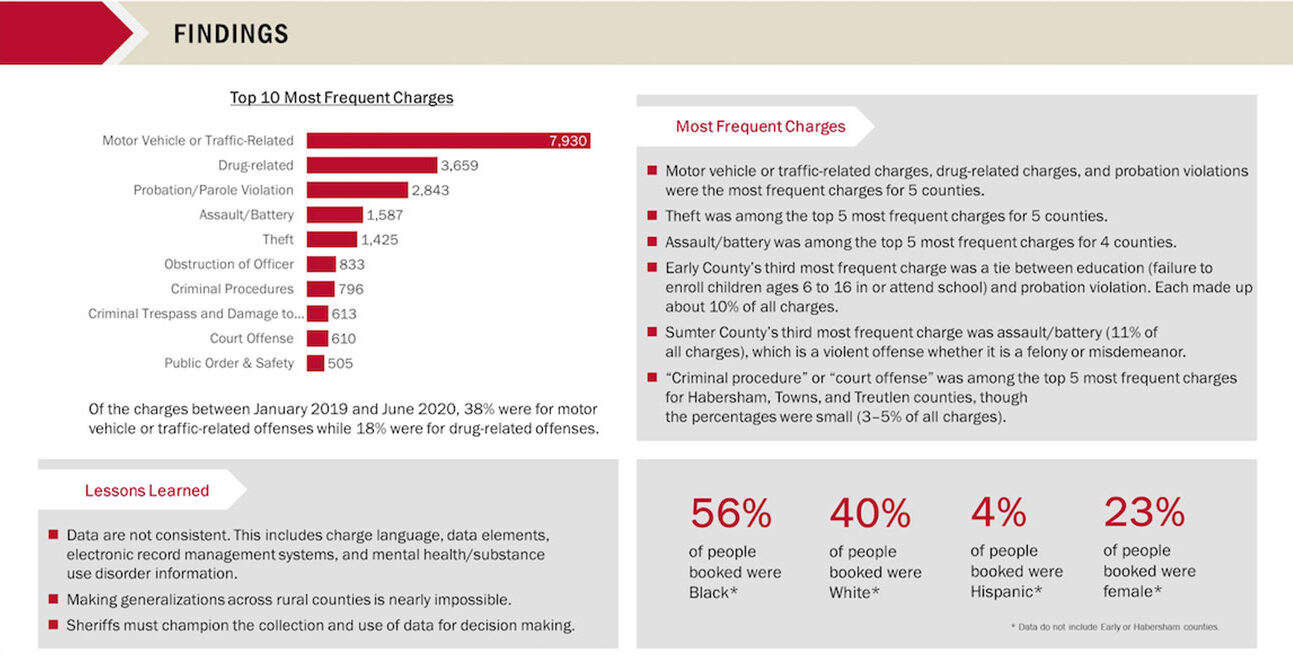

They found that the top charges were minor traffic- or drug-related offenses, and probation or parole violations.

“Many communities in Georgia, while different, tend to experience the same issues as it relates to drug and alcohol-related crime,” Mowbray said. “For example, in counties that participated, driving under the influence (DUI) and drug possession were consistently two of the top eight reasons persons were incarcerated.”

Minor traffic-related incidents, such as driving on a suspended license or failing to stop at a traffic control device, made up 38% of jail bookings across all seven counties. Drug-related offenses also showed up frequently in the data, about 18% of the total bookings analyzed in the project. Parole and probation violations are among the top three charges seen in rural jails, totaling just under 3,000 arrests.

“Georgia is the leader nationally in probation supervision, so it wasn’t necessarily surprising to see that,” Shannon said.

Notably, charges that some consider more egregious—assault, battery and theft—were less commonly seen. Shannon noted that most of the assault and battery charges were associated with family violence.

COVID-19 impacted the bookings starting in spring 2020. Many experts in Shannon’s field questioned if the pandemic would be an opportunity for state and local jails to reduce incarcerated populations in more lasting ways. Instead, they saw a quick rebound after the first two months of the pandemic.

“This was seen nationally, but there was a substantial dip in jail bookings, particularly in late March and April 2020,” Shannon said. “But quickly, in May and June, we saw an uptick again.”

Several news reports at the time said law enforcement officers were making decisions about which kinds of charges they would issue a citation, instead of booking people into jail during those months.

It’s a (very) minor hint at the types of policy and enforcement changes researchers think could make lasting impacts.

Making sense of the data

As state and federal policymakers address efforts regarding mass incarceration, Shannon stressed the importance of considering local trends as well.

“We need to know what’s driving these trends in order to be able to devise policy solutions,” Shannon said. “The data we collected from seven rural sheriff’s offices in Georgia are very hard to come by. There are no national data sets that contain detailed information about the characteristics of people who are incarcerated in local jails, including demographics, charges, length of stay and other potential drivers of rural jail incarceration.”

Researchers met with local stakeholders, including sheriff’s office employees, local attorneys, judges and even some county commissioners to educate the community about some of the trends they uncovered in hopes of finding solutions. They also have made reports publicly available.

Mowbray has applied the findings to his own research on promoting mental health services and understanding differential outcomes associated with mental health services utilization.

“In nearly every county in Georgia, there are more beds for persons with psychiatric issues in jails and prisons than hospitals,” he said. “In many communities, sheriffs and local police departments are the de facto mental health providers.”

According to Mowbray, there is rarely follow-up between jails and public mental health providers to ensure persons referred for treatment receive that care once they’re released. This can create a compounding cycle that prevents adequate mental health care for persons involved in the criminal justice system.

Greene County Sheriff Donnie Harrison said they know jail is not a long-term solution regarding mental health and drug use.

“We try to help them while they’re here and get them on the right medication, but once they’re out on the street, they’re often on their own,” he said.

While Harrison and his team at the Greene County Sheriff’s Office would like to better address these issues, they find themselves lacking enough resources like funding and personnel, a trend seen throughout rural jails in Georgia.

Shannon suggested that changing how funding is utilized could be one approach to overcoming these challenges. Using jails as a temporary solution for health issues, for example, is both fiscally and socially costly to local communities, resulting in more incarceration and greater burdens on law enforcement agencies.

Despite a lack of immediate solutions and policies, Harrison noted that he shared results of the study with local government officials and community members to spread awareness.

“It’s really beneficial for people to understand what’s going on around them and to know what’s happening locally,” Harrison said.

“We need to know what’s driving these trends in order to be able to devise policy solutions. The data we collected from seven rural sheriff’s offices in Georgia are very hard to come by.”

– Sarah Shannon, Meigs Distingished Professor

in the Franklin College of Arts and Sciences

Director, Criminal Justice Studies Program

Education from the inside out

Shannon’s work has spread beyond classrooms at UGA to inside the walls of the Athens-Clarke County Jail through the Inside-Out Prison Exchange Program, where she has taught a course since 2017.

The class is composed of 15 UGA students, referred to as “outside” students, and 15 people who are incarcerated, referred to as “inside” students, all of whom participate in a semester-long, in-depth conversation about criminal justice policies.

Through facilitated dialogue and active learning, Shannon’s course creates a powerful and transformative learning environment for all participants. Students, whether “inside” or “outside” read the same texts, complete the same assignments and participate with equal status in the classroom.

The course culminates in a group project where all students collaborate to address an issue of concern that emerged from class discussions.

In spring 2023, students decided to produce a digital magazine filled with artwork, poetry, essays and other creative works to convey the common humanity that students discovered amongst themselves despite different walks of life. They hope it can help others reconsider how they view people “behind bars.”

Since spring 2017, 94 outside students and 57 inside students have completed the Inside-Out program through the UGA Sociology – Clarke County Sheriff’s Office partnership. Many more inside students have taken some portion of the course before being released.

Inside-Out is an international program, and classes have been taught at over 350 colleges and universities nationwide and in several other countries since 1997. More than 60,000 students have taken Inside-Out courses hosted by over 200 correctional institutions, including county jails, state prisons, federal prisons, juvenile facilities, and community correctional facilities at all security levels.