A couple of times a month, Charles Easley gets contacted by someone who’s facing infertility and looking for options. It makes sense. His research explores various causes of infertility, and he’s developing stem cell therapies to treat it, so when he publishes a new paper, people often reach out.

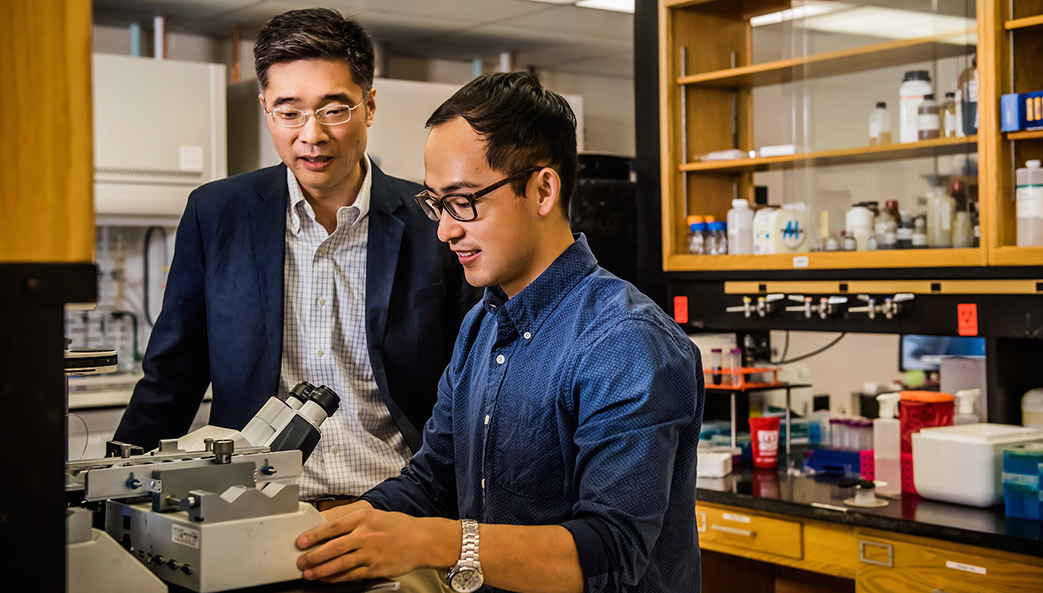

Easley always responds. The associate professor in UGA’s College of Public Health, also a member at the Regenerative Bioscience Center, considers it his duty as a scientist conducting research that’s federally funded. In this interview, Easley discusses his research and its potential for changing the lives of so many would-be parents.

Q: How do you explain your research to someone who’s not a scientist?

A: I used to spend a lot of time on Capitol Hill, meeting with members of Congress to encourage them to support the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation and increase budget funding. So I’ll dust off my elevator speech.

A growing problem in the U.S. and all over the world is that the number of cases of kids with cancer is growing. We’ve gotten much better at treating the cancer, and the survival rate for certain types of pediatric cancers is about 85% now. However, some of the treatments can cause permanent infertility.

With my research, we want to figure out a way to help patients that have no treatment options for infertility. We take skin cells, reprogram them and turn them into stem cells, and then turn them into what we call spermatids, or sperm-like cells. Then we look to see if they can fertilize an egg, which would allow males to have their own offspring.

Q: How did you get interested in this type of research?

A: When I was a postdoctoral fellow, the idea of taking skin cells and turning them into an embryonic-like pluripotent state that could become anything in the body was just taking off. The question was, “What can we turn these cells into?” Because in theory, we could turn them into anything. And the lab I was in was really focused on whether or not we could turn them into sperm cells.

I got extremely lucky. I tried a bunch of different things that failed, but then a certain combination, developed when working with other collaborators, worked like a charm. I was just trying to make stem cells that ultimately give rise to sperm (called spermatogonial stem cells). That would allow us to transplant cells back into the testes to potentially restore fertility. But as luck would have it, I was also making more advanced cells. We originally published that work back in 2012 using human cells, but we were unable to assess whether the spermatid-like cells could fertilize an egg. In the work that we just published—using embryonic stem cells from rhesus macaque monkeys to generate spermatid-like cells—we showed that we could fertilize a rhesus macaque egg with the spermatid-like cells we generated in a dish. It was the first time anybody had done that with something higher than a mouse.

Q: Are there other causes for infertility that you’re exploring?

A: Sperm counts have declined in human males over the last 40 years, and nobody has a clue as to what’s causing it, but we’re evaluating the impacts of several types of environmental exposures. We published a paper last year that showed that exposure to a now-banned flame retardant can alter the epigenetic code in sperm, potentially leading to major health defects in children of exposed fathers.

In that study, we fused epidemiological data from a cohort that had this massive exposure event in Michigan, back in the ’70s, and then we looked at the effects on their sperm. It wasn’t causing genetic effects or loss of sperm, but it was causing changes in epigenetics in sperm. In addition to showing that the exposure caused the change, we were able to use our in vitro model to identify the mechanism by which it occurred.

It was the first time an epidemiological approach had been fused with a lab approach to identify how environmental exposures contribute to health and reproductive health impacts. We’re working on a similar study with a couple of other chemicals but haven’t published any of that work yet.

Q: Is chemical exposure a problem?

A: How much we get exposed to depends on where you live, but there are some chemicals that are ubiquitous because of how much they were used. For example, the PFAS chemicals [per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances] were and are widely used all over the world because they were considered harmless for a long time. They get in the water, they’re persistent and they don’t break down. They’re everywhere. Over 95% of Americans have detectable levels in their bodies.

Age also plays a role. If you sample my mom versus me, the mixture may be different because some of the chemicals she was exposed to may have been phased out before I got to the point of being exposed.

When I first got into this field, I wasn’t trained in environmental health science. But I got an NIH/NIEHS K22 grant designed to encourage people from other fields to bring novel techniques and models into environmental health science, and I had to take a couple of classes as part of my training. When I first started learning about how much stuff we get exposed to, I thought, “I just want to go live in a bubble,” but that’s not realistic.

Q: What’s it like to hear from people who are struggling with infertility?

A: It always stings a decent amount, but even more so now because my wife and I had our first child this year. I got an email in October from a man who had leukemia and spent most of his childhood in hospitals hooked up to IV machines and going through chemo. He beat the cancer, but then as an adult realized that he couldn’t have a child. It’s devastating for people in that situation—it affects their relationships and their mental health.

When I read that particular email, I happened to be holding my son—who was less than 2 months old—in my arms. It hit me harder, and all I could think was, “This sucks that this guy can’t experience this.” But it was a good reminder of why I need to keep doing my work. My hope one day is to provide more treatment options for men experiencing infertility.