Samarchith “Sam” Kurup grew up in India, and he’s always been aware of the impact of malaria.

In 2020 there were an estimated 241 million cases of malaria worldwide and an estimated 627,000 deaths, according to a recently released World Health Organization Fact Sheet. Eighty percent of the malaria-related deaths in Africa are children under the age of 5. The relapsing nature of the disease leads to educational and employment loss that has long-term economic impacts for both the individual as well as society.

“Malaria is huge global problem,” said Kurup, a member of UGA’s Center for Tropical and Emerging Global Diseases. “Almost half of the world’s population is currently at risk of contracting malaria.”

Kurup began his training in veterinary medicine in India, where he became hooked on parasitology, then continued his studies at UGA. While pursuing his Ph.D. he worked in Rick Tarleton’s lab, studying a parasitic disease that affects both animals and humans—his first introduction to human immunology. He continued his training in immunology as a postdoctoral researcher in John Harty’s lab at the University of Iowa.

Combining parasitology with immunology prepared him to tackle malaria.

Malaria is one of the most studied parasitic diseases, yet the Plasmodium parasite that causes it keeps evading attempts to treat the infection in humans. This is largely due to its complex life cycle and the ability of the parasite to evolve drug resistance. In addition to life stages that occur in the mosquito, which transmits the Plasmodium parasite to humans, there are two life stages in humans—a short phase of initial development in the liver, followed by an infection of the blood cells that causes clinical disease.

“A lot of research has been focused on the blood stage in humans, as this is when a person is symptomatic,” said Kurup, assistant professor of cellular biology in the Franklin College of Arts and Sciences. “But we now recognize that if we want to stop malaria, we need to stop it in its tracks in the liver before accessing the blood, and for that we need to understand the liver stage.”

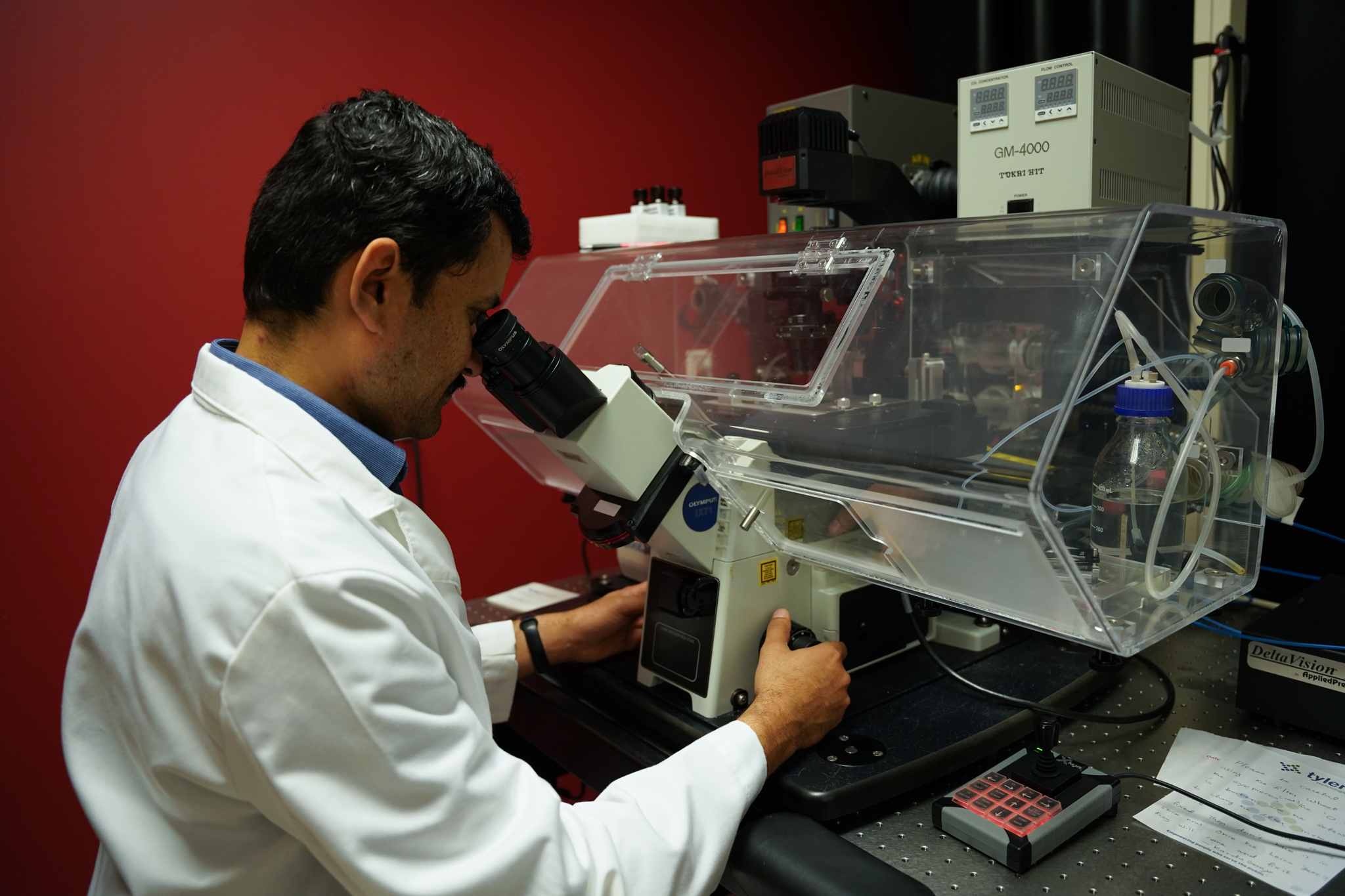

Kurup has been awarded a five-year National Institutes of Health grant to study the natural immune response to the Plasmodium parasite in liver cells.

“The liver stage is short and can be difficult to study in the laboratory,” he said. “There are also practical and ethical limitations to studying the liver stage of malaria in humans. We are hoping to tease apart the basic principles of immune responses during this stage using the mouse model.”

Kurup’s preliminary studies have shown that a group of signaling proteins called type 1 interferons play a role in the destruction of Plasmodium parasites in the liver. His newly funded project will fill a gap in the malaria knowledge base by using a combination of in vitro study and in vivo experiments to determine the molecular processes that eliminate Plasmodium parasites in liver cells. His group recently developed a transgenic parasite line that can be used to genetically alter its host cell.

“This strain is a game changer for our line of research because we can now determine how our liver cells would naturally eliminate the parasite, and maybe why it sometimes fails,” he said.

In a study recently published in Cell Reports, Kurup and colleagues used the genetically altered parasite to inhibit signaling by type 1 interferons and showed that this protein has a direct role in the control of malaria. Their study also revealed that other natural immune mechanisms may be active in controlling malaria in liver cells. The project funded by the new grant will delve further into these mechanisms.

“In addition to taking us a step closer to the control and possible eradication of malaria, this project will expand our knowledge so that we can better reduce the burdens of this illness in our society,” he said.

Kurup is hopeful that uncovering how the human immune system naturally fights malaria in the liver stage will lead to an effective malaria vaccine.

“I really believe that bringing together our knowledge in parasitology and approaches in immunology is key to uncovering new information on this elusive life stage in malaria,” he said. “There is no better place to do this, considering the intellectual and material resources we have at our disposal at UGA and the CTEGD.”