Imagine you could transport yourself from place to place with just a wink of the eye. What would you do first? Take today’s lunch break on the French Riviera? Or perhaps you thought of more practical things. Who’s going to regulate all this free movement, and what’s to keep thieves from entering people’s homes unchecked?

There is no right or wrong answer, but the question is not without purpose. Researchers use such imaginary scenarios to measure people’s creativity and problem-solving skills, and it is precisely the kind of question one might encounter while taking one of the Torrance Tests for Creative Thinking. Developed by the late E. Paul Torrance, professor and namesake of UGA’s Torrance Center for Creativity and Talent Development, the Torrance tests have become the international gold standard for evaluating creative potential.

“These tests are given to everyone from age 4 to 104,” said Sarah E. Sumners, interim director of the Torrance Center and research scientist at the UGA College of Education. “They tell us a great deal about people, and we can use the results to help them realize their own creative potential.”

Torrance developed a fascination with creativity while working briefly as a high school teacher, where he encountered “problem students” who, despite their off-beat ideas, went on to become successful in politics, business, science and other fields. What, he wondered, was it about these kids that made them different, and what could educators do to direct these creative impulses into something meaningful?

Over the course of his almost 50-year career, he worked to create and refine a test that could accurately evaluate creativity much like an IQ test aims to assess intelligence. During that time, he developed the conviction that creative thinking was not a gift but a skill, one that children and adults could cultivate for their own betterment and that of others.

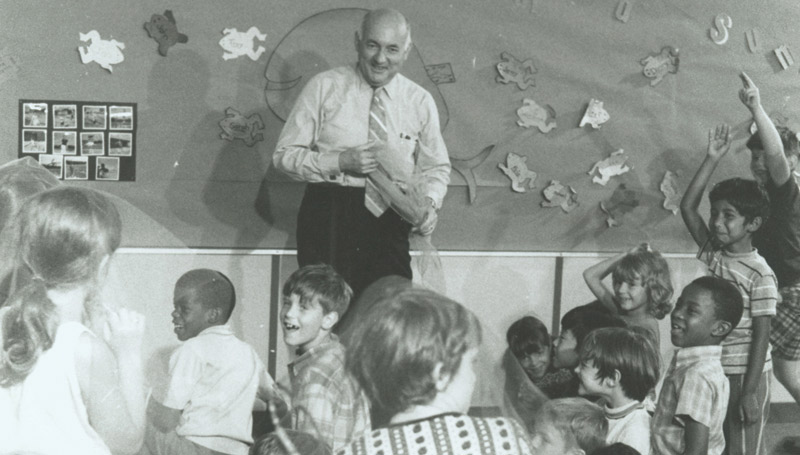

Torrance famously gave young students a stuffed animal purchased from a department store and asked them what they would do to improve it. This simple exercise gave him a glimpse into the children’s creative mind. As they turned the stuffed toy over in their hands and brainstormed ideas, Torrance noted the basic processes summoned to drive creative thought.

He pointed out that we tend, erroneously, to equate creativity with genius, extolling the fantastic achievements of a Mozart or da Vinci while all but ignoring the great potential of virtually everyone else. For him, creativity was inherent in all humans, arising from our basic need to relieve tension when something is sensed as missing or incomplete.

“Creativity is a process of becoming sensitive to problems, deficiencies, gaps in knowledge, missing elements, disharmonies, and so on; identifying the difficulty; searching for solutions; making guesses or formulating hypotheses about the deficiencies; testing and retesting these hypotheses and possibly modifying and retesting them; and finally communicating the results,” Torrance wrote in 1974.

Over the course of his career, he administered his tests to thousands of schoolchildren and he often followed them for several decades to see if those students deemed most creative went on to accomplish great things. While a person’s life experiences, work environment and no small measure of luck play important roles in his or her level of personal achievement, Torrance’s test results generally correlated with success.

While creating a battery of predictive tests was itself a major accomplishment, Torrance also wanted to find ways to help more children think creatively. His famous Incubation Model of Teaching married regular course content with challenges designed to arouse students’ curiosity, making them likelier to engage their creativity and explore a topic more deeply.

“Before creative thinking can occur, something has to be done to heighten anticipation and expectation and to prepare learners to see clear connections between what they are expected to learn and their future life (the next minute or hour, the next day, the next year, or 25 years from now),” Torrance wrote. “After this arousal, it is necessary to help students dig into the problem, acquire more information, encounter the unexpected, and continue deepening expectations.”

A prolific author and inspired advocate during his years at UGA, Torrance continued to publish and speak regularly following his retirement from the university in 1984. He passed away in 2003 at the age of 88, but he left behind an extraordinary legacy and a wealth of insights that remain vibrant through his many students and the Torrance Center, where faculty continue to help young and old alike find their creative potential.

“It’s hard to overstate how profound his impact was,” said Sumners. “Dr. Torrance was an amazing scholar, and we are proud to carry his work forward.”