The firefly is one of nature’s most extraordinary creatures. On warm summer evenings, as the sun dips below the horizon, these small winged beetles take to the air and transform the landscape into a silent symphony of blinking lights, a sight that has captivated human audiences for centuries.

Charming though it may be, the firefly’s light serves a serious purpose. It is a form of communication and the cornerstone of an elaborate courting ritual in which potential mates beckon to one another.

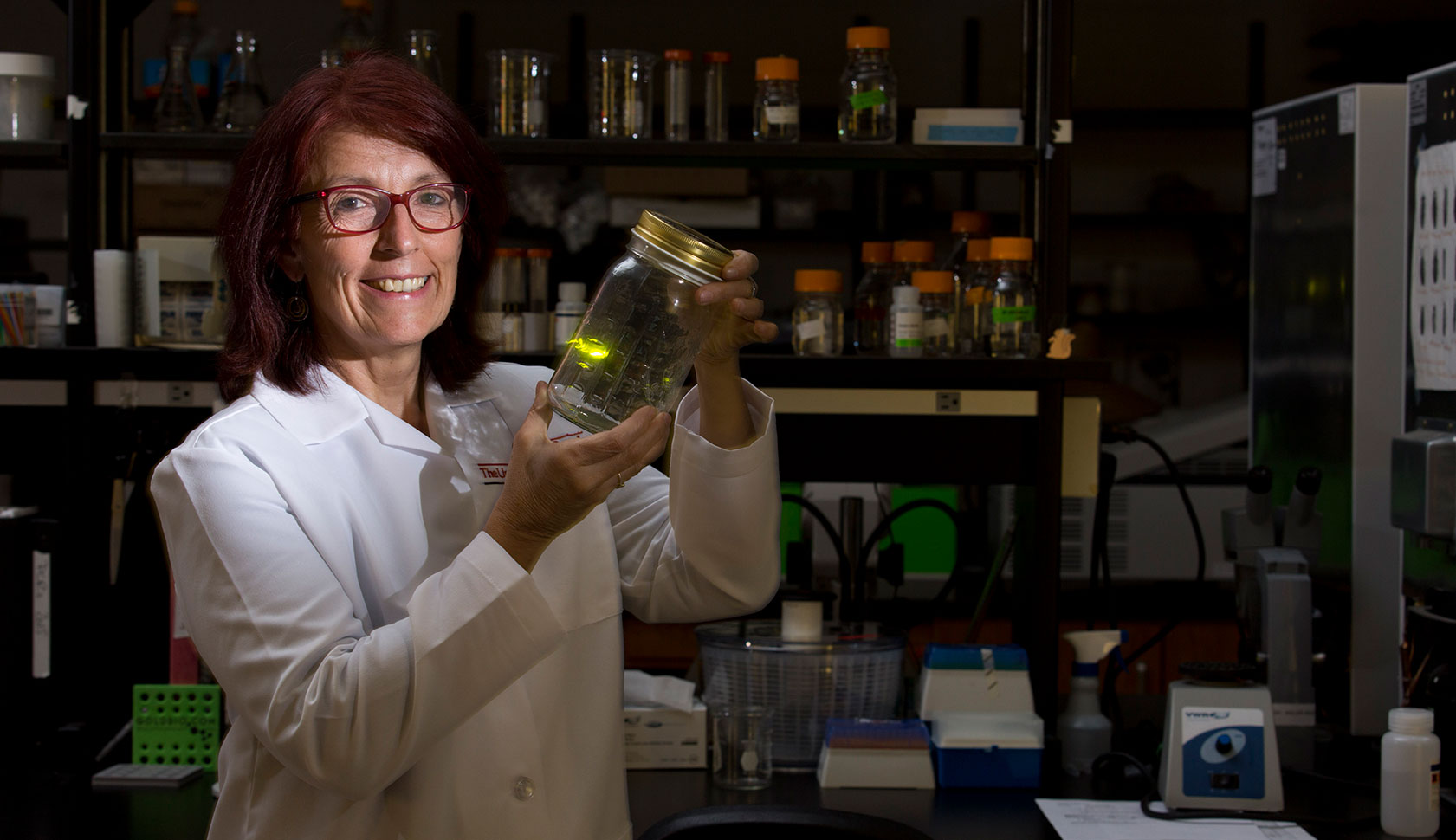

“Just as birds have their songs and colorful plumage, fireflies have their light, which they create by combining oxygen with a chemical called luciferin in their abdomens,” said Kathrin Stanger-Hall, an associate professor of plant biology at the University of Georgia who has spent several years studying the evolution of light signals in North American fireflies. “Their flashes are like a visual Morse code, and I want to understand how they use this code to communicate.”

Along with graduate student Sarah Sander, Stanger-Hall has made a number of discoveries about fireflies that help explain how their unique physical characteristics allow them to speak a language of light.

“The fundamental drive behind all this work is to better understand how animals communicate and what evolutionary forces made them favor one method over another,” Stanger-Hall said. “We’ve already learned so much from studying fireflies and their robust visual language.”

It may sound counterintuitive, but some fireflies do not produce light at all, preferring instead to communicate through pheromones detected through their antennae. Stanger-Hall conducted a study in which she compared the eyes of these lightless fireflies with those that do produce light.

What she found is that lighted species possess considerably larger eyes than their unlighted counterparts, and males generally possess larger eyes than females.

“If you look out in your yard in the evening, most of the fireflies you see in the air are males; females typically remain sedentary on pieces of vegetation,” Stanger-Hall said. “Lighted fireflies—the males in particular—need good eyesight to find the right mate because they may be sharing a habitat with 10 or more different species, each with their own unique flash patterns.”

The differences between these flashes are often subtle, but weekend naturalists can spot them with a little practice. Males belonging to the most common species in North America, for example, drop quickly in altitude and then climb sharply back up, forming the letter J as they flash. This unusual behavior has earned them the name “big dipper firefly.”

You may also have noticed that fireflies produce different hues of light, with some appearing yellow and others a deeper green color. Stanger-Hall and a team of UGA researchers, including Dave Hall, wanted to know the reasons for these differences, so they catalogued more than 7,500 individual firefly flashes from 24 species.

What they found is that the variations in color allow different firefly species to stand out in their respective environments, depending on what time of day they are most active.

“Fireflies that are active earlier in the evening will produce a yellower light to maximize contrast against green vegetation,” said Stanger-Hall. “In comparison, fireflies that are active in darker habitats will produce greener light, which is more visible at night.”

Stanger-Hall is also leading a study that will sequence the genes involved in light production to better understand how fireflies evolved their distinct flashes.