On a fine day at the University of Georgia Heritage Apple Orchard, you can see the fringing peaks of the Chattahoochee-Oconee National Forest rising around like a hedgerow, guarding against whatever forces might encroach.

When Stephen Mihm looks over the tops of the 275-odd dwarf apple trees that constitute the orchard, he sees more than a pretty view of the Appalachian foothills. He sees clear into Georgia’s past.

“These mountains were a center of commercial cultivation,” said Mihm, professor of history and associate dean in the Franklin College of Arts & Sciences, gesturing at the landscape. “We were growing these apples, many of them, that you see around you. Every tree you see is a variety of apple grown in Georgia at some point in the distant past, typically before 1920.

“The vast majority of them, you cannot find anywhere now in Georgia,” he continued. “Except on this hill.”

Planted three years ago during a global pandemic, the trees of the Heritage Apple Orchard are now producing fruit and well on their way to helping Georgia rediscover part of its agricultural legacy. Its 139 apple varieties represent a tantalizing pip of possibility: the revival of Southern apple culture, in all its former glory and complexity.

Lost Southern apples

Before it was reinvented as one of sport’s most iconic structures, the clubhouse at Augusta National was surrounded by acres and acres of fruit trees. Fruitland Nurseries, founded in the 1850s by Belgian immigrants, was one of the Southeast’s largest 19th century horticultural operations. Its 1860 catalog listed 900 varieties of apple tree, 300 varieties of peaches, and 1,300 pears.

After Fruitland closed in 1918, golfing legend Bobby Jones and his business partners purchased the property and turned it into the most famous golf course in the world, with the nursery’s former manor house now serving as clubhouse.

Fruitland may have been the pinnacle of Southern horticulture, but similar, smaller operations dotted the valleys of the Blue Ridge from Georgia to Virginia. Southern farmers both large and small served their local communities, growing a wide range of seasonal produce that included literally hundreds of apple varieties.

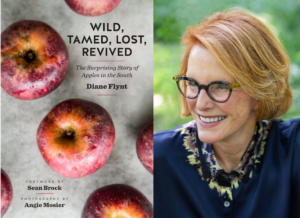

“In the South, we could eat apples, fresh apples without refrigeration [virtually year-round], from May through April [because of the different varieties],” said Diane Flynt, author of “Wild, Tamed, Lost, Revived: The Surprising Story of Apples in the South” and owner of Foggy Ridge Cider in Virginia. Flynt’s book traces the histories of Fruitland and Pomaria Nurseries of Columbia, South Carolina, another 19th century apple tree distributor whose success did not survive the Civil War.

“So, Early Strawberry and Carolina Red June, those come in late May, early June. And then Rall’s Janet and Winter Jon and Albermarle Pippin, those will keep,” Flynt said. “Arkansas Black—I ate an Arkansas Black in June that was in my refrigerator, which is about the temperature of a mountain coal cellar.”

As in so many industries, technology brought irrevocable change. Railroads began crisscrossing the country, hauling fresh apples to markets previously unreachable. Advances in storage technologies—such as refrigeration and controlled atmosphere (CA) storage, in which oxygen levels are kept low to slow ripening—meant that Carolina Red Junes and other early-season favorites could be kept fresh and enjoyed well into fall and winter.

Southern apples also fell victim to social and economic changes. Prohibition drove the cider and apple brandy producers underground. Growers discovered they could maximize revenue with denser orchards of fewer varieties, reducing costs by instituting uniform maintenance practices rather than catering to a wide range of particular needs.

By the early 20th century, the bulk of U.S. apple production had moved north to states like Washington and Michigan, and the industry’s focus on a small number of varieties led to a homogenization of consumer tastes. Southern growers tried to plant what consumers wanted—apples that grew well in northern climates—with limited success.

“When people try to grow a McIntosh or a Gala in Georgia,” Mihm said, “they’re trying to do something that is very, very difficult and not appropriate for the climate, for the pests, for all the other pressures that are here.”

By the 1920s, the Southern apple industry was a fraction of its former size. It would never recover.

Or would it?

From Monticello to Blairsville

The Heritage Apple Orchard can trace its origins to real estate transactions. Both Mihm and Josh Fuder, UGA Extension agent for Cherokee county, became interested in heirloom apples after they bought houses with apple trees already growing on the property. The history of those trees intrigued both enough for them to reach out individually to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Plant Genetics Resources Unit in New York, which connected them to each other, and the idea for the orchard was planted.

The pair worked to assemble DNA of heirloom varieties in the form of scion wood—cuttings from living trees—sourced from the USDA, from individual contacts still maintaining old trees, and from well-connected growers and nurseries in the Southeast.

Ray Covington, superintendent of the UGA Mountain Research & Education Center in Blairsville (a unit of the College of Agricultural & Environmental Sciences), offered a couple acres for the new orchard. The center was long acquainted with apple production, having grown stands of contemporary varieties for decades.

In 2020—just a week before COVID-19 shut the world down—Fuder led a workshop to graft the heirloom varieties to rootstock. They grew in pots for a year until February 2021, when a group of facemask-clad volunteers lent their labor to get the trees in the ground.

“These trees all have their own individual personalities,” Covington said. “There are 139 varieties on the property, and they’re all different. They bloom at different times; they have different growth habits; they’re ripening at different times.”

Several varieties have long and storied histories. Ben Davis was one of the most popular commercial apples of the 19th century. Thomas Jefferson grew Hewe’s Crab trees in his orchards at Monticello, as well as Newtown Pippins, which George Washington grew at Mount Vernon.

Because named apple varieties are always reproduced through grafting—apple trees grown from seed rarely produce the same kind of fruit as their parent trees—the pairs of Newtown Pippin and Hewe’s Crab growing at the Heritage Orchard are genetically identical to the trees described in Jefferson’s and Washington’s journals.

But the provenance of other rediscovered varieties is much less clear, and that’s why Mihm looks forward to working with plant scientists to do genetic testing on the trees, both to discover commonalities with other known varieties and to isolate genes associated with beneficial traits such as heat tolerance and disease resistance.

“When you look at all these varieties, there are a lot of mysteries here. We actually don’t know how they’re all connected, but there’s a very good chance that many of these have common ancestors,” Mihm said. “Up north, for example, genetic testing has shown that many trees historically found in New England are not purely of English origin but are actually French.

“So, sacre bleu, we have this French foundation to a lot of things we identify as American. It may be quite different in the South. There’s even a chance you could find Spanish apples in our particular mix, but we won’t know until we start testing.”

Even the precision of modern genetics, however, may not solve all the mysteries.

“The challenge in a lot of these lost varieties is, yes, we have DNA testing now, but a lot of the Southern apples are not in the backlog of genetic data,” Fuder said. “So even if we sent our Family variety for testing, that may be the only one they’ve ever tested and it would come back as unknown, or sharing the same parents or grandparents as another variety. But they wouldn’t be able to tell us, ‘Yeah, you’ve got Family there.’”

Learn about lost (and found) Southern apples

Below are just a few of the 139 heirloom apple varieties growing at UGA’s Heritage Apple Orchard.

Source: Pomiferous.com

Growing interest & industry

Drew Fitchette has a rule of thumb for cider apples: “The uglier the apple, the better the cider.”

Fitchette is an aspiring cidermaker from Atlanta who heard about the Heritage Orchard, and on a fine day in early September, made the trek up to Blairsville to see the apples for himself.

“Only bold flavors survive the fermentation process,” he said. “I’m interested in finding Southern apples with the sort of tannins and acidity that would make it through that process. Most of these old apples have characteristics that have been bred out of more popular varieties.”

Fitchette is not the only one asking about UGA’s apples.

“There was an enormous amount of media coverage when the orchard was first planted,” Mihm said. “Now we’re starting to see these inquiries because, especially in Atlanta where there are cideries popping up, the need and the desire for apples that are out of the ordinary is growing quite quickly. Many of these are microbreweries that are starting to branch out into cider.”

Rare and unique flavor profiles are important for cider, but even more vital are essential characteristic like susceptibility to disease and an ability to handle hot, humid Southern summers.

Three years into the ground, the trees are proving history correct. The Heritage Orchard is planted next to several thick rows of Golden Delicious, which are suffering from Glomerella leaf spot, a fungal disease common to apple trees, and being treated heavily with pesticides and other chemicals. The heirloom cousins growing beside them show no sign of sickness.

“We are starting to observe some standouts, some truly disease-resistant varieties,” said Fuder, who over the summer led a team of Extension agents to inspect and grade the trees. “We just went through tree by tree and gave them scores. Are we seeing fire blight? If so, how bad is it, one to five? Are we seeing Glomerella, bitter rot, all of our primary apple diseases?

“After all,” he said, “what good is a nice tasty apple if we can’t grow it here?”

The orchard keepers have kept in touch with larger apple growers from Ellijay and Blue Ridge, who certainly will play a role in any revival of Georgia apple culture. Even if a small cidermaker like Fitchette wanted to work with UGA’s apples, Mihm said, they likely would contract with a commercial orchard to devote a section of its acreage to the heirloom varieties, which would be trimmed for scion wood, grafted, and planted in their new home. The apples, of course, would come a few years later.

“Commercial growers want to see the fruit—they want to see a bushel of apples in front of them and taste them. We’re still in the early stages. This beautiful tree right here,” Covington said, gesturing to a King David, “is on its third year, maybe fourth year. It’s nice and tall, but it’s still not a full-producing tree.”

That won’t be the case for much longer. The Heritage Apple Orchard soon will boast mature trees whose branches will be laden from late May to November with apple varieties that have not seen the Georgia sun since before the first World War. Already, Flynt groups UGA’s orchard with the Horne Creek Farm’s Southern Heritage Apple Orchard in North Carolina, the largest heirloom orchard in the country, whose 850 trees include more than three times as many varieties as UGA’s farm.

For those who brought the Heritage Orchard to life, the future is sweet indeed.

“If we’d scheduled our grafting workshop just two weeks later in 2020, the orchard would not have happened [due to the COVID-19 lockdown],” Mihm said. “There were just many, many obstacles. To see an orchard—a very large orchard, at that—happily growing despite all the trials and tribulations, and now coming into its own to achieve the ends we hoped, is extremely rewarding.”