The doctor is In?

Over the past decade, Georgia’s rural communities have seen eight hospitals close and countless primary care clinics, specialist offices and pharmacies shut their doors. Finding primary care providers close to home, let alone specialists, has become increasingly difficult.

Zhang has been researching how access to telehealth programs can help rural hospitals provide acute care to stroke patients. In a study for Health Affairs, she found a correlation between the expansion of telestroke services nationwide with improved quality of care and fewer deaths due to stroke in very rural communities.

Her Georgia-based work has pointed to the positive trend of higher survival rates of stroke patients among facilities that introduced telestroke interventions.

More recently, Zhang has been working to characterize provider shortage trends in all Georgia counties.

Analyzing the density of primary care physicians, nurse practitioners and physician assistants across all Georgia counties from 2009 to 2017, “we found that although the number of primary care providers increased in both rural and urban counties during this period, the increase was more pronounced in urban than in rural counties,” she said.

But closing rural-urban gaps in access to primary care providers may require increasingly intensive efforts targeting rural areas, said Zhang, assistant professor of health policy and management. Currently, some of Georgia’s medical schools are offering tuition waivers to students who commit to a rural-based residency after school.

“You have to look at the full picture of why doctors are leaving,” she said. Is it because rural doctors have a higher number of uninsured patients, so it’s hard to stay in business? Or because there are fewer economic or education opportunities for their families?

“We need to better understand all of these things,” said Zhang. “It’s going to take more than tuition waivers to keep doctors in these communities.”

The heart of it

Heart disease is the leading cause of death in Georgia, and again, it’s Georgia’s rural areas that are the most vulnerable.

“Cardiovascular disease risk among men is two times higher in rural than in urban regions, and much of this disparity can be explained by lack of access to preventive services and lower socioeconomic status,” said Zhang.

How living in a rural community contributes to lifestyle factors that can lead to cardiovascular disease is another key area of research for the team.

Zhang has been leading the effort to develop and update an agent-based simulation model—an approach that was first developed to assess food environments in urban settings—to inform local policymaking around key lifestyle factors like diet and smoking.

The model takes into account the many factors that influence a person’s behavior, including demographic information, the local food environment and even health beliefs.

“A model can help us understand the whole system, to understand the interplay of complex factors,” said Zhang.

Zhang and Thapa published a study in 2019 showing that the agent-based model could be successfully translated to rural communities.

They ran a simulation using data collected on the food environment of a small town in Texas and found that reducing the distance to a source of fresh fruits and vegetables, like a farm stand, would increase consumption by 25%.

Their current project involves simulating and testing local policies that could change the community environment to reduce cardiovascular disease in Georgia’s hardest-hit counties, including policies on nutrition, smoking, lifestyle interventions and telehealth expansion.

Understanding what works where

Beyond simulation modeling, Thapa and Zhang have used large, longitudinal datasets to evaluate nutrition policies implemented at the state level—including the Strong4Life school nutrition program, which aims to “nudge” students to choose healthier foods at lunchtime; and Georgia SHAPE, a statewide childhood obesity initiative that called on schools to provide more opportunities for physical activity, whether that’s through recess or movement integrated into the classroom.

While these studies pointed to some positive effects, they also found disparities in policy implementation based on geography and socioeconomic status of the schools.

“Each school serves a unique neighborhood with varying access to healthy food options or opportunities for physical activity, such as sidewalks to walk on or parks to take kids to play. These factors play a role in physical activity and fitness outcomes of children,” Thapa said.

Thapa and an interdisciplinary team of UGA researchers are currently mapping each school and its surrounding environment to explore how the location of the school may have contributed to SHAPE’s success.

The findings from this study could further inform and improve the statewide obesity policy by identifying needs and avenues for localized efforts at schools within neighborhoods that discourage healthy eating and physical activity, said Thapa.

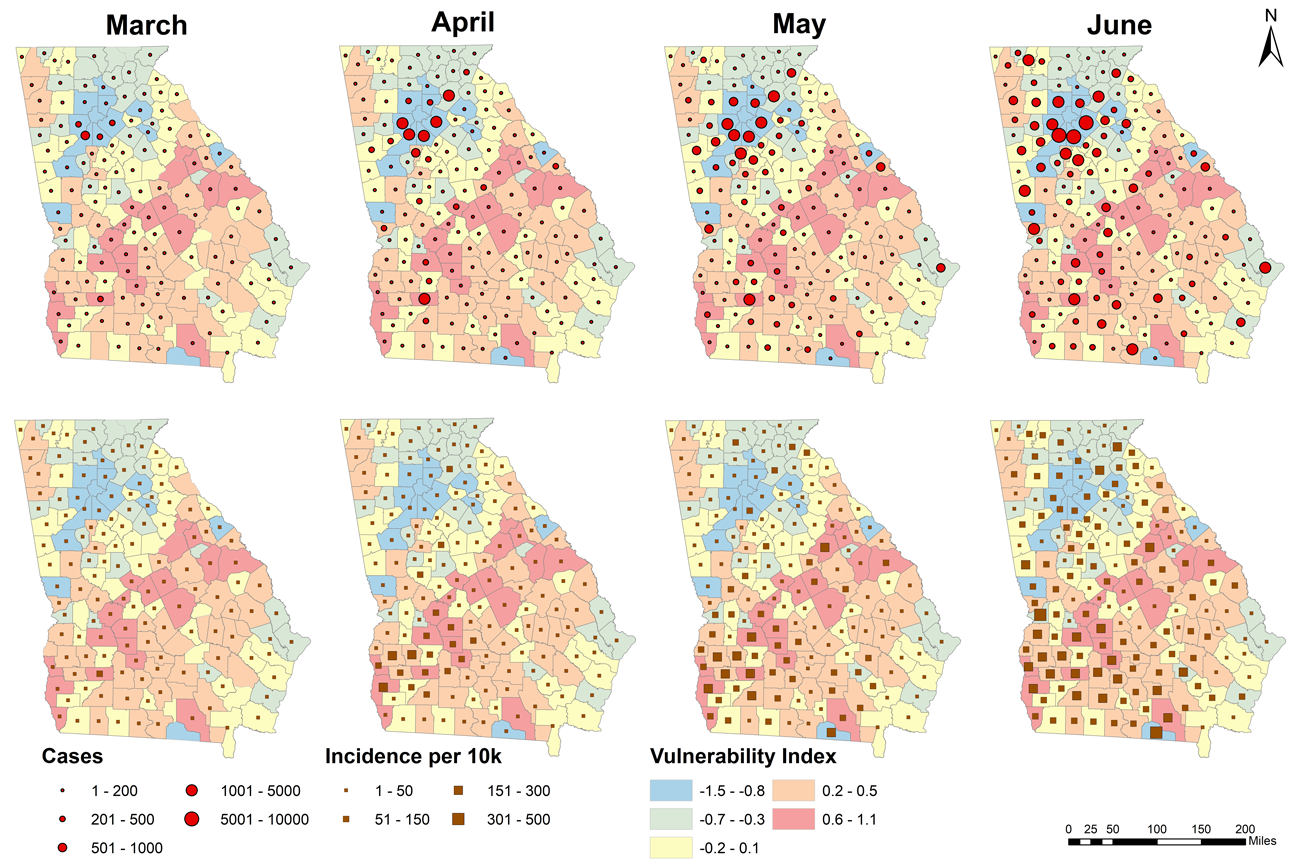

When the coronavirus pandemic first made its way to Georgia in March 2020, the majority of cases initially were found throughout the state’s rural and more vulnerable communities, including the city of Moultrie. (Photo by Winnie Gier)

Entrenched disparities

The main thread running through Thapa and Zhang’s portfolio of research is the role of social vulnerability on health, and there is no ignoring the critical part racial and ethnic disparities play in the health outcomes we see in Georgia, they said.

“Our research paints a picture of ongoing disparities in the state of Georgia,” said Zhang.

Their research is revealing not only the impact of social determinants, but also issues related to policy implementation, participant voices on policy interventions, and policy reach to promote healthy lifestyle behaviors. Heart disease, stroke, and obesity disproportionately impact Georgia’s black communities, and the impact of COVID-19 has laid bare the systemic inequities that contribute to these issues, according to the researchers.

“Racial and ethnic health disparities existed long before the COVID-19 outbreak in the U.S. and in Georgia,” Zhang said, “but the excess burden of COVID-19 among African American individuals may be mitigated by identifying, targeting and prioritizing modifiable factors.”

As their COVID-19 mapping work continues, Thapa is sharing the team’s findings widely with state and county leaders, stressing the cumulative vulnerability tied to race, poverty and rural status.

“All our findings boil down to informing resource allocation to mend existing inequalities—and to the fact that health is a social good,” Thapa said.

This story first appeared in the College of Public Health’s 2020 Annual Magazine and is reprinted with permission.