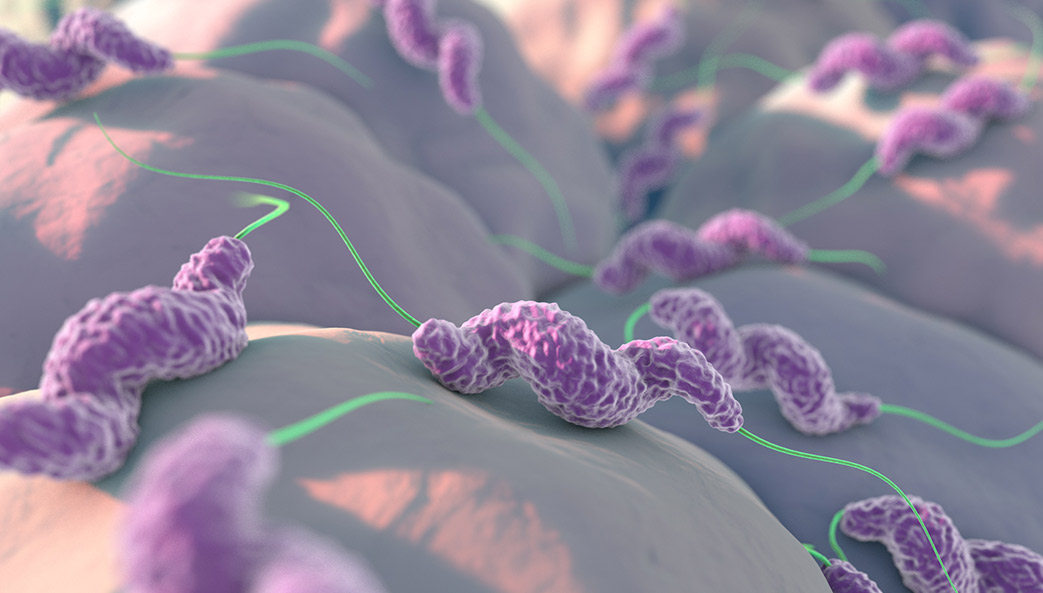

A common gut bacterium’s reliance on hydrogen presents a pathway to potential new treatment for gastric cancers, which kill more than 700,000 people per year, according to a study led by UGA researchers.

The study shows how the bacterium Helicobacter pylori uses hydrogen as an energy source to inject a toxin known as cytotoxin-associated gene A, or CagA, into cells, resulting in gastric cancer.

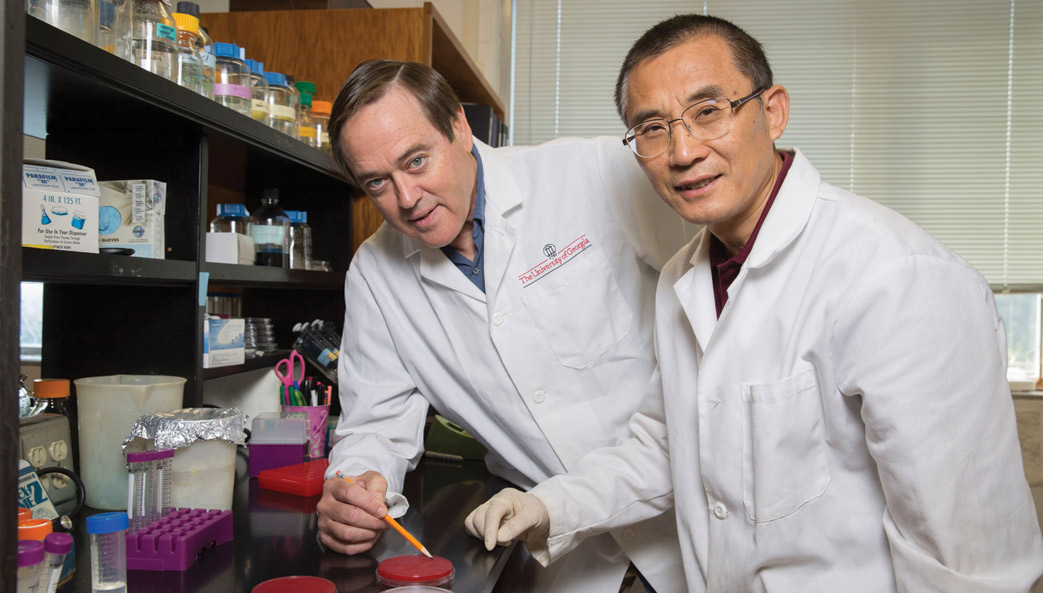

“These findings have potentially significant clinical implications. If we can alter the bacterial makeup of a person’s gut, we can put bacteria in there that don’t produce hydrogen or put in an extra dose of harmless bacteria that use hydrogen,” said Robert Maier, Georgia Research Alliance Ramsey Eminent Scholar of Microbial Physiology in the Franklin College of Arts and Sciences. “If we can do that, there will be less hydrogen for H. pylori to use, which will essentially starve this bacteria out and result in less cancer.”

A 2002 study led by Maier showed that the presence of hydrogen in the gastric chamber was important for bacterial growth. It wasn’t until the current study, however, that researchers learned of the cancer connection: The bacterium harnesses the energy from hydrogen gas, via the enzyme hydrogenase, to disrupt host cell function and cause cancer.

“We didn’t realize that pathogens like H. pylori could have access to hydrogen inside an animal in a way that enables the bacterium to inject this toxin into a host cell and damage it,” Maier said.

The study was published by the American Society for Microbiology journal mBio.