The ethics of returning

Beyond travel restrictions, there are a host of other issues researchers should consider before returning to fieldwork, according to Hecht.

“We should question not just broader research agendas, but really think critically about the ethical quandaries that come along with doing anything community-related or engaging people who might be marginalized and therefore vulnerable.”

This issue is particularly acute for associate professors Julie Velásquez Runk and Nicole Gottdenker, who are part of a multimember NSF-funded project to study zoonotic disease transmission in Panama.

While the project remains on hold, there are still questions: When should they return? How will team members strike a balance between community safety and research productivity? Runk and Gottdenker are mindful of the history of devastating population losses after European-introduced diseases in the colonial era, as well as the current spike in COVID-19 cases in the United States.

“I don’t want to be there at all if there is the potential of spreading it unintentionally,” said Runk, an interdisciplinary environmental scientist and associate professor in the department of anthropology.

“We really don’t want to invade communities when we shouldn’t be there,” said Gottdenker, associate professor of veterinary pathology. “We really want to be safe.”

Graduate student Vanessa Raditz canceled research plans in Puerto Rico after an influx of COVID-19 cases were linked to spring break tourism.

Raditz, an environmental health researcher who studies LGBTQ+ vulnerability to climate change, said they were particularly concerned about the potential for additional strain on a health care system still dealing with the aftereffects of Hurricane Maria. “It’s immoral and unethical.”

COVID-19 constraints spur creative approaches

Embracing the challenge of forgoing fieldwork has led to new innovations and insights. As someone who uses collaborative documentary film in their research, Raditz has had to be particularly creative.

“I have really had to lean into the collaborative aspect,” they said. “I’m doing a lot more with the folks that are on the ground for them to be documenting things, collecting footage and sending it to me, and having conversations about what they are sending to me.”

While many assume effective collaboration requires being in person, Raditz reports the opposite: “It has gotten people a lot more engaged.”

Raditz also adds this experience has made them think more about the relationship between frequent travel and carbon emissions. “The creative constraint that this has created is a good reminder that we do have other ways of doing our research that don’t involve us flying all over the place.”

The push to complete research is particularly important for graduate students, who often find themselves with limited funding and on a specific timeline to graduate, according to Gottdenker.

“What I worry about is graduate students,” she said, “because they might need an extra year of study.

Runk agreed.

“Not having in-person research is making things take much longer.”

Aware of these constraints, and the historical emphasis on doing anthropological fieldwork in foreign locations, she spoke to anthropology students last spring about ways to continue research amid local and international restrictions. These included using public data sources for analysis and using video and other media to create “multimodal” publications.

Pivoting leads to new insights

Many researchers form direct, sustained and close relationships in the communities where they work and have felt compelled to use their past research experiences to respond to COVID-19. This summer, Runk, who has worked with indigenous communities in Panama for over 20 years, used platforms like WhatsApp to bring together doctoral students and Panamanian collaborators to create COVID-19 health messaging for distribution among indigenous communities.

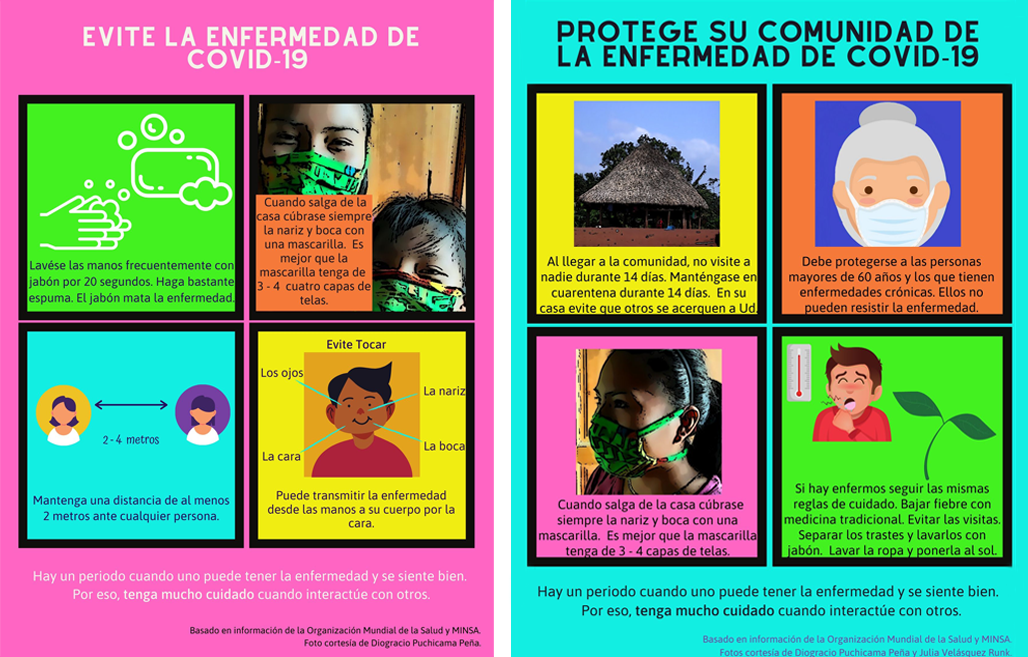

Given the remoteness of indigenous communities, the team created graphic posters that could be easily distributed and viewed on cell phones. The posters communicated how to protect the community and avoid the spread of COVID-19 in ways that resonated with those specific communities. “We very intentionally worked with vocabulary and images that reinforced indigenous ideas,” Runk said.

Early into the project, Runk and her collaborators realized there was a problem with most stock art and photographic resources. They are often biased in a way that prevents effective communication with indigenous communities. Given the importance of clear messaging during health crises, this insight has generated discussion about the need for future research on developing culturally inclusive resources for stock art and photography.

Hecht, unable to leave Bhutan since March, has watched the COVID-19 pandemic unfold within the country’s unique cultural and political context. The Bhutanese government immediately took steps to support its citizens both at home and abroad. Residents made offerings to their local deities, promoted healing mantras, and distributed laminated cards of Sangay Menlha (Medicine Buddha) within their wider community. Authorities have worked to bridge global health directives with culturally appropriate and reassuring messaging.

For Hecht, one experience in particular stands out.

Last March, shortly after national messages announcing the first case of COVID-19 in the country were sent, many residents received the afternoon off work so they could witness the head of the monastic body, known as the Je Khenpo, initiate the Sangay Menlha over television and social media platforms to assist in the healing of illnesses of both body and mind. Watching from home as hundreds of thousands of residents received the blessings of the Je Khenpo, Hecht felt reassured.

“I felt it—in the community watching it with my friends and colleagues in their homes—this tremendous wave of peace and being well taken care of.”