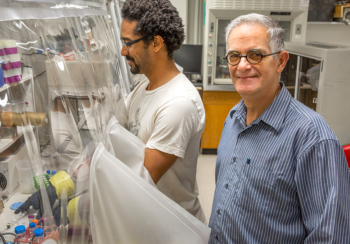

When small hydroelectric projects began dotting the rivers of the Western Ghats, a strip of mountains that runs parallel to the west coast of Peninsular India, Odum School of Ecology and Integrative Conservation (ICON) graduate student Shishir Rao pivoted from a career in IT to study their impact.

He wanted to know how these impoundments affect fish variety and abundance, and alter the river’s habitat and water chemistry.

Rao, a 2023 recipient of a John Spencer Research Grant, always had an avid interest in ecology and conservation, feeling what he describes as both curiosity and concern for the natural world. He credits that curiosity, in part, to an upbringing playing in the river outside his grandparents’ home in coastal Karnataka.

“The first thing I would do is run to the river. I wanted to catch fish. The river has always held a very strong connection for me,” he said. “The concern part came later on, when I was volunteering for different NGOs.”

One of his earliest volunteering experiences involved assisting the Karnataka Forest Department with their crowd control and awareness activities focused on pilgrims and tourists visiting temples in the remote forests of the Western Ghats.

But throughout his undergraduate degree in engineering and in his early career, he had no idea the discipline of freshwater ecology was an option. It’s now a steadily growing field in India.

“Ever since I understood that this is a legitimate career, I started preparing for it,” Rao said.

That was when he finally quit his job and joined a research project looking at the effects of small hydropower dams on fish, and the perceptions of local communities toward these dams. Rao spoke the local language, and the team brought him on board to conduct the interviews. Once on the project, he became increasingly interested in studying tropical river ecosystems with a conservation focus.

“From that point onward, I didn’t look back,” he said.

The logical next step was a master’s degree, and he landed a spot with the M.S. Program in Wildlife Biology and Conservation at the National Centre for Biological Sciences (NCBS), Tata Institute of Fundamental Research. Every two years, the program accepts only 15 students in all of India.

While there, he became interested in understanding how a river’s hydrology and ecology are linked. For his master’s thesis, he continued his research in the Western Ghats, studying how freshwater biodiversity responds to flow alteration by small hydropower projects. It was vital work—the rivers of the Western Ghats are a hotspot for freshwater fish biodiversity. Of 288 recorded species, 118 are endemic to the region, 54 are endangered and 24 species are critically endangered.

“I wanted to see how the flow is different in different sections of the river,” Rao said. “Then we could really explain why the fish community looks a certain way in these different stretches of the river.”

In sections of river that experienced sustained, fluctuating flows, he found very few fish. It’s a novel environment where fish might find mobility difficult, or where eggs may be washed away, he explained. In the stretches where the flow was reduced, he found more hardy, non-endemic species of fish compared to sensitive and endemic species, highlighting how fish communities respond to altered flow conditions.

Zooming out: Human-ecosystem interactions and large dams

His flow ecology research is work he’s built on during his Ph.D. studies here at UGA in the Aquatic Ecology and Conservation Lab, advised by Seth Wenger, associate professor and director of science at the River Basin Center. But the scale of research is much larger and includes a stronger sociological component.

Rao wants to know how dams alter sediment transport in addition to flow, how flow alteration affects estuarine systems—because estuaries rely on the river’s ability to transport water and sediments naturally—and to understand how river-dependent people adapt to ecological changes caused by flow alteration.

“I wanted to see how the flow is different in different sections of the river,” Rao said. “Then we could really explain why the fish community looks a certain way in these different stretches of the river.”

In sections of river that experienced sustained, fluctuating flows, he found very few fish. It’s a novel environment where fish might find mobility difficult, or where eggs may be washed away, he explained. In the stretches where the flow was reduced, he found more hardy, non-endemic species of fish compared to sensitive and endemic species, highlighting how fish communities respond to altered flow conditions.

Beyond a Ph.D.

Outside of academia, Rao is an avid badminton player and follows professional badminton passionately. He also enjoys cooking. Though he’d been a vegetarian for years, he just recently began eating fish—he joked that he’s eating his study subjects.

After his Ph.D., Rao hopes to return to his work with conservation NGOs for a while, doing applied and interdisciplinary research on river ecosystems.

Before that, though, Rao faces a difficult season of life. Graduate studies are notoriously grueling, but students who study in the U.S. and then conduct field work internationally face unique challenges, including navigating the time change and a sometimes-suspicious public reception to field work.

“It’s a lot of mixed emotions and it’s really overwhelming. It feels like you’re alone in this journey,” Rao said.

He feels lucky to have understanding advisors. And Odum, ICON and the River Basin Center have been a natural fit for his research interests.

In fact, someday, he’d love to help get an interdisciplinary center on its feet in India, continuing his work at the nexus of freshwater ecology, social sciences and policy.

“I’ve always said this—we need a River Basin Center in India as well, because there are very few organizations that dedicatedly work on freshwater ecosystems,” Rao said. “I am super inspired by what the River Basin Center does.”

This story first appeared on the River Basin Center website and its republished with permission.