How rare is Earth? And is there another one?

“Good science begins with good questions,” said Roger Hunter, NASA Small Spacecraft Technology program manager and associate director of the NASA Ames Research Center.

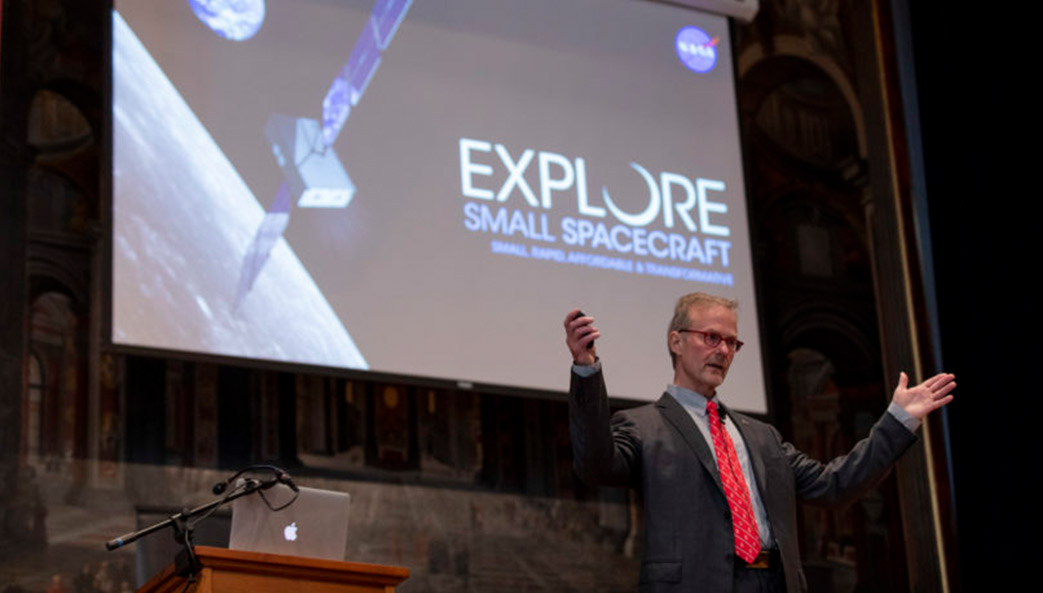

Hunter spoke about how his work helps answer those questions during the 2019 Charter Lecture, “NASA’s Kepler Mission and Small Spacecraft Technologies: Today and Beyond,” held March 20 at the Chapel.

“For NASA, there are three fundamental questions: Are we alone? How did we get here? And how does the universe work?” said Hunter, who received his Bachelor of Science in mathematics from UGA in 1978.

Hunter and his team seek answers by identifying and supporting the development of new subsystem technologies to expand the capabilities of small spacecrafts for NASA. One such task was serving as program manager for NASA’s Kepler Mission, which sought to discover and locate Earth-like planets in habitable zones (where the temperature is right for water to pool on the surface) in the Milky Way galaxy.

Kepler completed two missions. After four years, two gyroscopes on the spacecraft failed, but NASA engineers were able to come with a way to still point the spacecraft accurately enough to find planets by using the remaining gyroscopes and the solar wind.

“They kept the mission alive, which allowed us to do even more interesting astrophysics and detect more planets,” he said.

According to Hunter, during its more than nine years in space, Kepler provided a definitive answer to whether or not there are more habitable planets like Earth.

“The results have been astonishing,” he said. “We found planets galore.”

Thousands of planets and stars

The spacecraft was 94 million miles away. It confirmed 2,662 planets and observed 530,506 stars. According to Hunter, one out of every five stars has an Earth-size habitable zone planet—and that’s the conservative estimate.

“So, Captain Kirk is going to have a lot of M-Class planets to go explore now because of Kepler,” he said with a laugh.

NASA’s work also can help scientists and researchers understand what’s happening on this planet. For example, satellites were used to take images of the Carr and Camp fires in California last year.

Now, NASA is working on the next generation of space telescopes after Hubble. In order to use one of the future telescopes to look at a planet that is 50 light years away and take images of it, we have to think bigger, Hunter said. Some of the telescopes can have a 40- to 50-meter aperture.

In other ways, the future is also smaller. Hunter mentors students in the UGA Small Satellite Research Laboratory who are preparing to launch satellites the size of a tissue box with NASA and the Air Force Research Laboratory.

Before looking to the future, Hunter also wants these students to understand the past. He spoke about the Apollo 8 mission in 1968, where Frank Borman, Jim Lovell and Bill Anders became the first humans to reach and orbit the moon. They had a lasting impact on him, saying that in all of the bad that happened that year, those astronauts stood out as something good.

“We had something we could aspire to,” he said. “Now, we need you more than ever. You’re part of the solution. We want you to realize your dreams, and we want you to make this world a better place. There’s no telling how far your dreams might take you.”

Hunter reminded the audience that the future for NASA looks a little different than it did in 1968. For example, there are now 80 spacefaring nations. The NASA budget is expected to go from almost $350 billion in 2018 (not counting classified budgets) to $2.7 trillion in the next decades.

More missions to come

“I want to offer you a challenge,” Hunter said to the students in the audience. “Kepler’s orbit takes it around the sun at a slightly slower pace than Earth. On Sept. 25, 2060, Earth is going to go right by Kepler. You need to go up and get it. Bring it back, and put it in a museum, because it is, like many of our other missions, a tribute to human ingenuity.”

The UGA Small Satellite Research Laboratory isn’t the university’s only connection to the stars above. In 2013, Hunter helped make UGA the world’s first university to have a planetary system named after it—UGA-1785.

“If you [students in the UGA Small Satellite Research Laboratory] are able to make these missions work, I’m sure there will be following missions to come behind them,” Hunter said. “There will be other Space Dawgs to follow in your footsteps.”

The Charter Lecture is sponsored by the Office of the Senior Vice President for Academic Affairs and Provost and is part of the university’s Signature Lecture Series.