Every morning, Nsangi Racheal Sebuufu and her children wake before dawn.

The kids go to the well to fetch water. Then they help her milk the cows. She makes breakfast, does household chores and sees the children off to school before making her way to the fields where she grows crops and raises dairy cattle.

“The beauty with dairy is the daily income,” she says in Luganda, the language of Uganda’s Baganda people. “The difficulty is selling our evening milk.”

Where Sebuufu lives in rural Uganda, electricity is scarce. That means much of the milk collected in the evenings (about half of all milk produced in Uganda during the rainy season) is wasted because there’s no way to keep it cool overnight. Some women buy ice to pack around containers of milk, but it’s an ineffective and often costly solution.

And for African women, who comprise much of the poor farming workforce in the country, that’s money they can’t afford to lose.

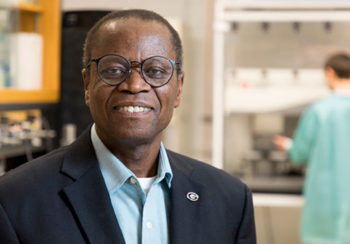

Without electricity, there’s no way to keep milk cool in rural Africa. Engineering professor William Kisaalita is changing that. (Footage courtesy of Gabriel Mundaka)

“If you look at sub-Saharan Africa, you’re going to see that women are the poorest population and that they are the ones maintaining the farms,” says William Kisaalita, a professor of engineering at the University of Georgia. “If we can double their income, the impact is huge. People say, ‘They’re only earning $5, and you’re making it only $10.’ But if you were making $20 and it got doubled to $40, wouldn’t you dance on top of a table? You would because it’s a huge difference.”

A native Ugandan himself, Kisaalita was determined to find a way to maximize small farms’ dairy profits. Using his background in mechanical and chemical engineering, Kisaalita and his team developed a cooling device that doesn’t require in-home electricity.

The Evakuula has two components: The first heat-treats the pooled milk to kill much of the bacteria in it, and then the second rapidly cools the milk to a temperature that prevents spoilage.

Known as thermisation, the heating process is similar to what is done in larger dairies to store milk before processing, but it’s shrunk down so that local farmers can use the technology on their own small farms. Instead of electricity, the Evakuula process uses heat derived from a plentiful biofuel: cow manure. As the manure is piled and begins to decompose, it emits methane, a greenhouse gas that traps more heat in the atmosphere than carbon dioxide. Kisaalita’s machine captures that gas and uses it to heat the milk. (That biogas can also serve as fuel for other uses, such as cooking and lighting.)

“This is the land that gave me birth. This is my opportunity to give something back.”

– William Kisaalita, Georgia Athletic Association Distinguished Professor, College of Engineering

Immediately after heating, the milk is transferred to the cooler, which uses evaporative cooling to chill the milk to about 10 degrees below room temperature. The mechanics behind the process are relatively simple.

“You know how when you are in a swimming pool and you jump out on a windy day, you feel very, very cold? The reason you feel cold is because the water drops on your body are evaporating and taking some of your body heat with them.”

Evakuula’s cooling process works the same way. The milk is placed in a cooler with an attached fan that hastens the evaporation of water droplets off the milk canister.

The milk container doesn’t take up the entire Evakuula cooling canister, so farmers like Sebuufu are also able to use it to cool and preserve other food for their families.

“With the Evakuula, evening milk is sold, and I have more income. Life is better,” she says.

As for Kisaalita, he’s not satisfied stopping with milk. He and his team of researchers are now using the Evakuula technology to create a cooling container for eggs.

“This is the land that gave me birth. This is my opportunity to give something back.”

About the Researcher

William Kisaalita

Georgia Athletic Association Distinguished Professor

School of Chemical, Materials and Biomedical Engineering

College of Engineering