In a recent paper, UGA researchers describe new tools they have developed in the fight against cryptosporidium, a microscopic parasite that causes the disease known as cryptosporidiosis—or “crypto,” as researchers often call it.

Crypto is most commonly spread through tainted drinking water. The parasite is especially problematic in regions with limited resources, where, as recent global studies have shown, crypto is one of the major causes of life-threatening diarrhea in infants and toddlers. But crypto can be a problem in developed nations as well. In 1993, more than 400,000 people living in the Milwaukee area were infected with the parasite when one of the city’s water-treatment systems malfunctioned.

“One of the biggest obstacles with crypto is that it is very difficult to study in the lab, which makes scientists and funders shy away from studying the parasite,” said Boris Striepen, coauthor of the UGA researchers’ paper and Distinguished Research Professor of Cellular Biology in the Franklin College of Arts and Sciences. “We think that the techniques reported in this paper will open the doors for discovery in crypto research, which in turn will lead to new and urgently needed therapeutics.”

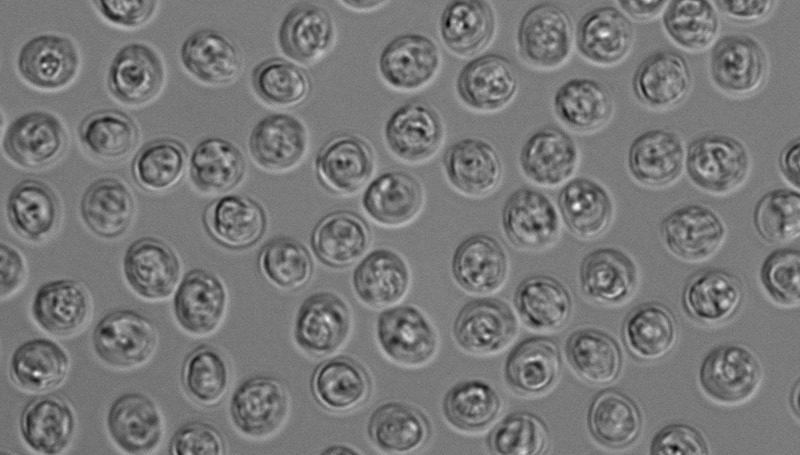

One of the authors’ techniques involves manipulation of the parasite so that it emits light, making it much easier to detect and follow. Previously, researchers would have to examine samples under a microscope and count crypto spores one by one, a time-consuming and unreliable process. Now, simply by measuring light intensity, researchers may test thousands of drug candidates at once to see if any have the ability to inhibit crypto growth.

“Enormous chemical libraries are available now, and some of these chemicals may work as treatments for crypto,” said Striepen, who is also a member of UGA’s Center for Tropical and Emerging Global Diseases. “This technology will help us find them much more rapidly.”