If you were to visit Charleston, S.C., in the early 18th century, you would instantly be greeted with the smells and sounds of cattle.

When British colonists first visited the area., in 1670, they found coastal marshes, open savannahs, thick pine forests, canebrakes, and a warm, humid climate. They brought with them various European crops and livestock, including cattle, to settle the land.

Cattle had been introduced by Spanish settlers a century earlier. Their offspring were largely free-ranging animals; some were feral. Some did a great deal of damage to the crops of Indigenous populations.

Colonists saw the area as a perfect location for raising cattle year-round and quickly become major suppliers of beef, hides, and tallow to Europe and the West Indies.

As the centuries passed, the importance of this early cattle industry was overlooked and Charleston largely became known as a major colonial supplier of rice and indigo.

But what happened to the cattle?

Through decades of investigation and national collaborations, University of Georgia researchers are answering that question.

A friendship founded on research

When UGA Professor Emeritus Betsy Reitz and former Charleston Museum curator Martha Zierden met at an excavation site in 1979, it was the beginning of a decades-long friendship and partnership steeped in history and archaeology. They met through shared colleagues at Florida State University and the University of Florida later working together on an excavation in St. Augustine.

“I like working with Martha because she had a strong commitment to publication and distributing information,” Reitz said. “It’s one of the best things about working in the context of a museum. Everything you do, ultimately, is going to be interpreted to the public.”

Zierden, a historical archeologist, was working at The Charleston Museum a few years later. When she excavated a site called McCrady’s Tavern in Charleston, she found numerous animal bones. Zierden called Reitz, by then a UGA professor who specialized in the study of animal bones, known as zooarchaeology.

“Originally, we were studying the differences between urban and rural life in Colonial Charleston, but we noticed all of the archaeological sites were full of cattle bones,” Reitz said.

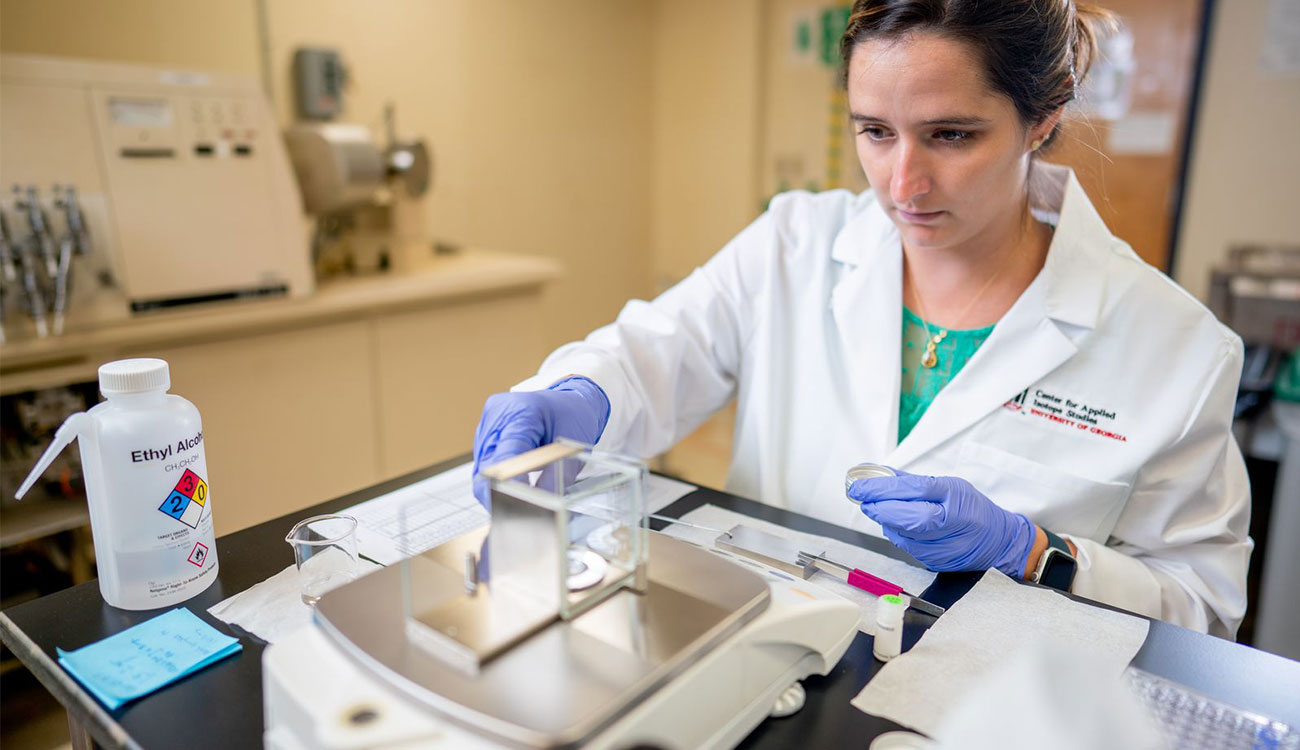

(Left) This is one of seven horn cores found in a 1740s barrel well that was inside what eventually became the Heyward-Washington kitchen cellar. At the time, John Milner, Sr. (1734-1749) lived on the property and operated a gunsmith there. These cores probably were soaking to remove the horn’s keratin sheath but were abandoned for unknown reasons. (Photo provided by Betsy Reitz); (Right) CAIS Assistant Research Scientist Katie Reinberger begins weighing cattle teeth samples for isotope testing. (Photo by Jason Thrasher)

Many historians had believed the Southeastern colonies to be the “kingdom of pork.” Zierden’s discovery, however, told a different story.

“There’s a difference between archaeological insights and historical insights,” Reitz said. “With historical insights, we’re looking at documents that tell us pork was being shipped to colonies throughout the South. Archaeological digs, however, were showing us what had really been used and discarded within the city.”

The more cattle bones they found—particularly at an early Charleston exchange known as the Beef Market—the more Reitz and Zierden saw an opportunity to organize a large, grant-funded interdisciplinary study on the cattle economy of Charleston and the Lowcountry. They wanted to know how cattle impacted the South Carolina landscape and colonial economy, and how that knowledge could be applied to current studies of land use, deforestation, and climate change.

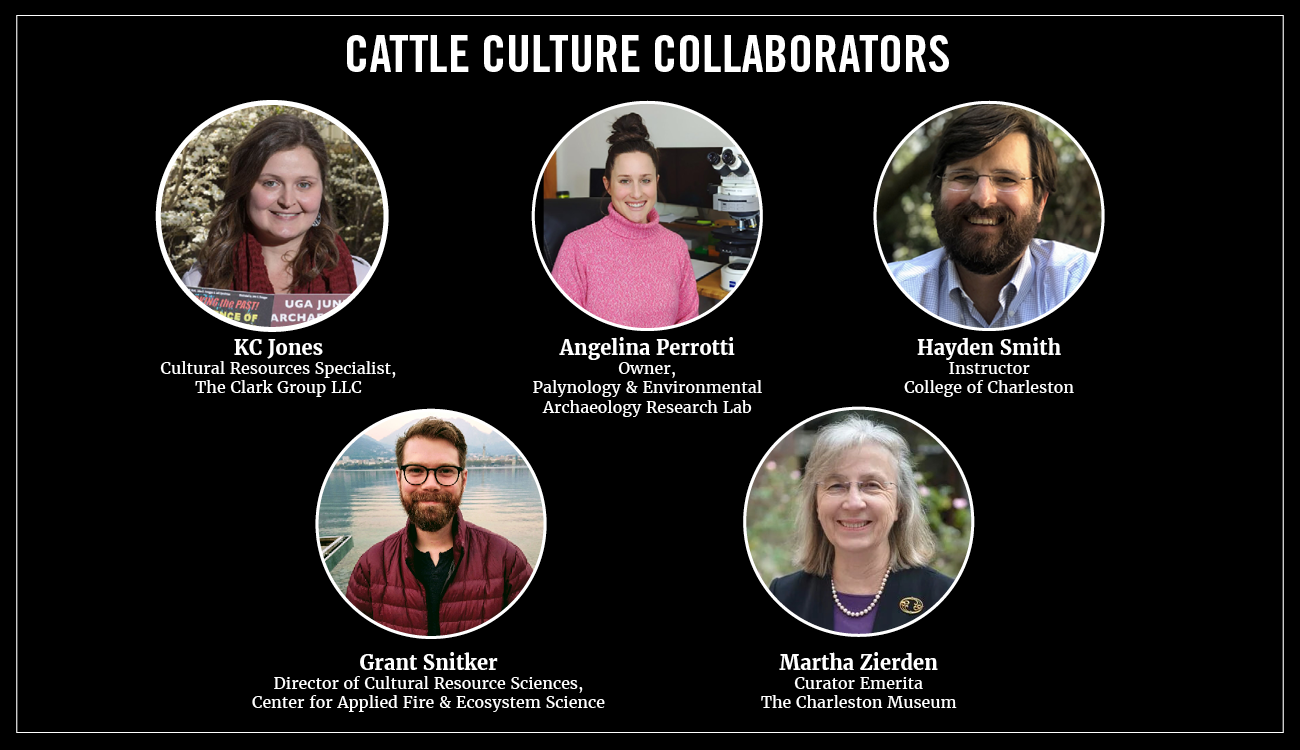

By 2019, when they received initial funding from the National Science Foundation, Zierden and Reitz had accumulated many friends in the archaeology world, most of whom were former students of Reitz, including UGA Center for Applied Isotope Studies Director Carla Hadden. These team members helped broaden the search for effects of cattle on the economic, social, and environmental landscapes.

The team partnered with cultural resources specialist and UGA alum KC Jones, who served as a liaison with the Charleston Museum. Gullah Geechee and Muscogee Creek consultants provided important knowledge on how cattle impacted Indigenous tribes and enslaved Africans.

“This isn’t just colonial history,” Hadden said. “It’s also Native American and enslaved history.”

Cattle in Colonial Charleston

Modern excavations of the area have shown cattle bones were present in both rural and urban areas of the Carolina colony, indicating that many people raised and slaughtered cattle on their property instead of purchasing meat and other products from markets or vendors.

Cattle initially roamed freely on homesteads outside the city; those with crops needed fences for protection from livestock. “Initially, folks were just free ranging cattle near the city, and, over time, they spread inland,” Hadden said. “However, we were surprised to discover cattle were still being slaughtered in the city instead of in the rural Lowcountry.”

During the early-to-mid 1700s, the researchers concluded, Charleston was strongly integrated in the global cattle trade network.

As the colony grew and plantations expanded, Indigenous tribes were displaced by cultural and environmental changes. Environmental archaeologist Grant Snitker and his team found large amounts of charcoal in sediment cores, and palynologist Angelina Perrotti found evidence of cattle dung. They concluded that colonial landowners in rural areas set fire to forested areas to expand grazing for cattle and clear land for crops.

Some Indigenous groups resisted the encroachment of cattle onto their land, while others adapted to the changes and participated in the cattle trade themselves.

Enslaved Africans played a significant role in cattle ranching; some were called “cattle hunters” in archived documents. Many became the primary managers of cattle. Some recognized the Lowcountry’s potential for rice cultivation in the same low-lying areas favored by cattle. This eventually led to the plantation economy that dominated South Carolina for the next century.

Cattle weren’t just being harvested for their meat and hides, according to Hadden. Excavators found a barrel well full of horn cores, likely from gunsmiths who processed cattle horns into powder horns for gunpowder storage. Horns, tallow, and other cattle products were important in the local economy.

Using stable isotope analysis of cattle teeth, Hadden and her CAIS colleagues also determined where cattle were raised. Cattle whose teeth were recovered from Charleston were from multiple sources within the Lowcountry.

“The cattle industry wasn’t one size fits all. Cattle were raised, slaughtered, and transported throughout the region,” Hadden said. “A lot of the landscape modifications from the cattle industry helped make way for the later indigo and rice plantations.”

Eventually, the cattle economy declined as farmers found planting rice and indigo for export was more profitable.

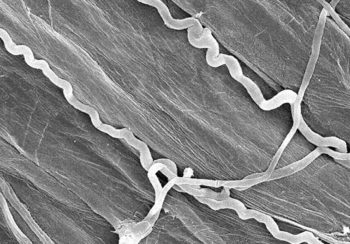

This change was encouraged further when a disease known as “Spanish Staggers” began to spread among cattle in the 1700s.

While the cattle economy is still present, it isn’t nearly as large as it was when the colony was founded in 1670. Cattle still roamed the rural Lowcountry into the early 1900s. Even in Charleston, cattle could still be found in urban markets until they were finally banned from city streets in the 1800s, ending a significant chapter in the city’s long history.

“The cattle industry wasn’t one size fits all. Cattle were raised, slaughtered, and transported throughout the [Lowcountry] region,” Hadden said. “A lot of the landscape modifications from the cattle industry helped make way for the later indigo and rice plantations.”

– Carla Hadden, Director and Research Scientist in the Center for Applied Isotope Studies

Educating the public

From the beginning of their study, Reitz and Zierden prioritized public outreach and education.

In 2023, the Charleston Museum created an immersive exhibit at the Heyward-Washington House, a historic house museum and key archaeological site. Curators added signage that explained the significance of cattle in Charleston and how they were raised at the house.

They also displayed artificial food replicas to teach visitors about common Charleston dishes eaten by 18th century colonists, such as scalded calf head soup.

The Heyward-Washington House exhibit featured replicas of common items found in a Colonial Charleston household, including a cow trough, kitchen appliances, and replica food.

The museum also put together “Bragg Boxes,” named for Laura Bragg, museum director in the 1920s. These are traveling trunks filled with replica artifacts, documents, and activities sent to schools for hands-on education.

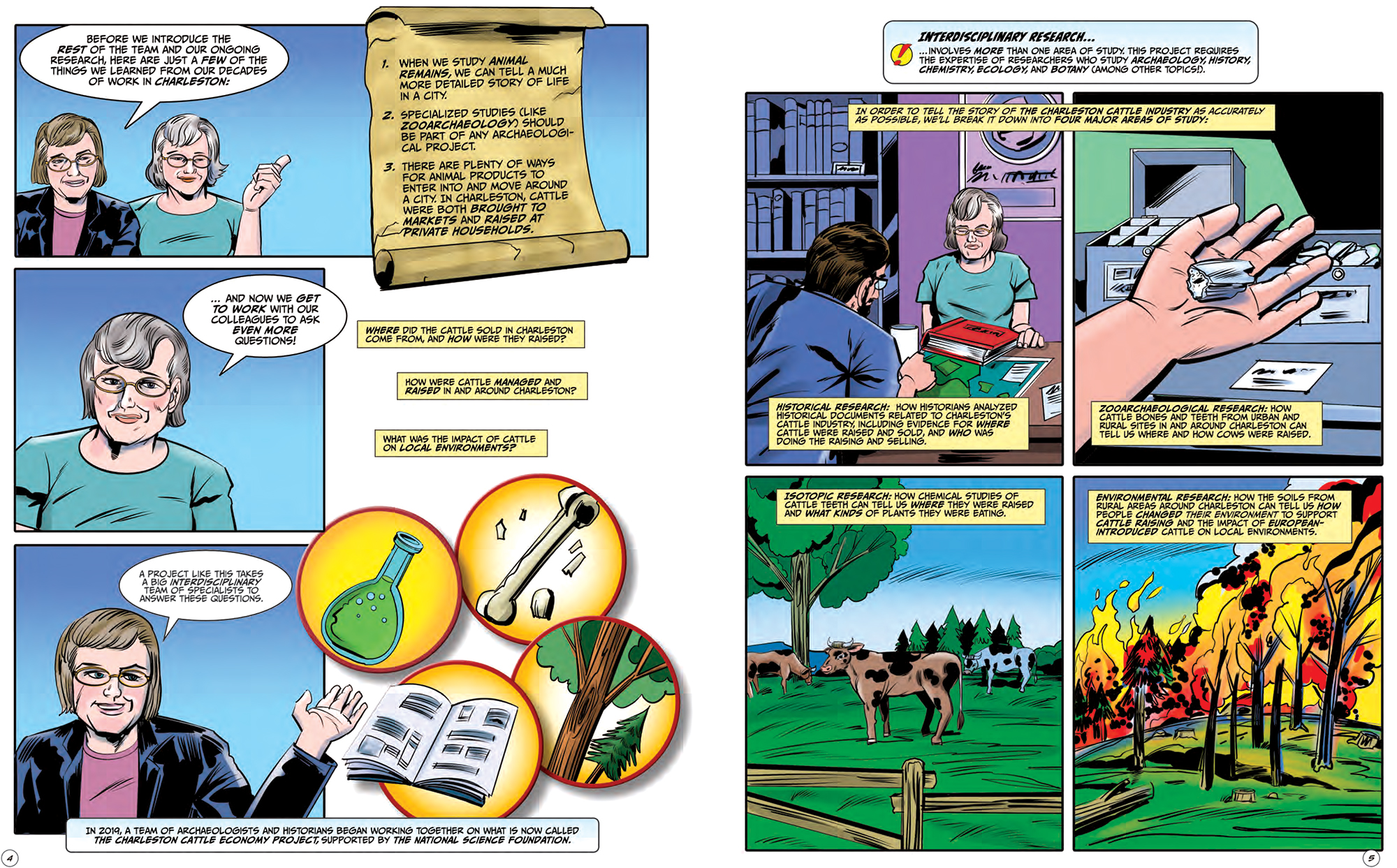

Finally, CAIS released an edition of its educational “Carbon Comics” series that highlights the study, featuring each researcher as a character.

Finally, CAIS released an edition of its educational “Carbon Comics” series that highlights the study, featuring each researcher as a character.

The comic is written in both English and Spanish and geared toward middle and high school students. It explores the intersection of historical narratives and archaeological science to tell the story of Colonial Charleston’s early cattle economy. Its lesson plans align with both South Carolina and Georgia state educational standards for social studies and science.

“I think that’s really been one of the big takeaways is that you can do a study like this and really make it focused on education and showing students how we know what we know about the past and not make it so focused on the science for science’s sake,” Hadden said.

For these outreach and educational efforts, the project was awarded the 2024 Outstanding Public Archaeology Initiative Award by the Society for American Archaeology.

By studying these materials, team members believe they have demonstrated the centrality of cattle in Charleston’s colonial economy and throughout the Lowcountry. The next step is to study the genetic heritage of these animals. Did they originate in northern Europe, in Spanish lands elsewhere in the Americas, or in Africa?

“The materials are archived at the museum,” Zierden said, “so that maybe one day, some bright student will come along and ask the same questions we did.”

When the project began in the 1980s, Zierden and Reitz were working with a collection of 246 animal bones. Today, that number has grown to 135,673, making it one of the largest urban zooarchaeological collections in the country.

“Really, this is just one piece, one peg in this kind of global trade network that we’re starting to look at,” Hadden said. “And maybe one day, someone will answer those lingering questions about the cattle on the Carolina landscape and how they’re connected to cattle in South Carolina and Georgia today.”