Barbara McCaskill grew up in a military family. Her father, Colonel John Lansdon McCaskill, Jr., served in the United States Army throughout her childhood, and her mother, Inez Owens McCaskill, was a registered nurse and military wife. Every 2 1/2 years, they relocated to a new assignment in the United States or Europe, where Barbara adjusted to a new school and made new friends.

“There were long swaths of time when I didn’t have many friends, aside from my younger brother David and my older sister Sandra,” said McCaskill, a Distinguished Research Professor in the University of Georgia Franklin College of Arts and Sciences Department of English. “So I turned to books.”

She fell in love with all the classics—books like Lewis Carroll’s “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland,” which she read over and over. They became a form of continuity and connection across those constant life changes.

Her parents, both Black Southerners who grew up during segregation and Jim Crow, and many of her teachers had personally participated in the 20th century Civil Rights Movement. They emphasized education and gave her a nuanced understanding of her history.

She entered college knowing she wanted to teach and write. By the time she finished her doctorate at Emory University, being in a classroom felt natural to her.

“I like seeing my audience. I like going into a classroom and I like the exchange with students, whether they are the traditional 18- to 25-year-olds or older adult learners,” McCaskill said. “I love the exchanges that we have, sharing opinions and analyses and interpretations about the literature that are not necessarily my own.”

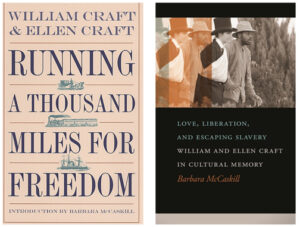

As she dove further into academia, she also discovered a love of research. While working as an Aaron Diamond Foundation Fellow at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture at the New York Public Library, she took a particular interest in the story of William and Ellen Craft, a married couple who escaped slavery in 1848 in Macon, Georgia.

Around that time, she joined UGA’s English faculty, citing the benefits of being in a place that was relevant to her research.

Research epiphanies

McCaskill’s research career can be defined through several turning points, epiphanies that helped hone her sense of audience, collaboration, method, and mission.

She was captivated by the story of the Crafts, who emigrated to England for 19 years, becoming writers and abolitionists following their escape from slavery.

However, gaps in the couple’s history couldn’t be found in archives, a pervasive issue many historians encounter studying Black writers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

McCaskill wasn’t deterred. Instead, she turned to the Crafts’ descendants for the rest of the story.

“I did [it] with a great deal of hesitation and fear because I was worried they might not want to work with me,” McCaskill said. “But it turned out to be a very generative relationship.”

Her first outreach in the 1990s sparked deep collaboration. She’s worked closely with multiple generations of the family—giving joint talks, sharing findings on a family listserv, and ultimately forming what she calls a “new family.”

Now, McCaskill continues to dedicate her career to recovering stories and works of Black authors from those lost years.

“So many of the stories of enslaved people have disappeared… My goal is to try as much as possible to fill in those gaps and to tell those stories and imagine what their lives were like based on the stories that we have,” she said.

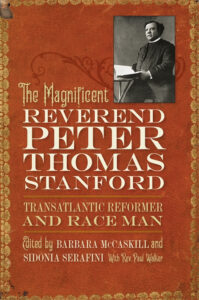

Her next big project focused on Rev. Peter Thomas Stanford, a formerly enslaved preacher, writer, and orator who emigrated to Great Britain following his escape. McCaskill co-authored a book on Stanford with then-graduate student Sidonia Serafini—now a tenure-track assistant professor at Georgia College and State University—who brought fresh perspective to McCaskill’s methods.

“There were questions I wouldn’t have asked if it wasn’t for her,” she said. “Since she didn’t have as much experience working on African American literature, she wasn’t as tethered to some preconceptions as I was.”

Stepping outside her comfort zone

As her career progressed, she was surprised to learn that so many outside academia were interested her work. Prominent members of various church groups and other community organizations around Georgia would ask her to come and give talks.

This prompted her to place more emphasis on public humanities education—something that plays a major role in her position as associate academic director of the Willson Center for Humanities and Arts.

“I try to be available to high schools, to community groups… I’m part of a local branch of the national Association for the Study of African American Life and History, founded in 1915 by the Black historian and Harvard graduate Carter G. Woodson, where the whole reason for our being is to disseminate African American history, culture, and literature,” she said.

When the Willson Center received a four-year, $1 million Higher Education Grant from the Andrew Mellon Foundation, McCaskill got the opportunity to partner with the Penn Center National Historic Landmark District, a historic school founded in 1862 for formerly enslaved communities and dedicated to preserving Black history and Gullah Geechee heritage.

Through this project, McCaskill learned how to curate museum exhibits, organize domestic residencies for students, and design public programs for all ages.

“It’s really opened a new pathway for me… How do we present African American art and culture as part of the American story, but also as unique and different from it?” she said.

Though she began with 19th century African American literature, McCaskill brought together her two favorite parts of her career when she began working on the multiyear Civil Rights Digital Library—a collaborative, student-centered, public-facing humanities research initiative funded by the Institute for Museum and Library Services.

Working with both undergraduate and graduate students, as well as UGA archivists and librarians, McCaskill and her team created a comprehensive online resource that provides access to digitized materials from collections throughout the US documenting the American Civil Rights Movement, including primary sources and historical news footage.

“It wasn’t a leap for me at all to do work on the civil rights era… because when I talk about the stories of people like William and Ellen Craft, I have to contextualize their stories in relationship to the larger civil rights struggle,” she said.

Because of this project, the “Andrew Young Presents: How We Got Over” documentary, which showcases the library’s resources and the desegregation of southern schools like UGA, won a regional Emmy Award in 2010.

She describes this as a kind of intellectual full circle—linking her research on slavery with later civil rights struggles, reinforcing her conviction that history is continuous.

Scholarship that endures

McCaskill will be the first to tell you that teaching has given her a lot of humility—but it remains her greatest legacy.

“I’ve had to learn to not be so wedded to being right, because sometimes I’ve been wrong,” she said. “The sky will not fall if you are not right.”

One size doesn’t fit all when it comes to academic careers, according to McCaskill, and she encourages her students to be bold and forge their own paths in academia. By stepping into disciplines like history, preservation, and curation, she has been able to expand the impact of her work beyond literary analysis.

Ultimately, McCaskill views literature as a vehicle to create a better world for everyone.

“Literature exists in the realm of possibility—but suggests that possibility can become reality,” she said.