It’s a Tuesday morning in September at the Georgia Museum of Art, and the front doors have only just opened to the public. A handful of guests quietly make their way to the galleries upstairs, basking in the cool air after leaving an already hot day beyond the glass doors outside.

There’s an unspoken sense of decorum most appear to feel as they wander the halls, viewing the art on display and whispering to each other, presumably to comment on a piece—perhaps the subject or artist themselves, or maybe a more nuanced observation of composition or style.

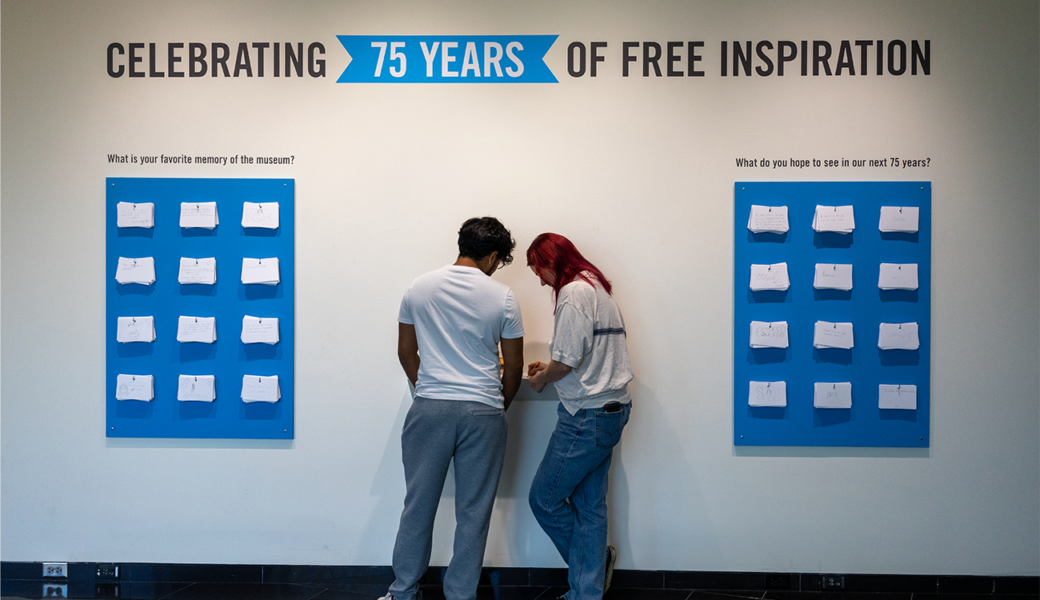

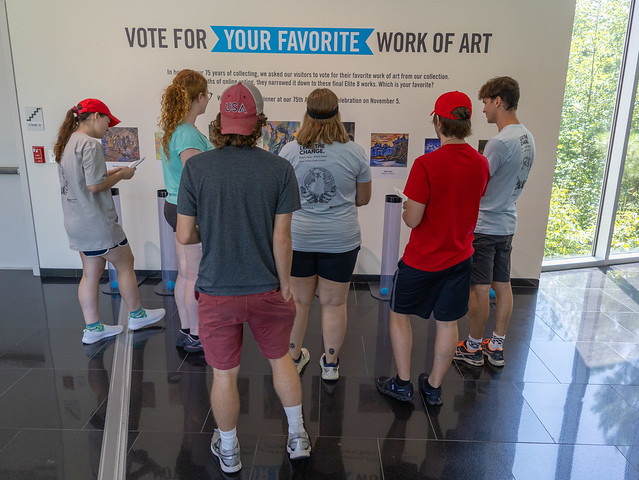

On the wall hangs a display of index cards under a pair of headings: one asking for visitors’ memories from the museum’s first 75 years, which it celebrated at an anniversary event this month, and the other their hopes for the years to come.

“Seeing all the different emotions in the artwork and learning more about humans who came before us,” one card said under the memories.

“Being with the love of my life, surrounded by my passion,” said another.

It’s a small snapshot of a University of Georgia fixture that means something different to each of the thousands who walk its galleries each year. There are other places to experience art in Georgia, said Lamar Dodd School of Art Director and Professor Joseph Peragine, but this museum is different.

“It’s not an opportunity you get everywhere else,” he said. “To have a foot in the exhibition space, the academic and the research is incredibly unique.”

As the museum celebrates 75 years inspiring students, it’s worth exploring the enormous impact it has had on UGA and its academic community, from the extensive collections to the on-campus partnerships, to an ever-expanding role in the university’s research ecosystem.

Georgia Museum of Art

75 YEARS OF FREE INSPIRATION

Use the arrows to navigate through the timeline.

An art museum is an enterprise of inquiry

In 1967, the museum housed the “Eyewitness to Space” exhibition, which featured 69 paintings, drawings and watercolors by 17 artists who had been invited to Cape Kennedy by NASA to record impressions of the historic events taking place in the space program.

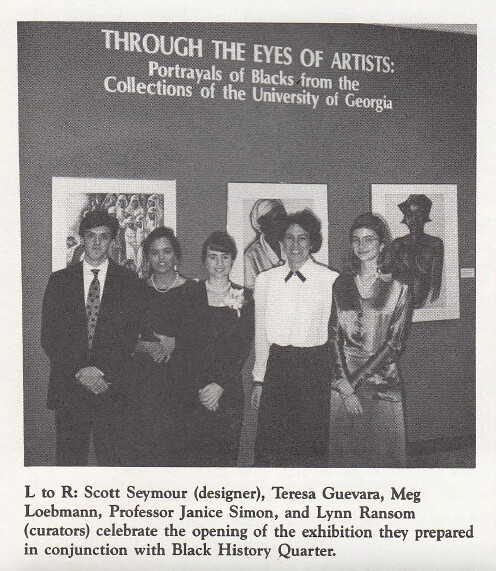

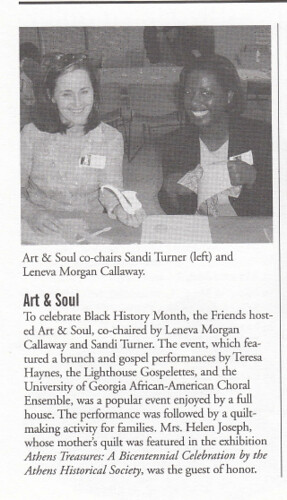

In later years, it tackled important social issues like the AIDS epidemic with the creation of a digital AIDS Quilt and brought more diverse cultural perspective through exhibitions that focused on international, African American and women artists’ work.

Both are evidence of the efforts museum directors, curators and researchers make to reach across disciplines to convey meaning to the public.

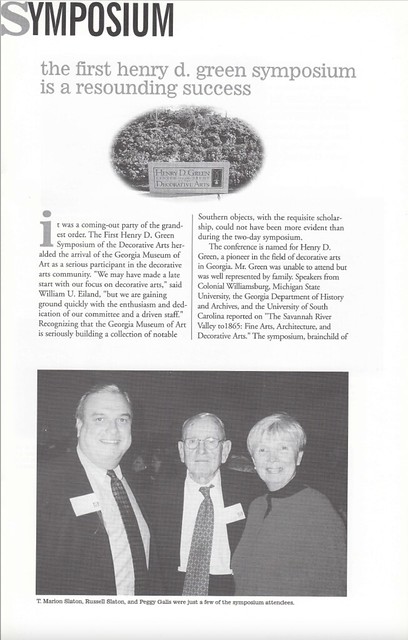

“Research for the museum involves objects or events, and those have meaning that is sometimes elusive,” said William Eiland, who stepped down this year after serving 33 years as the museum’s director. “Research is locating that elusive fact or idea that can lead you to it.”

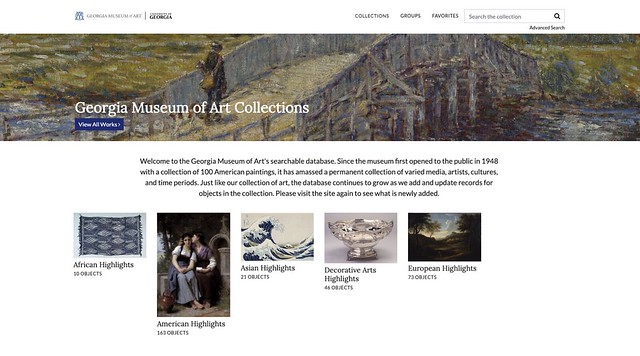

Art research at UGA and the Georgia Museum of Art runs the gamut of exploration: identifying cultural significance based on a piece of art’s historical context, but also how it was made, how it traveled over time, how it was preserved and how its meaning changed over each of these points of reference.

“Outside the museum, you might ask, ‘Is this beautiful?’” said David Odo, who took over as museum director in August after a winding career path that most recently had him at the Harvard Art Museums at Harvard University. “But that word is incredibly rich and complex. It’s not the only thing art historians are interested in. The research is very deep and wide.”

It involves historians, yes, but also people like chemists, who explore materiality and processes by which to conserve art objects for the future, and philosophers who help answer questions about how the piece’s changing composition impacts its meaning entirely.

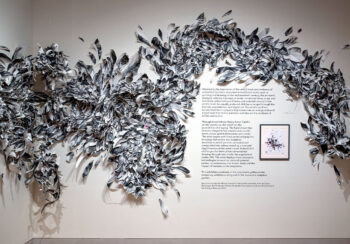

Today, that also involves computing researchers and digital artists, whose canvases have transcended the analog. Currently on display is an exhibition called “Nancy Baker Cahill: Through Lines,” an exploration of Baker Cahill’s progression from drawing to digital works and augmented reality. One piece, “Margin of Error,” is an entirely augmented work in the museum’s Jane and Harry Willson Sculpture Garden.

“Innovation is inherent to art making,” Odo said. “We can’t ignore what artists are doing with technologies like augmented reality or AI. It’s an important thing for museums to engage in.”

Odo wants to grow the museum across campus during his time at the helm. There are inherent connections with departments like sociology, communications, anthropology, psychology, English, philosophy or chemistry. But he envisions partnerships with domains not typically considered when thinking about art. The University of Georgia-Augusta University Medical Partnership is one potential area of emphasis.

The idea, he said, is that while medical professionals are called upon to be precise in their work diagnosing or treating patients, there is room to help them embrace ambiguity.

“In medicine, the stakes are different,” Odo said. “And yet ambiguities exist. So, how do you as a physician learn to tolerate and grow from that? Giving them a space at the museum to experience that meta cognition around these complicated issues, I think, helps them approach their work in a way that’s easier for them to tolerate.”

From canvas to campus

If research is the lifeblood of an academic museum like the one at UGA, then students and their classrooms are the heartbeat that distributes the impact to the university and state.

Caroline Young has seen this firsthand. When she began lecturing in UGA’s Department of English in Fall 2019, she was involved with Common Good Atlanta, a prison education program across sites in North Georgia where instructors brought college-level education to various prison facilities.

In addition to teaching her UGA students, Young was also working with the Whitworth Women’s Facility in Hartwell and saw the Georgia Museum of Art as a resource for both.

“It was such amazing resource our students had here at UGA,” she said, “and one not available to our prison classes. I was an art history major a million years ago, and it’s always been a love of mine. I wanted to find a way to bring the museum to them.”

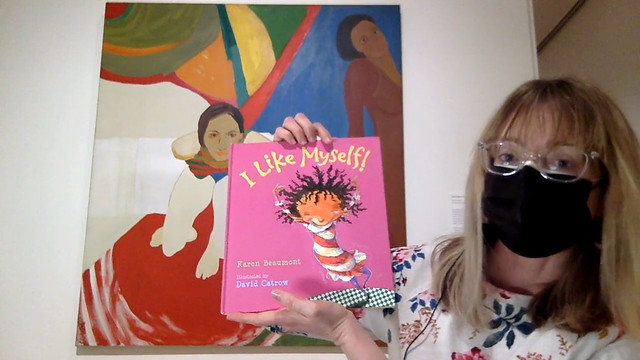

In August 2020, Young reached out to Callan Steinmann, then an associate curator of education. Now the head of education and curator of academic and public programs at the museum, Steinmann mentioned her time working with elementary students. She would bring images from the museum, scans of the artwork for young students to peruse and examine, learning how to identify and appreciate various works.

With the help of Callan Steinmann, now head of education and curator of academic and public programs at the museum, Young created a project in which UGA students could identify work from the museum’s archives to share with the women at Whitworth. They explored the trove of artwork no longer displayed to the public.

For the first iteration of the project, they selected 60 works from the permanent collection and 40 from the archives, representing a diverse mix of artists, including African Americans and women, artists from the South, and more. UGA students compiled information about the works, researching background about the art and artist, as well as the historical context.

“It was like a deconstructed textbook,” Young said.

At Whitworth, students took a piece from this compilation and wrote an essay or poem in response. Museum curators saw the works that had been pulled from the archives and turned the project into an exhibit.

Curated by Steinmann, “Art is a Form of Freedom” was displayed this year from March 4-July 2. The exhibit won a silver award in the Under $10,000 Budget category at the Southeastern Museums Conference.

“I have never met two communities that gained more from being near each other,” Young said. “It took me back to why I began writing poetry: getting the academics out of it and just reflecting.”

Peragine, who earned his undergraduate degree from UGA in 1983, returned in 2022 for this kind of collaboration. He pointed to the UGA Arts Collaborative, which involves the museum, Graduate School, Franklin College of Arts and Sciences, Willson Center for Humanities and Arts, the Arts Collaborative Student Organization, the Alliance for the Arts in Research Universities, and other organizations that foster an ecosystem of artistic inquiry on campus and beyond.

Funded by grants from these organizations and others, the Collaborative is a catalyst for interdisciplinary creative projects, advanced research and critical discourse in the arts. It began in 1999 as a series of conversations among faculty and officially launched in 2001 with seed funding from the Office of the Provost.

It’s partnerships like these, Peragine said, that make the arts community at UGA so unique.

“It’s vital,” he said. “If we’re just in our bubble making works and not engaging and connecting with it, we’re lost. Our faculty are very engaged in these collaborations and research, interested in current events and sciences. All these things play into how we look at art, and artists have an important role to play in the ethics and communications of these issues.”

A place to reflect

Beyond the academics and the research, Odo also sees the museum simply as a place for people to come reflect. Whether in a high-stress field like medicine or not, it’s a place people can embrace knowledge and exploration while also escaping the rigors of their daily pursuits.

Peragine makes a point to do this himself.

“Every time I go to the museum, I notice something different,” he said, noting he visits at least once each month. “Wandering without an agenda is a bit like scrolling on your phone. You might find a rabbit hole to follow.”

Or, if you’re like Annelies Mondi, you might return to the same place over and over again. Mondi, a longtime leader at the museum who spent a few months as interim director earlier this year and currently serves as senior advisor to Odo, said she loves to get out of the office and walk through the museum’s peaceful galleries.

Her favorite painting is called “Fog Breakers” by George Bellows, a 1913 painting depicting waves crashing against a cliff shoreline.

“I stand there, maybe after a tough day,” Mondi said. “I see these ocean waves against the rocks, and I almost feel the spray in my face. I never get tired of that.”

Neither has the UGA community, which has helped support the museum for 75 years. It’s a fruitful relationship, as the hundreds of index cards expressed, they hope will continue for another 75 years and beyond.