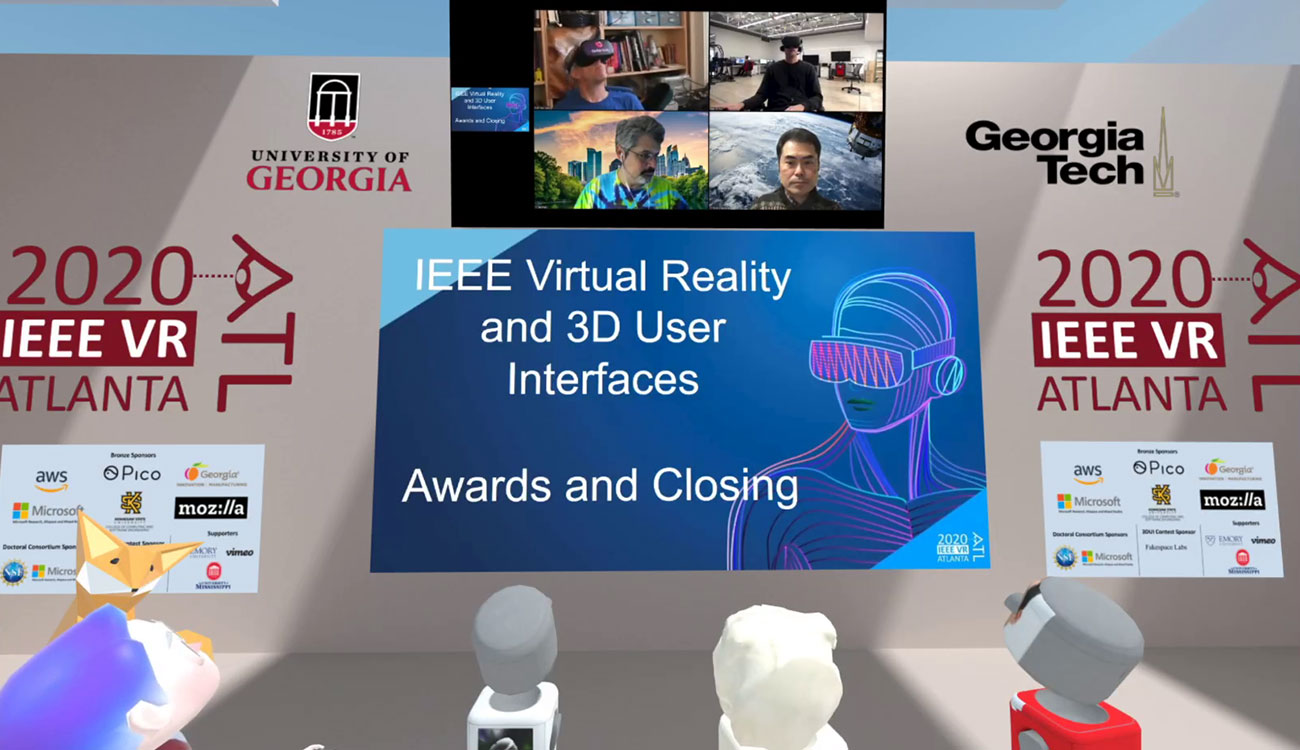

To make it happen, Johnsen and the conference planning team used a combination of video conferencing, live streaming and virtual reality, supplemented with the instant messaging platform Slack and the Q&A platform Slido. It took a small army working nearly around the clock for two weeks, but it was worth it, Johnsen said the morning after. The five-day conference went off without a hitch. And he’d finally gotten more than four hours of sleep.

The weeks leading up to the conference were intense, but in some ways the virtual reality field has been poised for years to take on this kind of challenge. All the organizers needed was a good reason to take advantage of existing technologies, and they got one: COVID-19.

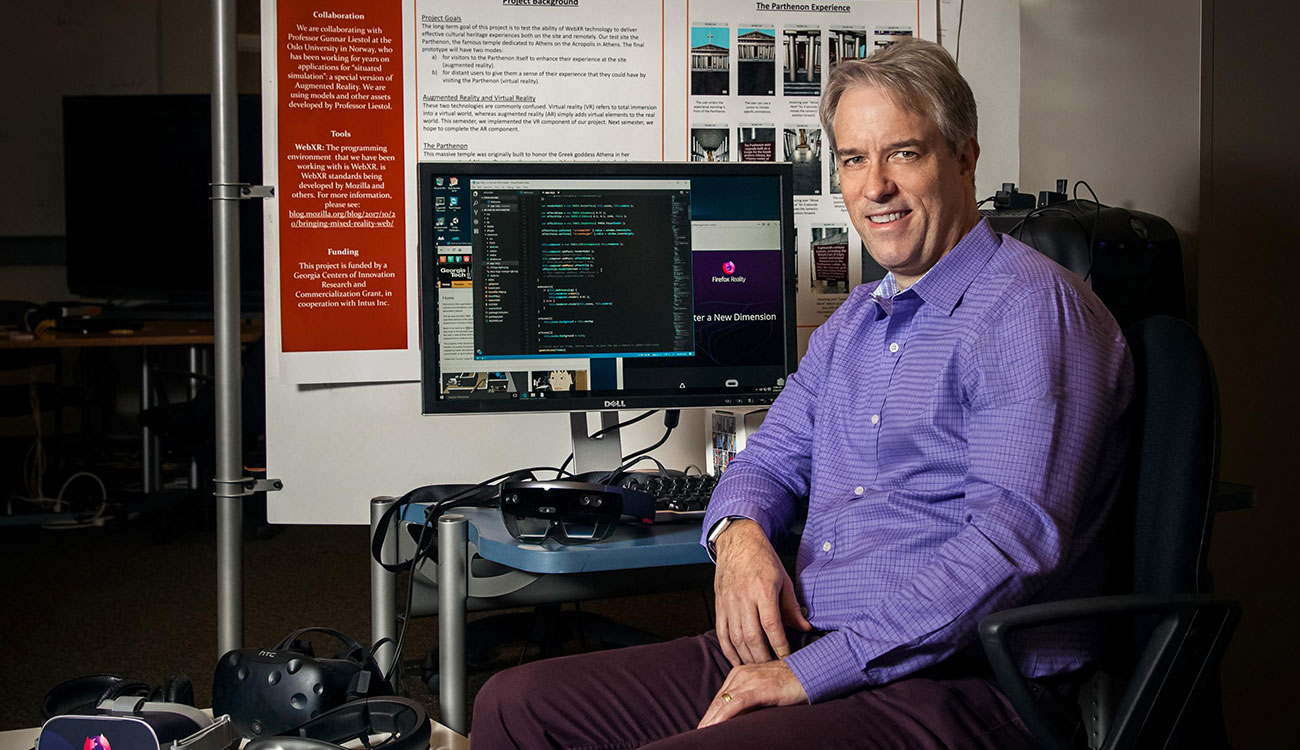

“There was no real reason to pull the trigger on it before,” said Johnsen, associate professor in the College of Engineering. “We knew that we had an opportunity to really try this in an authentic way. We put in an absurd amount of time and got it done because, at some level, we were making history, and that was cool. It was worth it.”

The Women in MR session allowed women working in virtual reality, augmented reality and mixed reality—a combination of VR and AR—to network and explore the possibilities of VR in social settings. They also experimented with conjuring VR objects to play with, including cheese boards, bottles of wine, flowers, pugs and beluga whales. (Video without sound courtesy of Sun Joo “Grace” Ahn)

Getting ahead of the curve

In late February, Johnsen and his three co-chairs—Blair MacIntyre (Georgia Tech), J. Edward Swan II (Mississippi State) and Kiyoshi Kiyokawa (Nara Institute of Science and Technology, Japan)—were watching news of the spread of COVID-19 with growing concern.

Large conferences were being canceled, including the Game Developers Conference scheduled for March in San Francisco. Even conferences scheduled for May, like the Mobile World Congress in Barcelona and Facebook’s F8 Developer Conference in San José, were canceled and postponed, respectively.

In the latter half of February, the new coronavirus spread from China to Europe, Asia, Africa and Latin America. On Feb. 28, the U.S. recorded its first COVID-19 death, in Seattle, and placed restrictions on travel to some international locations. For the conference organizers, the question was not if coronavirus would arrive in Georgia, but when.

“We saw this coming. The overwhelming odds were that we were going to have to cancel the conference or that it was going to be a subpar experience,” Johnsen said. “We thought, ‘If we start focusing now on taking it online, we can do a good job with it. If we have to cancel or switch to this a week before, the conference just isn’t going to happen.’”

For MacIntyre, ethical considerations were a big part of the equation.

“At that point, there would have been a lot of people who would have come because they had a paper in the conference and felt pressured to be there,” he said. “It felt wrong to put people in the situation of having to choose between their careers and worrying about their health.”

By March 1, they’d made the decision to move the Atlanta-based conference online, although it would take another week to get official approval. On March 7, they notified the IEEE community and starting planning in earnest. They had two weeks to transform the small online component that was already planned—for a couple hundred people—into a platform that would eventually support more than 2,000 registered attendees and touch every aspect of the conference.

Everything had to be reconfigured for the digital world, including 450 refereed submissions that would end up in the conference’s digital library. Committee chairs, who had already taken care of their obligations, were asked to help with the shift in plan.

“Everybody stepped up,” Johnsen said. “Nobody said no, and nobody complained.”

MacIntyre put out a Twitter call for volunteers; 100 people signed up to help. The team got tremendous support from IEEE, Mozilla (whose Hubs platform was the foundation of the online experience), and their respective institutions. Johnsen is particularly grateful for UGA’s support, including giving special permission to run the conference from his Virtual Experiences Laboratory despite the campus’ reduction to essential activities.

“The biggest concern we had was that the internet would not work. If the internet was unstable, it would completely fail,” he said.

“Anything I asked UGA for, I got. That was really amazing.”

“Even though we are physically distant, there is still a great need to connect. Virtual reality provides us with another tool in the tool set to creatively connect with one another while maintaining physical distance.”

– Sun Joo “Grace” Ahn, director of UGA’s Games and Virtual Environments Lab

(Photo by Andrew Davis Tucker)

Not quite Spielberg

Three days before the IEEE conference, Sun Joo “Grace” Ahn was a yellow robot with waving hands. The team was conducting a test run in virtual reality, and she was trying a function that would allow conference-goers to take selfies in VR and post them to Twitter.

“There will be a learning curve for most attendees who have never been in virtual reality before,” predicted Ahn, publicity co-chair for the conference and associate professor in the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication. “Learning to operate the controls will take time. You will definitely see some people stuck in the corner who can’t figure out how to get out.”

The organizers had planned for such outcomes, ensuring that plenty of volunteers, conference staff and Mozilla staff would be available to support users accessing content via VR headset, desktop, laptop or smartphone. Ahn compared learning a new interface to what happens when you upgrade a smartphone—except with less time for design on the developers’ end.

“The team did an amazing job creating the virtual space, especially in such a short time frame,” said Ahn, who advised looking for the promise of the technology but not expecting perfection. “This is a historic moment. We are reshaping how people think about conferences. But it’s not going to look like ‘Ready Player One.’”

Just one week later, Twitter reviews of the IEEE virtual reality experience were extremely positive.

“Having a wonderful time in the Hubs! Meeting friends, taking selfies, watching streams and finding Easter eggs,” tweeted Eric Lu, a Ph.D. student at Virginia Tech.

“Amazing experience!” tweeted Tim Chen, a senior lecturer at the University of Adelaide, Australia. “The IEEE VR organisers have done a tremendous job of showing us the future of conference!”

“The Three Streams Conference Hubs Room has to be the coolest space at #IEEEVR2020,” tweeted Vinoba Vinayagamoorthy, a project R&D engineer with BBC. “It’s beautiful. Tomorrow I am visiting in the Oculus Quest to see if I feel as small as a bug in there.”

MacIntyre worked closely with Mozilla Hubs, the platform for the virtual reality portion of the conference. The Mozilla team hacked a custom version of their software to make everything work, and they were able to continuously revise the system.

“If you want to see a web page, you go to it and it downloads from the server. The entire virtual world experience is fed that way, so they can send a change, and the next time someone goes into one of the rooms, they get the new version,” MacIntyre said. “We’re able to keep revising the way things work, fixing bugs and changing the setup as the conference is going on, which is just phenomenal.”

The relative anonymity of virtual reality also made it easier for some to socialize, according to Johnsen.

“It’s a known result in the virtual reality community, and we’re living it now,” he said. “It’s such a cool thing to see these things play out in real life.”

Keeping their peers’ personal lives in mind, the planning team deliberately didn’t schedule any social events. They wanted conference-goers, particularly those in distant time zones, to be able to take advantage of the perks of an online conference—like still getting to tuck their kids in bed at night.

“We didn’t orchestrate any social events intentionally, and they still happened,” Johnsen said. “People still took the time to meet up with colleagues.”

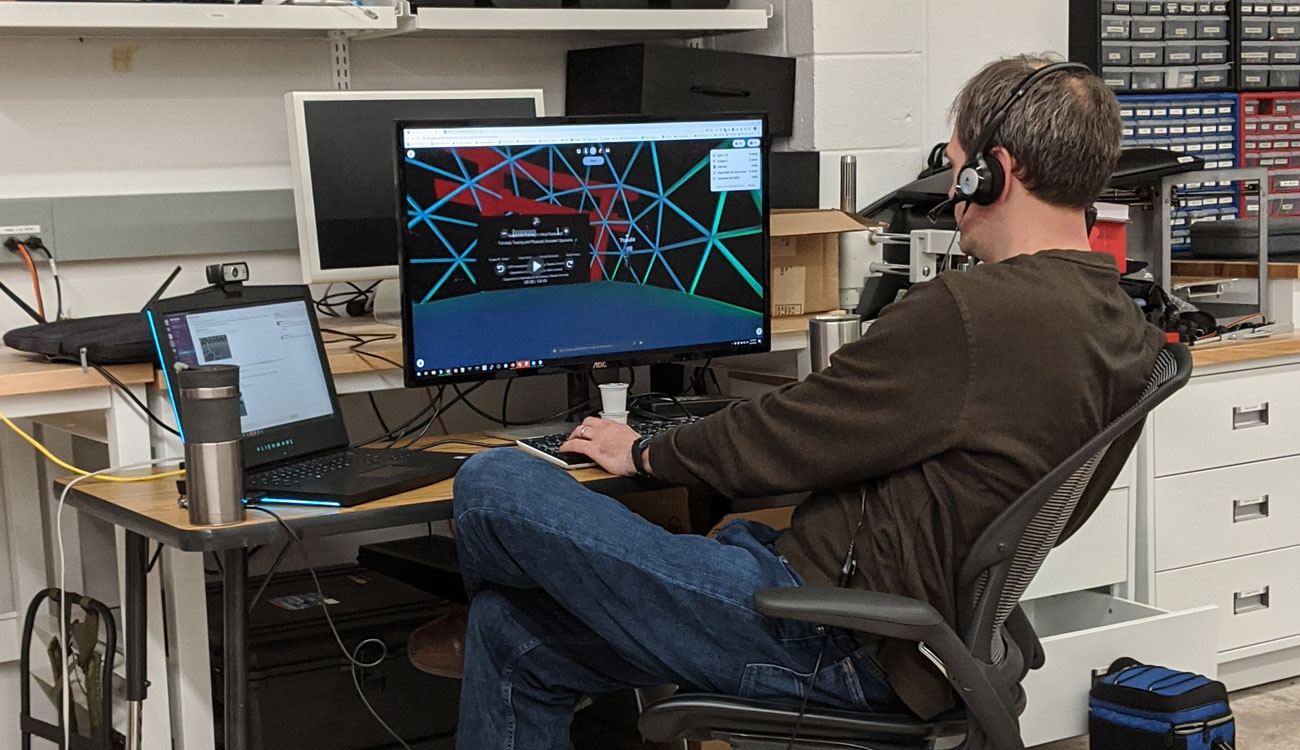

Johnsen and six students ran the back end of the five-day event from his Virtual Experiences Lab, getting special permission to be on campus despite the reduction to essential activities. This photo of the lab was taken before the spread of COVID-19; during the conference, each student had a dedicated workspace, followed social distancing protocols, and worked in shifts of three or four. (Photo by Anton Franzluebbers)

The beauty of being flexible

Johnsen can tell you the exact moment when he started to feel better about the conference team’s monumental task. It was during the first week of March, when he asked his students for help, and they stepped up.

He and six students ran the back end of the conference from his lab, handling the video portion that was livestreamed through Zoom then re-broadcast via Twitch. The team included grad students Anton Franzluebbers, Catherine Ball, Brook Bowers, Andrew Rukangu and undergraduate A.J. Tuttle, as well as grad student Scott Guthrie, part of Ahn’s team at the Games and Virtual Environments Lab.

Despite the need to work in the same location, the students followed social distancing protocols. Everyone had their own dedicated work station, and they worked in shifts, with three or four coming in at a time. When not at the lab, they monitored the operation online.

“Anything that went wrong, at any point in time, my students would jump in and take care of it,” Johnsen said. “I don’t know how it would have run without them.”

After Johnsen’s students were on board, but before the conference started, registration was capped at roughly 1,750 with a waiting list. The organizers wanted to make sure the infrastructure would hold, and it did. By the end, the final registration of more than 2,000 quadrupled what they would have expected if they’d stuck with an in-person conference.

Johnsen threw out a few more conference statistics: 10,000 messages were sent via Slack, 850 questions were asked, and 500 people were watching the talks at any given time.

“A lot of people chose to watch all three streams on Twitch together at the same time. People often want to casually observe what’s going on and maybe jump in and listen to one that they’re more interested in, or do some other work while they’re paying attention,” he said. “The internet affords you that flexibility. You’re not stuck in a room and being forced to listen or to very obviously ignore what’s going on.”

Looking ahead, Johnsen is excited to see what the conference team can do for 2021. Having a year to think about it seems like a luxury.

“The interface is always going to be a hurdle, but the cool thing is that now we’ve developed some expertise,” he said. “The next time we do this—which hopefully won’t be by force, but will be by choice—we’ll be even better at it.”

Additional reporting by Mike Wooten