When Samantha Joye and Rebecca Rutstein talk about diving in the deep ocean, it can be difficult to tell who is the scientist and who is the artist.

“There’s this sense of purity, like looking at a newborn baby. There’s this sense of awe that you get again and again during a dive,” Joye says. “But especially as you’re going down to the bottom—it’s overwhelming. You bare your soul in that submarine.”

“Going up and down in the water column was probably the most spiritual thing I’ve ever experienced,” says Rutstein, noting the movement of bioluminescent organisms that looked like “dancing stars” in the pitch black.

“My jaw dropped to the floor. I just couldn’t believe what I was seeing.”

Technically, Joye is the scientist, and Rutstein is the artist. The two came together for a public discussion during the Alliance for the Arts in Research Universities conference held on UGA’s campus in November.

Scientists and artists don’t generally work together, so their paths might never have crossed. But Joye, a marine scientist and Georgia Athletic Association Professor in the Franklin College of Arts and Sciences, and Rutstein, a Philadelphia-based artist, have a lot in common. Both are self-described geology nerds. Both are curious about how our planet works and eager to explore places hidden from view. And both feel compelled to share what they learn. Their commonalities are apparent as they discuss their work.

Joye: “The perspective is amazing. I think you feel your humanity…”

Rutstein interjects: “You feel tiny.”

Joye: “… when you’re in the submarine. You feel [that] you’re a little speck in this incredibly diverse universe.”

Rutstein echoes the sentiment: “You’re a speck.”

Their conversation coincided with the opening of a year-long installation of Rutstein’s work at the Georgia Museum of Art, part of her tenure as the third Delta Visiting Chair for Global Understanding, established by UGA’s Willson Center for Humanities and Arts through support from The Delta Air Lines Foundation. The Delta Chair hosts outstanding global scholars, leading creative thinkers, artists and intellectuals who teach and perform research at the university.

“The scale and diversity of UGA offer constant opportunities to put different kinds of human knowledge and creativity in conversation with each other. The Willson Center is a hub of these partnerships in which the arts, the humanities and the sciences can speak to and with each other about experiences that change how we see our world,” says Nicholas Allen, Willson Center director and Franklin Professor of English. “In this case, our Delta Visiting Chair allowed us to bring Rebecca to campus to talk about her deep-sea explorations with Mandy and to show the outcomes of that work in her sculpture and painting.”

A few weeks after their joint appearance, Joye and Rutstein embarked on a deep-sea expedition, taking a dive together in the Alvin, the country’s only research submersible capable of carrying humans to the sea floor. For Rutstein, it’s the fulfillment of a lifelong dream. For Joye, it’s an opportunity to share something special, but inaccessible to most, with an artist—someone who can translate the experience into work that will resonate with the public.

“I think this [partnership] could have a huge impact on how people see the deep ocean,” she says.

Joye, who is known internationally for her work in the Gulf of Mexico after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, has spent close to two months of her life on the bottom of the ocean (an estimated 50 to 100 dives). But it never gets old.

“I’m never going to stop discovering things,” she says. “I’m never going to stop seeing things that make my jaw hit the floor.”

After each dive, she comes back with many new ideas—and an altered outlook.

“You ever wonder what limits your imagination? Diving in submersibles and working in the ocean blasts through those walls,” she says. “You’re constantly going past your boundaries and thinking about how the world works in new and different ways.”

Joye wants to share that “gift of expansion” with others. Research at sea is a collaborative venture, she says, and everyone needs to be committed to communicating about it.

“Not everybody’s meant to be an oceanographer,” she says. “Not everybody’s meant to be an artist at sea. But for the average person, this opens their mind and their spirit and ignites their imagination.”

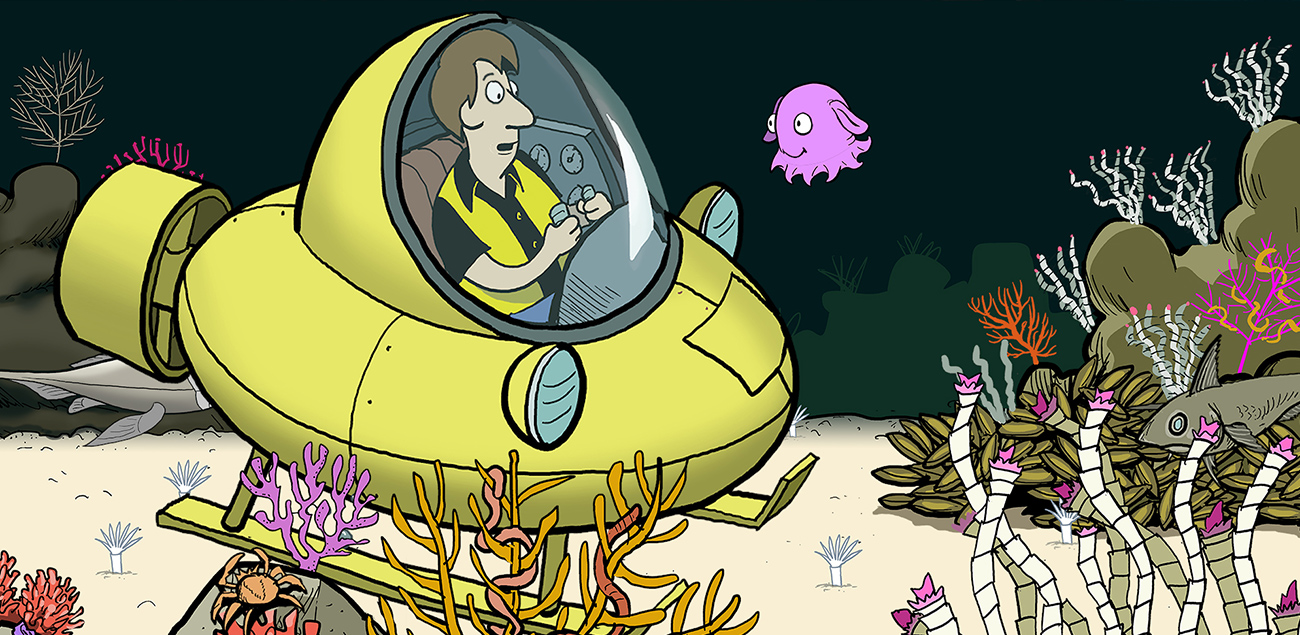

Joye’s commitment to education led to another project that debuted in November, “The Adventures of Zack and Molly,” a three-part animated series highlighting the Gulf of Mexico and the importance of healthy oceans. The short film series, aimed at kids, was created in partnership with artist Jim Toomey, creator of the “Sherman’s Lagoon” comic strip.

Originally a painter, she had always been interested in geology and began exploring specific locations—including the Canadian Rockies and Iceland—through her art. She’d focused on land-based phenomena, but while studying Kilauea Volcano in Hawaii, she came across a sonar map of the ocean floor around the islands. It was a “eureka” moment.

“‘I’m looking at the tip of the iceberg. There’s this whole world underneath that is even more interesting,’” she remembers thinking. “I became fascinated by the ocean floor, this imagined space.”

Rutstein’s 2008 piece “Abyss” pays tribute to Marie Tharp, an American geologist and oceanographic cartographer who helped create the first scientific map of the Atlantic Ocean floor.

During her 2012 residency in Iceland, Rutstein began creating objects based on topographical forms in her paintings. She had the forms laser cut out of steel and then bent them with a blowtorch, leading to works like “Sky Terrain” (2015), an outdoor installation on the Temple University campus.

But it was her first artist-at-sea expedition, when she sailed from the Galapagos Islands to San Diego in 2015, that really had an impact.

“I felt like I was at home, at peace, out at sea,” she says. “From that moment on, I knew that this was going to be the trajectory of my creative practice.”

Rutstein has since embarked on four more artist-at-sea expeditions, with a fifth scheduled this year. She enjoys setting up her studio on a ship, feeding off scientists’ energy as they take turns looking at samples under the microscope.

“It’s a constant flow of inspiration,” she says.

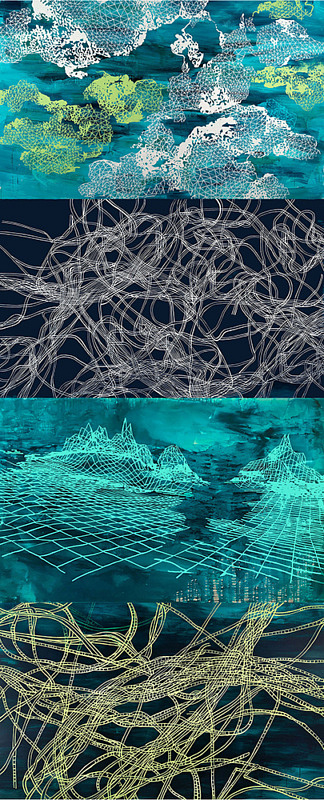

Two pieces on display at the Georgia Museum of Art were inspired by Joye’s research at the Guaymas Basin in the Gulf of California. “Progenitor Series” is a 22-foot-tall painting installation that utilizes data collected at sea, including sonar maps of hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor. The vertical orientation is inspired by the water column and Joye’s 2,200-meter descent.

“Shimmer,” a 64-foot-long steel sculpture, contains hexagonal sculptural forms and reactive LED lights that create patterns triggered by the viewer’s movement. Rutstein programmed the lights to mimic the siphonophore, a bioluminescent colonial organism that separates when disturbed, creating what looks like underwater fireworks.

She’s already working on another installation, one that will use temperature, light and sound to reflect the deep ocean.

“It’s going to create an experience for the public to get a sense of the sublime, of being there,” Rutstein says.

Joye and Rutstein met at a National Academies Keck Futures Initiative workshop on “Ocean Memory,” organized by a collaborative network of researchers from the sciences, arts and humanities.

“I have very rarely been part of a group that leaves me so inspired,” Joye says. “You’re challenged constantly to think beyond your boundaries.”

As Rutstein remembers it, Joye arrived a few minutes late and talked a mile a minute about a new animated project, showing a snippet of what would become “The Adventures of Zack and Molly.”

“In 5 minutes, I realized that she was one of the most ambitious, passionate, intelligent people I’ve ever met,” Rutstein says. “I was really drawn to her energy and her excitement for what she does.”

When they were talking later, Rutstein mentioned that she wanted to take a dive in the Alvin. Joye’s response was straightforward: “I’ll take you.”

“She said, ‘Are you serious?’” Joye remembers. “And I said, ‘Of course I’m serious. I’ll take you.’”

“I think I cried,” Rutstein says, and Joye laughs. “I was so happy. I couldn’t believe it.”

Her longtime dream came true—and a promise was fulfilled—last fall, when Rutstein took two dives in the Alvin. Joye and other scientists studied the unique environment in the Guaymas Basin, part of the Gulf of California, while Rutstein created art in a temporary studio in the main science lab on the R/V Atlantis.

The Gulf of California, also known as the Sea of Cortez, lies between two mountainous land masses, the Baja California Peninsula and the Mexican mainland. Multiple rivers pour into the gulf, loading it with sediment and nutrients. At the bottom is a “burst of the seam of the Earth,” as Joye describes it, where the San Andreas fault runs and fluids can reach 400 degrees. Such conditions—thick sediment loads over a hydrothermal center—speed up the natural processes that happen more slowly elsewhere, like the thermal cracking of organic matter to produce hydrocarbons and oil.

“It’s a place like no other,” Joye says. “It’s a geologically complex, dynamic system. You couldn’t find a better place to look at the intersection of deeply seated geological processes with microbiology and chemistry.”

Exploring the interaction between the geosphere and biosphere will help answer fundamental questions about the deep sea, a place where there are more unknowns than knowns.

A hydrothermal chimney colonized by Beggiatoa and Riftia pachyptila, or giant tube worms, at Cathedral Hill in the Guaymas Basin.

“It’s really easy to be disconnected from geology. We live on the land, but we don’t see the impact of geologic processes. It’s too slow,” Joye says. “In the deep ocean, it’s happening in front of your eyes. It’s fast. The fluids are belching out of the bottom, and you can see the heat. The water shimmers as these super-hot fluids are mixing with the cold bottom water.”

For Rutstein, who spent the year prior to the dives working with Joye on research related to the site, the journeys in the Alvin were unparalleled.

“It was a unique opportunity and window into the world of marine scientists, and I felt lucky to be there,” she says. “I tried to absorb as much as I could.”

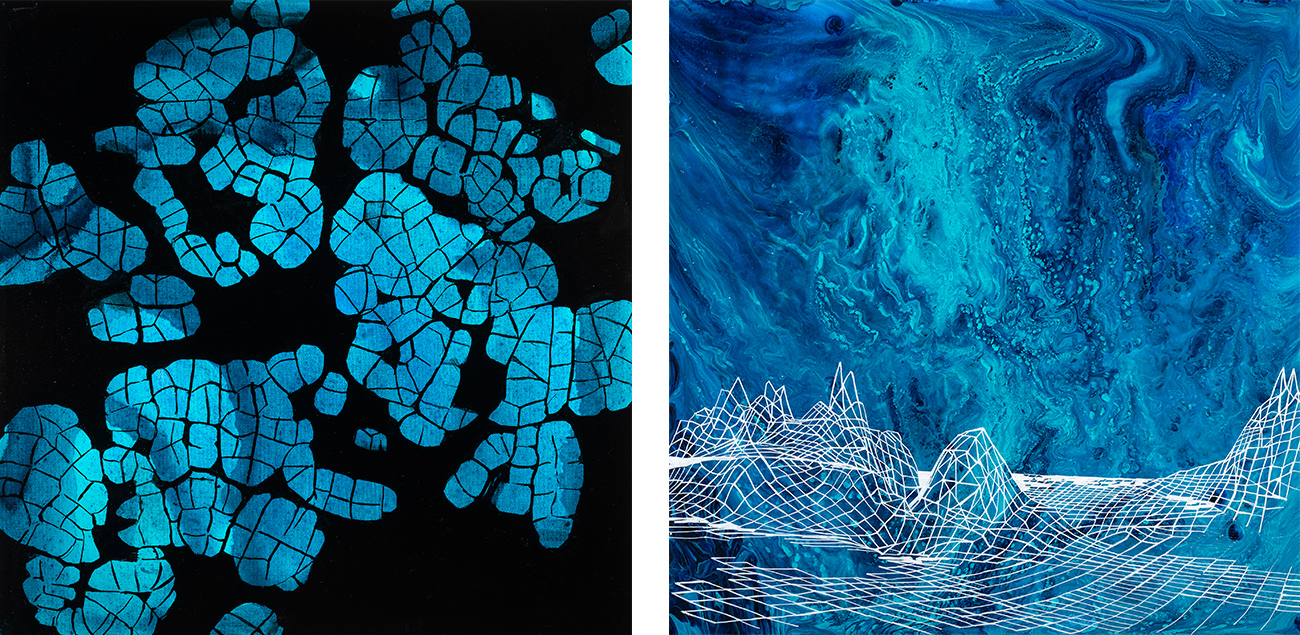

Rutstein took photomicroscopic images of the Beggiatoa bacteria that were collected, creating paintings inspired by the forms. She worked with sonar mapping data of the ocean floor. And she created paintings influenced by fluorescent microscopy of microbes. She had to keep things small on the ship, but she plans to make larger works, translating microscopic bacteria and microbial forms to a monumental scale.

“All of this has sparked a passion in me to shed light on these places and processes that are hidden from view,” she says. “There’s a sense of urgency to create a dialogue with the public about conservancy and environmental stewardship.”

In February, Joye went back to the Gulf of California to investigate two locations, the Delfin and Consag basins, that have never been explored. She didn’t know what she might find—perhaps new types of ecosystems or geological processes.

One thing she does know is that she will take more dives with Rutstein. Securing funding for an expedition takes about two years, and her next proposal will include the artist.

“I knew she would ‘see’ things I didn’t because she has a different frame of reference,” Joye says. “Experiencing the deep sea with her made me shift my reference point; it opened my eyes and generated a different experience.”

Joye believes that Rutstein’s art can create a similar experience for the public.

“It is an exceptional way to engage the public in what we do. Videos of the deep sea are beautiful, but they don’t initiate the conversation that a beautiful, spectacular sculpture would,” she says.

“Scientists have to start thinking about this broad context, and the connection with the humanities is essential. It’s something that most scientists really haven’t done enough of historically.”