Instead of searching for a needle in a haystack, what if you were able to sweep the entire haystack to one side, leaving only the needle behind? That’s the strategy researchers in the University of Georgia College of Engineering followed in developing a new microfluidic device that separates elusive circulating tumor cells (CTCs) from a sample of whole blood.

CTCs break away from cancerous tumors and flow through the bloodstream, potentially leading to new metastatic tumors. The isolation of CTCs from the blood provides a minimally invasive alternative for basic understanding, diagnosis and prognosis of metastatic cancer. But most studies are limited by technical challenges in capturing intact and viable CTCs with minimal contamination.

“A typical sample of 7 to 10 milliliters of blood may contain only a few CTCs,” said Leidong Mao, a professor in UGA’s School of Electrical and Computer Engineering and the project’s principal investigator. “They’re hiding in whole blood with millions of white blood cells. It’s a challenge to get our hands on enough CTCs so scientists can study them and understand them.”

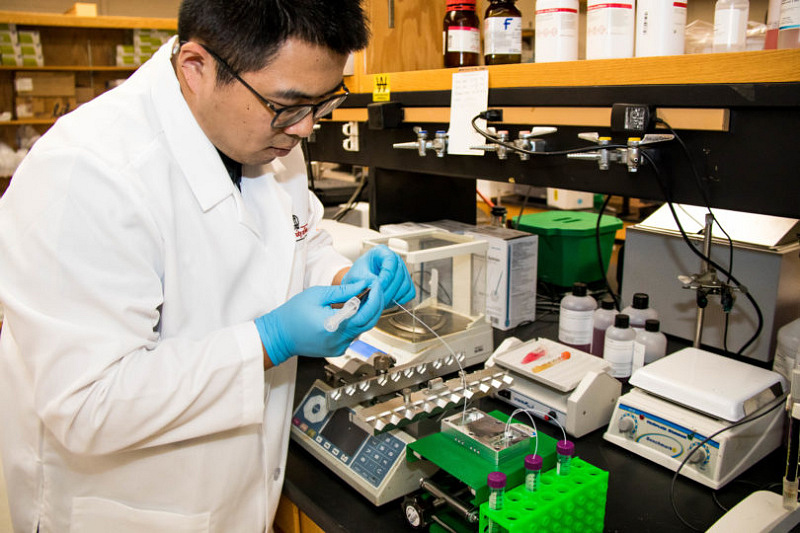

A blood sample streaming through the microfluidic device.

Circulating tumor cells are also difficult to isolate because within a sample of a few hundred CTCs, the individual cells may present many characteristics. Some resemble skin cells while others resemble muscle cells. They can also vary greatly in size.

“People often compare finding CTCs to finding a needle in a haystack,” said Mao. “But sometimes the needle isn’t even a needle.”

To more quickly and efficiently isolate these rare cells for analysis, Mao and his team have created a new microfluidic chip that captures nearly every CTC in a sample of blood—more than 99%—a considerably higher percentage than most existing technologies.

The team calls its novel approach to CTC detection “integrated ferrohydrodynamic cell separation,” or iFCS. They outline their findings in a study published in the Royal Society of Chemistry’s Lab on a Chip.

The new device could be “transformative” in the treatment of breast cancer, according to Melissa Davis, an assistant professor of cell and developmental biology at Weill Cornell Medicine and a collaborator on the project.

“Physicians can only treat what they can detect,” Davis said. “We often can’t detect certain subtypes of CTCs, but with the iFCS device we will capture all the subtypes of CTCs and even determine which subtypes are the most informative concerning relapse and disease progression.”

Davis believes the device may ultimately allow physicians to gauge a patient’s response to specific treatments much earlier than is currently possible.

While most efforts to capture circulating tumor cells focus on identifying and isolating the few CTCs lurking in a blood sample, the iFCS takes a completely different approach by eliminating everything in the sample that’s not a circulating tumor cell.

The device, about the size of a USB drive, works by funneling blood through channels smaller in diameter than a human hair. To prepare blood for analysis, the team adds micron-sized magnetic beads to the samples. The white blood cells in the sample attach themselves to these beads. As blood flows through the device, magnets on the top and bottom of the chip draw the white blood cells and their magnetic beads down a specific channel while the circulating tumor cells continue into another channel.

The device combines three steps in one microfluidic chip, another advance over existing technologies that require separate devices for various steps in the process.

“The first step is a filter that removes large debris in the blood,” said Yang Liu, a doctoral student in UGA’s department of chemistry and the paper’s co-lead author. “The second part depletes extra magnetic beads and the majority of the white blood cells. The third part is designed to focus remaining white blood cells to the middle of the channel and to push CTCs to the side walls.”

Wujun Zhao is the paper’s other lead author. Zhao, a postdoctoral scholar at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, worked on the project while completing his doctorate in chemistry at UGA.

“The success of our integrated device is that it has the capability to enrich almost all CTCs regardless of their size profile or antigen expression,” said Zhao. “Our findings have the potential to provide the cancer research community with key information that may be missed by current protein-based or size-based enrichment technologies.”

The researchers say their next steps include automating the iFCS and making it more user-friendly for clinical settings. They also need to put the device through its paces in patient trials. Mao and his colleagues hope additional collaborators will join them and lend their expertise to the project.

In addition to Weill Cornell Medicine, researchers and physicians at the Henry Ford Health System in Detroit, University Cancer and Blood Center in Athens, and UGA’s Clinical and Translational Research Unit served as clinical collaborators on the project. The team also included researchers from the UGA College of Veterinary Medicine, the Augusta University-University of Georgia Medical Partnership, and UGA’s department of genetics.

The project was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health.