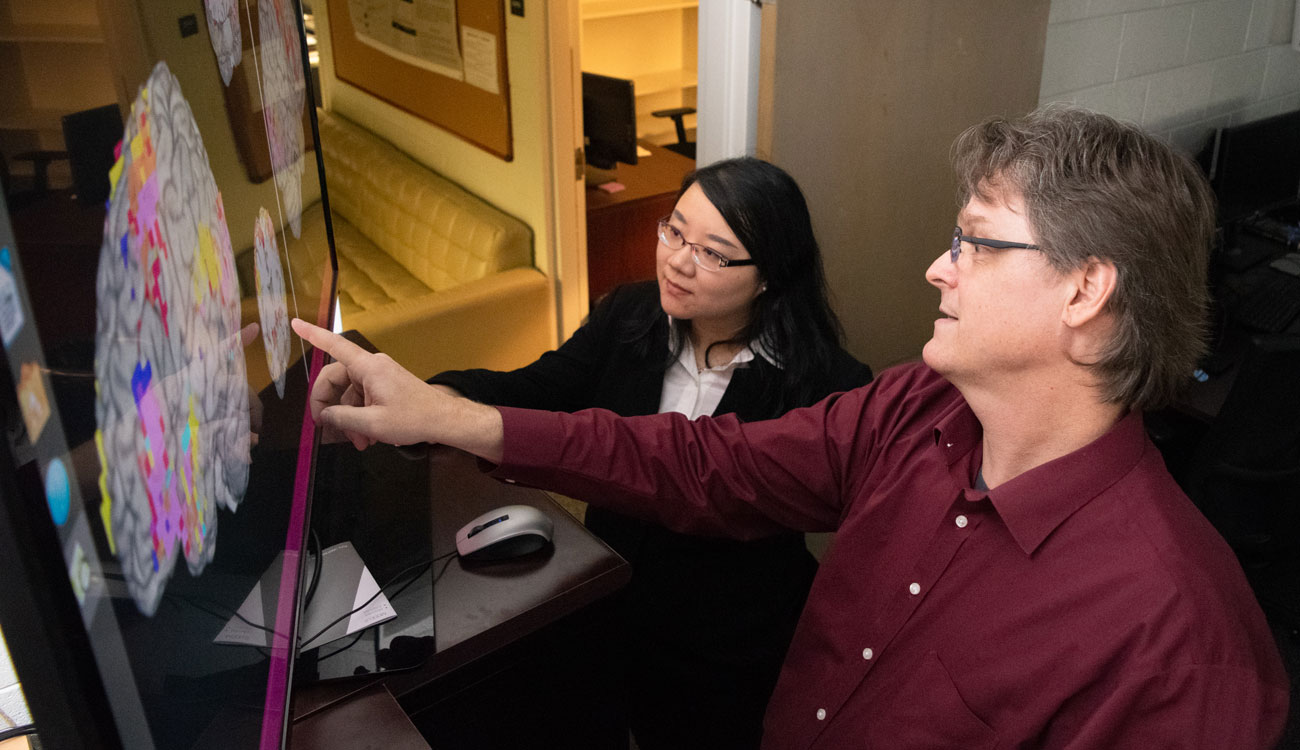

Last year, the Food and Drug Administration declared that youth vaping had reached epidemic status. By Nov. 5 of this year, 2,051 lung injuries—and 39 deaths—related to vaping had been identified by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Some states have taken action, restricting who can sell vaping products and enacting bans on flavored products. There’s little scientific data to guide these efforts, but UGA’s Jiaying Liu and Lawrence Sweet, both in the Franklin College of Arts and Sciences, are working to change that.

Liu, assistant professor of communication studies, and Sweet, professor of psychology and director of the Clinical Neuroscience Laboratory, have teamed up to investigate vaping among young adults. Liu secured internal grant funding through the Office of Research, and they conducted a pilot study over the summer, collecting data used to apply for support for a more comprehensive study.

In the past few months, there have been numerous stories about the dangers of vaping, but some say that e-cigarettes can help smokers quit. What’s your take?

Jiaying Liu: E-cigarettes are the most commonly used tobacco product among youths and young adults. In 2011, the use of e-cigarette products was only 1.5% among youths. In 2018, it was more than 20%. This is very alarming. We know tobacco use has been declining for several years because of very effective tobacco-control efforts. Some people think e-cigarettes are a harm-reduction product because they don’t burn the tobacco, so there’s no tar and, in theory, no carcinogen to lead to cancer.

Lawrence Sweet: Others think e-cigarette use could be a gateway device that will cause nicotine addiction and dependence that ultimately lead to trying cigarettes and, long term, actually re-normalize smoking in our society.

Liu: We found several studies that confirmed that for every one adult smoker who quits smoking with the use of e-cigarettes, there are 81 never smokers—youths or young adults—who actually initiate smoking after e-cigarette use.

Flavored e-cigarette juice has gotten a lot of attention. One company suspended sales of its fruit-flavored e-juice after the Trump administration announced a policy that is expected to remove all flavored e-cigarettes from the market. Why are flavors an issue?

Liu: When people start with cigarettes, they often stop at the experimentation stage because the nicotine tastes bitter. With e-cigarettes, the flavors can mask the unpleasant nicotine flavor.

Sweet: Until they’re hooked.

Liu: Until they’re hooked, and they feel like they need more nicotine and can handle the harsher experience of smoking cigarettes.

Sweet: It’s like training wheels for cigarettes.

Liu: Yes. Exactly.

How will your research address these issues?

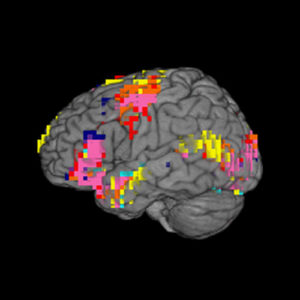

Liu: We’re finding out whether we can use neuroimaging methods to better predict transitioning from e-cigarette usage to smoking cigarettes. If we can find sensitive and accurate neural markers to predict who is going to transition to smoking and who is not, we can plan better prevention and treatment efforts.

Sweet: There’s been a lot of research about whether people will succeed or fail in smoking or drug use cessation using functional MRI (fMRI) markers as predictors. We’re proposing the opposite: Can we use these same markers to predict who will start smoking?

Liu: Larry has studied similar neural markers and has successfully predicted smoking relapse among former smokers. We wanted to see if similar types of neural mechanisms will also predict which e-cigarette users will transition to smoking cigarettes.

Sweet: We’re looking above and beyond the predictors we already know—for example, early-life stress, parents who smoke—to find a higher predictive validity, one that may involve underlying, unconscious mechanisms that users can’t accurately self-report.

What was the focus of the pilot study you conducted this summer?

Liu: We worked with participants who are heavy e-cigarette users but nonsmokers: young adults who had vaped more than 20 days, but not smoked any cigarettes, during the previous 30 days. These are the people most likely to transition from e-cigarettes to cigarettes.

Sweet: We collected neuroimaging data via fMRI scanning, as well as pre- and post-scan surveys. During the scanning session, they were shown three types of pictures created by Jiaying: images of e-cigarette devices or cigarettes; images of e-juice packaging that were plain or featured vivid fruit or candy themes; and educational campaign messages about the dangers of vaping.

Liu: Cigarettes have very strict packaging regulations, but that’s not true for e-cigarettes. Many feature pictures of fruit and candy that are alluring to youths. They are intentionally making their packaging look like a juice box, or chocolate-covered biscuit sticks, things like that. It’s classic associative learning—nicotine and food can reinforce each other to make people more likely to become addicted to nicotine.

Sweet: One question we wanted to explore is whether packaging can make people more likely to crave e-cigarettes and cigarettes. Associative learning would say yes—if you’re using mango-flavored e-cigarettes, in the future you will be susceptible to every mango visual. Mangoes in the grocery store will make you crave e-cigarettes and potentially cigarettes.

Liu: We also examined the effectiveness of different educational campaign messages using different themes, for example, emotional appeals like guilt regarding secondhand vapor. We are finding out whether neuroimaging data collected during exposure to these messages can predict a reduction in participants’ intention to continue using e-cigarettes. If it can, we’ll be able to pinpoint the most effective type of messaging that agencies like the FDA could use for public education campaigns.

What did you learn, and what did the participants learn?

Liu: We found that the participants actually were educated by our campaign messaging. Many began vaping with flavors that they didn’t consider harmful based on the packaging: “It looked like apple juice.” They also didn’t know that one vaping cartridge equals one pack of cigarettes, so they’re now better able to monitor how much they’re using. Our preliminary neuroimaging results also showed that emotional appeals seem to be most effective, compared to cognitive and social appeals, in reducing their e-cigarette use escalation.

Sweet: The participants seemed to be unaware that there are chemicals in the vaping liquid. It’s called vapor, so they think it’s water, when in fact there can be chemicals present that are not disclosed because e-cigarette makers are not required to list ingredients. For example, there’s scientific evidence that flavored vaping juice contains diacetyl, which causes popcorn lung.

Liu: The good news is that we followed up with participants four weeks after the fMRI data collection, and they’re very interested in knowing our results. We hope that this study—and the one we’re conducting this semester, which is similar—will provide data that can guide regulatory and educational efforts at the national level. But we also hope that the study experience will help our participants lower their rate of transitioning to cigarettes.