Scientists have reconstructed the tree of life for all major lineages of perching birds, also known as passerines, a large and diverse group of more than 6,000 species that includes familiar birds like cardinals, warblers, jays and sparrows.

The study, published April 3 in PNAS, is the most comprehensive work to date on passerine evolution.

Researchers at Louisiana State University, the University of Georgia and 25 institutions from around the world accomplished the massive project using samples from 221 bird specimens from 48 countries.

Using these samples, they extracted and sequenced thousands of pieces of DNA representing all passerine families, and they used these sequence data to understand how passerine species are related to study when and how passerines diversified in relation to Earth’s history.

“By sequencing DNA from these invaluable specimens using new technologies, we can begin to understand how species evolved over the course of millions of years at a resolution that is unprecedented,” said co-author Brant Faircloth, an assistant professor in the LSU Department of Biological Sciences and alumnus of UGA.

This project has been 10 years in the making, said co-author Travis Glenn, an associate professor of environmental health science at the UGA College of Public Health.

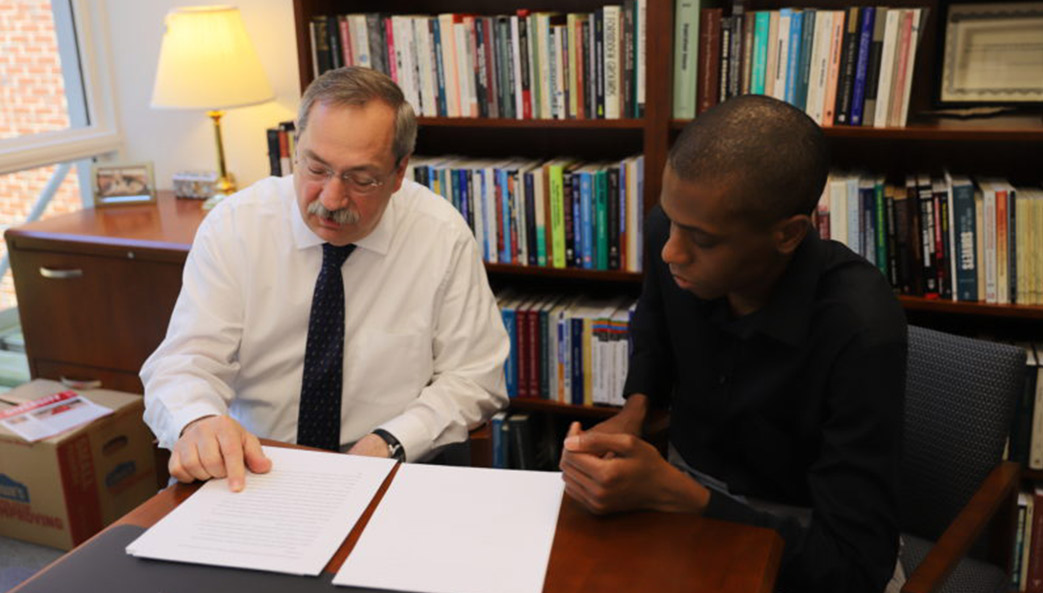

Glenn and Faircloth began developing the DNA technology used in the current study when Faircloth was a doctoral student at UGA. The tools they developed enabled them to answer longstanding questions about the evolution of various bird species.

“Passerines are the most species-diverse group of birds,” said Glenn, “and that diversity has happened relatively recently in evolutionary time. We want to know how and why they were able to diversify so rapidly.”

The unique benefit of this DNA technology, said Glenn, is not only does it make it feasible to use the same set of genetic markers for studies on thousands of species, but it also allows scientists to compare genomes across species.

“It’s a way of pulling out repeatable portions of a genome. When you’re doing comparisons among different species, you will have chunks of DNA that you can line up, so that you’re comparing apples to apples,” he said.

Scientists can employ the methods used here to identify unknown members of any species, including bacteria, said Glenn, who is now leveraging these DNA tools in studies ranging from bacterial communities in health care settings to ticks and tick-borne diseases.