Most of us have suffered the indignity of food poisoning at some point in our lives. Perhaps you got yours at an unfamiliar roadside diner, or maybe you happened upon a potato salad of questionable provenance at a weekend potluck. Regardless of the source, you may take some consolation in knowing that you did not suffer alone.

In the U.S., about 48 million—or roughly one in six people—fall victim to some form of foodborne illness every year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The overwhelming majority of those affected will weather the gastrointestinal storm and return to work or school after a few uncomfortable days. But foodborne illness can be serious.

Among the millions of people sickened every year, 128,000 must be hospitalized and about 3,000 die. Foodborne illnesses also impose a tremendous economic burden of more than $15.5 billion in treatment costs and lost wages every year, according to the most recent data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

These numbers are a stark reminder that while we have made great advances in food safety, there is always ample room for improvement. Few people are as aware of this as Michael Doyle. The Regents Professor of Food Microbiology and founding director of UGA’s Center for Food Safety, Doyle has spent the better part of 30 years studying the pathogens that make us sick.

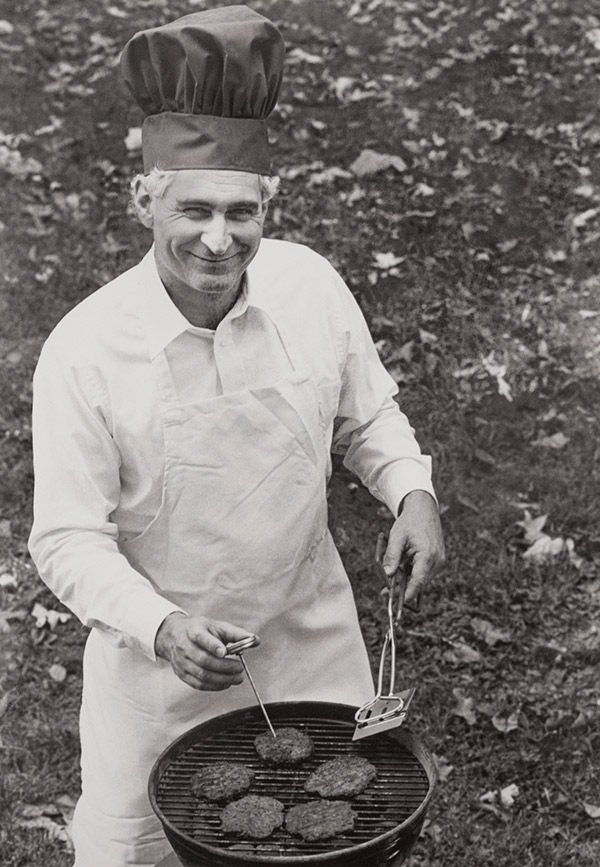

“I grew up on a dairy farm in Wisconsin, so I appreciated the importance of safe food from a very young age,” Doyle said. “I’ve carried those lessons with me all the way to UGA, where my colleagues in the Center for Food Safety and I work to develop new ways of detecting and controlling the harmful microbes in food that can make people sick.”

A changing landscape

Doyle’s scientific career began in earnest at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where he earned a Bachelor of Science in bacteriology, and a Master of Science and Ph.D. in food microbiology. He worked as a faculty member in UW’s Food Research Institute from 1980 to 1991, and he gained wide recognition for developing the first test to detect E. coli 0157, a bacterial food pathogen that can cause diarrhea, abdominal cramps, kidney failure and even death.

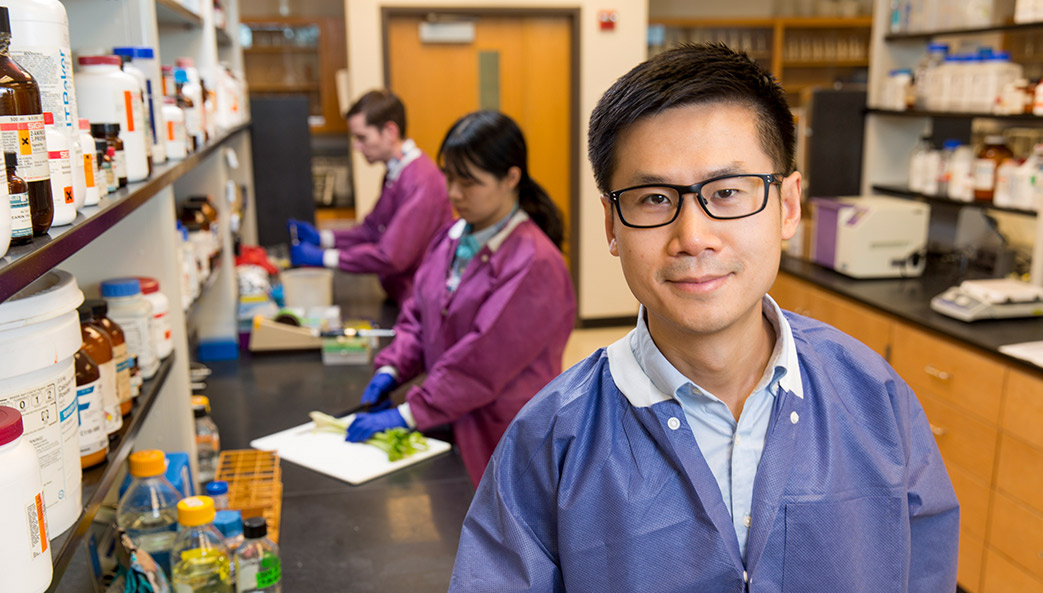

He came to UGA in 1991 to lead the newly developed Center for Food Safety, which is now home to 19 faculty. He also began working with scientists at the CDC, who came to rely on Doyle’s counsel and skill in the laboratory when faced with a new outbreak of foodborne illnesses.

Over the course of his career, Doyle has seen dramatic changes in the way food companies and regulatory agencies manage the nation’s food supply. He’s watched household brands take a beating in the news media when one of their products is connected with an outbreak, and he and his colleagues have helped create a myriad of new scientific tools to help those companies improve their operations.

“Many companies in years gone by talked a lot about food safety, but they didn’t really spend a lot of money on it,” said Doyle. “But the world has changed in the last few years, and people are becoming more serious about food safety culture.”

Doyle has forged strong working relationships in the food industry, which has allowed him to mold the Center for Food Safety into a program that develops real solutions for companies that are committed to producing safer foods.

“Today it is largely companies that are paving the way in terms of developing more advanced methods to isolate harmful microbes,” he said. “Big brands like Kraft and General Mills can’t afford to have food safety hiccups. Also, the Department of Justice prosecutes these cases more aggressively now than they have in the past, so there is a financial incentive to produce safe products.”

When dangerous pathogens do slip through the cracks, scientists may call upon a host of new genetic tools to track the outbreak. Researchers at the CDC and other agencies can isolate pathogens from tainted food, analyze their unique genetic makeup and store that information in databases.

“When a patient comes in complaining of food poisoning, they can compare the pathogen taken from that patient with the database to see if there might be links to isolates that have come from food processing facilities,” said Doyle, who is also a member of the National Academy of Medicine. “They can even go back in time and look at microbes that caused outbreaks years ago to see if there is any connection to something happening today. It’s incredible; the technology is driving the industry in new directions very quickly.”

But detection is only one part of the equation. There is a major push in the food industry not only to identify potentially harmful pathogens, but also to eliminate them or control their spread, he said.

To help solve this problem, Doyle, along with Tong Zhao, an assistant research scientist at UGA, invented a food wash that significantly reduces the risk of foodborne illnesses by killing harmful microbes before they reach the supermarket or dinner table. Known by the trade name FIT-L, the wash has been successfully tested against more than 30 different harmful microbes, including E. coli, Salmonella and Yersinia pestis, the bacterium that causes plague.

“We’ve tested a lot of different types of washes and treatments that are out there, and quite honestly, this is one of the best that we’ve come across,” said Doyle, who was the first UGA faculty member to be named a fellow of the National Academy of Inventors.

Life beyond the lab

Doyle stepped down from his position as director of the Center for Food Safety this year after 25 years at its helm. He will be replaced by Francisco Diez Gonzalez, who joined UGA after working as a faculty member and head of the Department of Food Science and Nutrition at the University of Minnesota.

“I can’t even imagine walking into the door without his help,” Diez said. “Close working relationships like the ones Mike has built require a lot of trust, and they are critical for the future success of the center.”

Doyle will remain at UGA for a year to help Diez make the transition, but he’s looking forward to some well-deserved time off.

“Our immediate family has grown from five to 14 with all my grandkids and my children’s spouses, and it’s continuing to grow,” he said. “I’d like to see more of them.

“I’ll try to continue working with companies that really want to raise the bar on food safety, but the Center is in good hands with Francisco, and I’m looking forward to spending more time with family.”