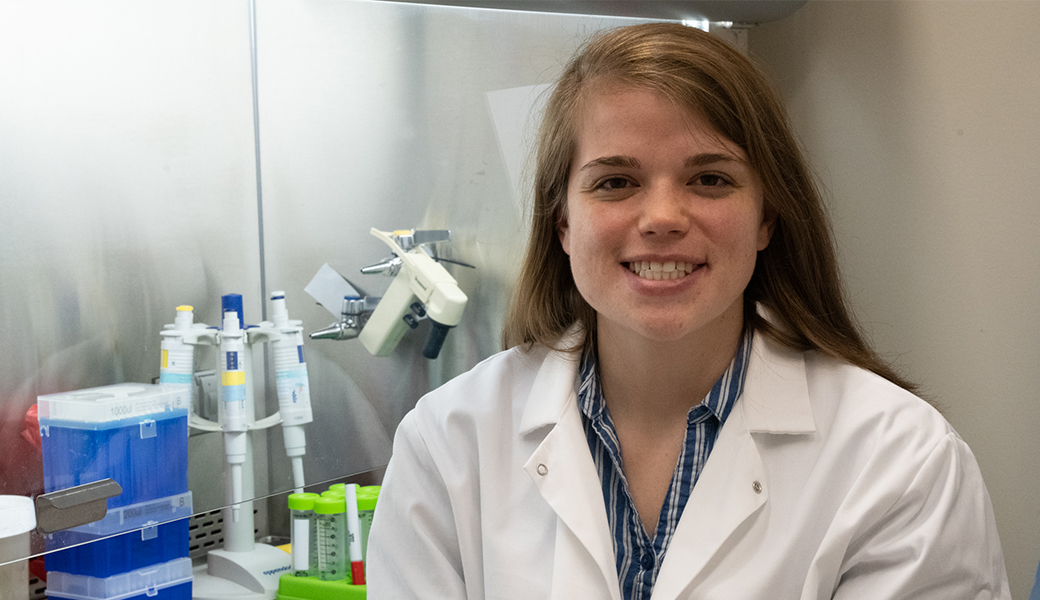

Cassie Russell, a graduate student in the Department of Infectious Diseases, was an undergraduate when she first heard of Naegleria fowleri, also known as the brain-eating amoeba. While whole lectures in her parasitology course had been dedicated to other parasites, N. fowleri was barely a mention.

“I remember maybe 15 minutes was spent on it,” said Russell. “I was shocked that was all that was known about this deadly organism.”

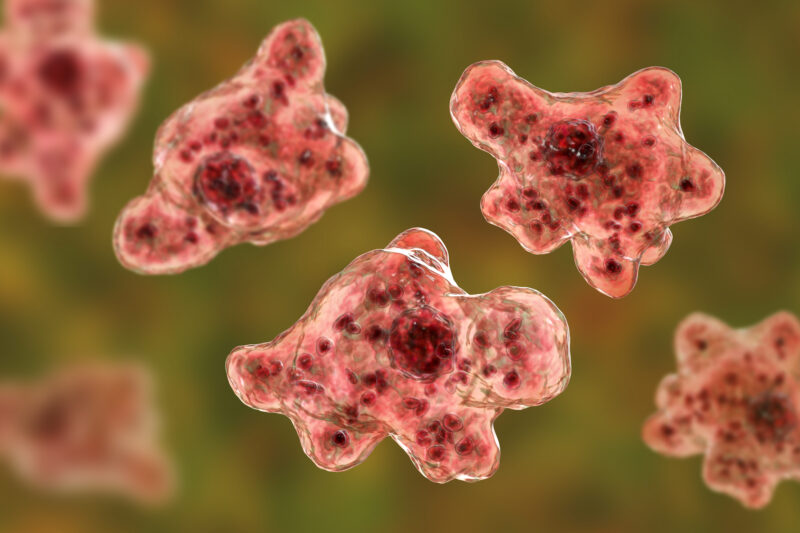

N. fowleri causes the acute neurological disease primary amoebic meningoencephalitis (PAM). There have been hundreds of reported cases of PAM, but only seven survivors worldwide, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

After arriving at UGA, Russell was pleased to find out that N. fowleri was one of the parasites being studied in Dennis Kyle’s laboratory at the Center for Tropical and Emerging Global Diseases.

“I had the opportunity to speak with families in Florida who had lost someone to Naegleria fowleri infection,” she said. “The fear they had in not knowing what was wrong with their loved one and then learning that there was very little that could be done—their stories were just heartbreaking.”

Individuals, most commonly young children, become infected when they inhale warm freshwater contaminated with N. fowleri. This typically occurs during the late summer months when people are participating in recreational activities in rivers and lakes, but it can also occur when people use unsterilized tap water in nasal irrigation devices. It is more likely to occur in the southern United States, but infection is very rare. Between 2011 and 2020 only 33 cases were reported in the United States, according the CDC.

N. fowleri is one of the most neglected of the neglected tropical diseases. However, knowledge about the parasite has been growing since the 1960s as scientists build on new data and apply new technology. Russell is doing her part and was the lead on a study recently published in Microbiology Spectrum where, for the first time, drug susceptibility was tested across 11 clinical isolates.

“Current drug treatment is a cocktail of six different drugs,” said Russell. “However, only a few isolates have been tested in the lab for susceptibility. We don’t know if some drugs work better for different strains.”

A big question facing researchers is why these drugs show effectiveness in the lab when so few real-world cases have been successfully treated. Russell suspected that other factors were at play in treatment failure, such as genetic differences among geographically distinct amoeba populations.

The 11 isolates used in the study came from patients who contracted N. fowleri in different geographic regions. Russell found that these isolates had significant differences in susceptibility to seven of the eight drugs currently used to treat the infection.

The need for effective and fast-acting treatments is especially great. PAM is almost always fatal, with death occurring about a week after the initial onset of symptoms.

Doctors are racing against the clock as there is often a delay in diagnosis: The symptoms mimic meningitis, and N. fowleri is a rare infection. The drugs used can also be pretty toxic, so identifying the safest and most effective drug treatment could significantly improve outcomes.

Russell’s findings are another stepping stone to propel N. fowleri research toward increased understanding of this parasite and ultimately better treatments. For example, she realized that there is not a gold standard for genotyping.

“Researchers could be talking about genetically different isolates but not realize it,” said Russell.

In addition to creating a genotyping standard, she has identified combinational drug studies to test for synergism as a next step. For now, though, Russell is focusing on another need in the fight against N. fowleri—diagnostics.

“Awareness, improved diagnostic techniques and faster-acting drugs are needed to improve outcomes,” she said.