Lohitash Karumbaiah ended his summer by making history, as a member of the first research team to ever simulate recovery from a traumatic brain injury in a petri dish.

For Karumbaiah, the breakthrough to help heal brain injuries was the result of years of working to understand nervous system injuries.

With his diverse influences from having worked in industry and academia, Karumbaiah approaches research with a holistic curiosity that has allowed him to bridge many disciplines and learn from a diverse set of mentors.

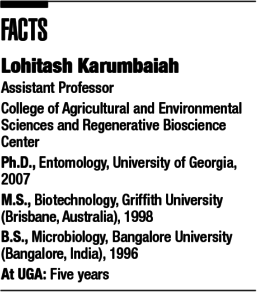

Since 2013, Karumbaiah has served as an assistant professor in the animal and dairy science department of UGA’s College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences and the university’s Regenerative Bioscience Center.

Since 2013, Karumbaiah has served as an assistant professor in the animal and dairy science department of UGA’s College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences and the university’s Regenerative Bioscience Center.

He wants the students and younger scientists he works with to know the importance of an open mind and the ability to chart one’s own path, even in the sometimes-siloed halls of academia.

“Sometimes it takes students a long time to find their passion—just like it did for me,” Karumbaiah said. “But if you enjoy what you do, it’s really a good place to start. And if you do that and are continuously pushing the envelope then eventually you find your passion, I think. That’s been my experience.”

Although he’s always worked in biochemistry in some form or fashion, Karumbaiah set his sights on neuroscience and neural tissue engineering upon completing his doctoral thesis under the direction of Michael J. Adang, a professor of biochemistry and molecular biology and entomology at UGA. He spent his postdoc years as senior research scientist with Ravi V. Bellamkonda in the Neurological Biomaterials and Cancer Therapeutics Laboratory in the biomedical engineering department at the Georgia Institute of Technology.

“My worldview kind of evolved after I finished my Ph.D.,” Karumbaiah said. “I enjoyed my Ph.D. work but wanted to conduct postdoctoral research in the biomedical sciences where my work could have a greater impact.”

With the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention statistics stating that 30 percent of all injury-related deaths in the U.S. are caused by traumatic brain injuries and thousands more surviving with physical and mental impairments or emotional changes, working on brain repair seemed like a good place to make an impact.

Before this summer’s simulation of repaired brain functions in his lab in the RBC, Karumbaiah was part of a team that developed a substance called “brain glue.”

The gel medium was created using what researchers have learned about the role of carbohydrates in the brain and the way their composition changes around damaged areas of the brain.

The “glue” was able to act as a substrate to safely transplant neural stem cells and provide the chemistry and conditions needed to protect the brain and improve neuronal function.

That second part came closer to fruition in the famed petri dish late this summer. The next step is to work with animal models to integrate these two approaches, and if successful, to use this to help repair brain injuries in an actual patient.

Even for Karumbaiah, who has been working in neuroscience for the last decade, the pace of progress surrounding brain regeneration has been amazing.

“This is the cutting edge of biomedical science,” he said of the entire field of brain research. “I think the focus on the brain is a lot more now than it has ever been. President Obama’s BRAIN Initiative and a number of programs that have been set up to fund this type of research are a testament to this.”

The other factor that has contributed to advances is a new sense of collaboration. The Regenerative Bioscience Center, where Karumbaiah’s research is housed, was created to promote cross-discipline and multi-institutional biomedical research within the Georgia Research Alliance with the Georgia Institute of Technology, Georgia State University, the Medical College of Georgia and Emory University.

“This is a great place to be. It’s a good combination of basic science, excellent engineering and a top notch medical school within 60 or 70 miles of each other,” he said. “It is just fabulous … this combination of things just worked out for me organically.”